What the banks’ three-year war on Dodd-Frank looks like

Graphics by Ben Chartoff and Amy Cesal. Network analysis by Alexander Furnas.

In the three years since President Barack Obama signed the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, federal regulators charged with implementing it have opened their doors to the biggest banks over and over again – 14 times as frequently as they have to representatives of consumer and pro-financial reform groups, a new Sunlight Foundation analysis finds.

By most accounts, the banks’ besiege-the-regulators strategy has yielded rich rewards in sapping, slowing, and stymieing regulations intended to prevent another massive financial crisis. The emerging consensus is that Dodd-Frank implementation is limping, while the big banks are poised to return to being the most profitable industry in the U.S.

CASE STUDY: How ex post facto lobbying softens regs

Sunlight’s analysis is based on logs of Dodd-Frank meetings at the Commodities Futures Trading Commission, the Treasury, and the Federal Reserve Board, available through Sunlight’s Dodd-Frank Meetings Tracker. Because of problems with data quality and comprehensiveness, we had to exclude two other regulatory agencies (the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Deposit Insurance Commission). And because of the time involved in data cleaning, we also excluded 22 percent of reported meetings – those that did not include “active” players. (By “active” we mean organizations that showed up at least five times in meeting logs.) For more on the data, see our methodology section at the end of this post, and read our companion piece, “Dodd-Frank meeting data need improvement.”

Still, the imbalances our analysis reveals are so overwhelming that we can be confident that they are not merely a feature of the reporting practices.

Figure 1 visualizes all “active” organizations and their cumulative meetings, from June 2010 to June 2013. Mouse over the dots to see which organizations they represent. Drag the slider on the bottom to see how the cumulative totals change over time.

Figure 1.

Dodd-Frank Meetings by Organization

This graphic shows the cumulative total meetings organizations attended at the CFTC, Treasury, and Fed on Dodd-Frank issues from July 2010-June 2013. To see the name and meeting count of an organization, mouse over its circle. Use the slider at the bottom to view the data at a given point in time.

Goldman Sachs is the most active organization. It had representatives at 222 meetings, covering 51 topics. JP Morgan participated in 207 meetings, also covering 51 topics. Combined, these two Wall Street giants alone participated in 50 percent more meetings (429) than the top 20 most active pro-reform groups combined (287).

Rounding out the top five are Morgan Stanley (175 meetings, covering 46 topics), Bank of America (156 meetings, covering 41 topics) and Citigroup (134 meetings, covering 47 topics).

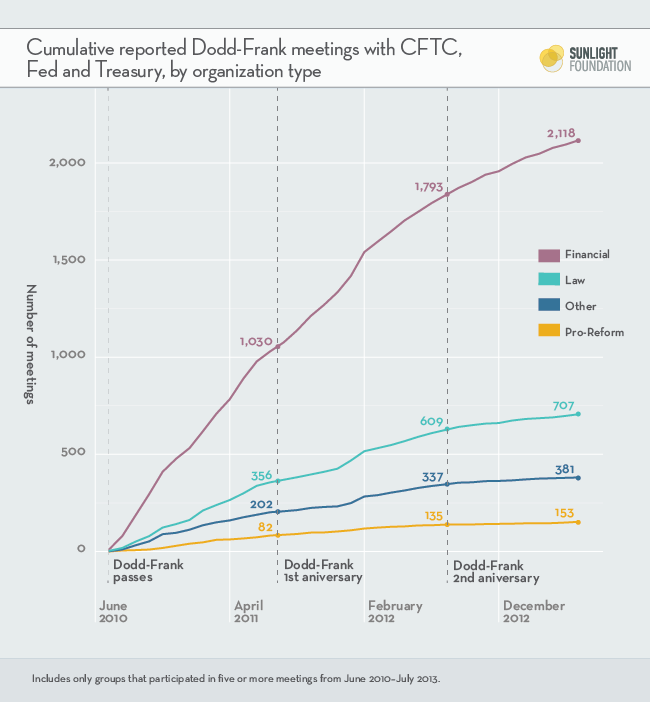

All told, active financial institutions show up in the meetings logs for at least 2,118 meetings during the first three years of implementation. In the 152 weeks our data cover, we find 59 weeks in which regulators met with financial sector representatives at least once every single day (Monday through Friday), and 47 weeks in which they met with financial sector representatives at least four times. Only three weeks (two Christmas break weeks, and one August congressional recess) show no meetings with the financial industry.

By contrast, active pro-reform groups appeared in only 153 meetings logs – only about one meeting for every 14 regulators held with financial institutions and associations.

Moreover, 24.2 percent of pro-reform group meetings took place on a single issue: the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. On non-CFPB issues, the ratio jumps to 2,016 meetings for financial institutions and 116 meetings for pro-reform groups: a ratio just over 17-to-1.

Law and lobbying firms, largely working in service of financial institutions, appeared in 707 meetings. Other, non-financial corporate interests, largely energy and agricultural companies, participated in 381 meetings. These companies are major purchasers of derivative contracts, which they use to hedge against price risk.

Figure 2 plots the cumulative trends of the four different types of organizations since the passage of Dodd-Frank, clearly illustrating the striking disparities in participation.

Figure 2.

Top Participants

Table 1 (below) lists the most active participants. When we arrange organizations by number of total meetings, 21 of the top 25 are financial institutions or financial trade groups. The only exceptions are one government affairs organization (Delta Strategy, which was founded by former CFTC chairman James Newsome, at No. 7, 100 meetings), and three prominent law firms: Sullivan & Cromwell at No. 17, with 73 meetings, and Davis, Polk & Wardwell and Skadden Arps, both tied at No. 24 with 54 meetings.

It’s not until we get to No. 32 on the list that we find our first pro-reform group, Americans for Financial Reform, which represents a coalition of consumer and labor organizations, with 43 total meetings, tied with law firm Patton Boggs.

Table 1. Organizations with the most meetings

| Organization | Total meetings | Total topics | Solo meetings | Top issue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goldman Sachs | 222 | 51 | 71 | Derivatives Markets And Products |

| JPMorgan Chase & Co | 207 | 51 | 67 | Volcker Rule |

| Morgan Stanley | 175 | 46 | 60 | Derivatives Markets And Products |

| Bank of America | 156 | 41 | 36 | Derivatives Markets And Products |

| Citigroup Inc | 134 | 47 | 24 | Derivatives Markets And Products |

| Barclays | 115 | 45 | 44 | Derivatives Markets And Products |

| Delta Strategy | 100 | 28 | 26 | Xxvi. Position Limits |

| Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association | 97 | 36 | 22 | Xiii. Sef Registration |

| Wells Fargo | 94 | 29 | 16 | Derivatives Markets And Products |

| Deutsche Bank AG | 92 | 46 | 10 | Derivatives Markets And Products |

| BlackRock Inc | 87 | 35 | 48 | Vi. Segregation And Bankruptcy |

| UBS Ag | 82 | 42 | 21 | Derivatives Markets And Products |

| Credit Suisse Group | 80 | 45 | 16 | Volcker Rule |

| Bank of New York Mellon | 79 | 32 | 8 | Derivatives Markets And Products |

| State Street | 78 | 33 | 16 | Derivatives Markets And Products |

| CME Group | 73 | 24 | 55 | Xxvi. Position Limits |

| Sullivan & Cromwell | 73 | 31 | 21 | Volcker Rule |

| American Bankers Assn | 65 | 29 | 29 | CFPB |

| Icap | 64 | 17 | 37 | Xiii. Sef Registration |

| HSBC | 63 | 34 | 8 | Derivatives Markets And Products |

| Fidelity Investments | 61 | 30 | 10 | Ii. Definitions |

| Managed Funds Assn | 56 | 29 | 9 | Xxvi. Position Limits |

| Davis, Polk & Wardwell | 54 | 25 | 9 | Volcker Rule |

| Skadden Arps | 54 | 26 | 16 | Iii. Business Conduct Standards W/ Counterparties |

| Chatham Financial | 51 | 14 | 16 | Xi. End-user Exception |

| ISDA | 51 | 24 | 15 | Xiii. Sef Registration |

| PIMCO Funds | 49 | 22 | 9 | Xiii. Sef Registration |

| Citadel | 48 | 22 | 9 | Vii. DCO Core Principles |

| US Chamber of Commerce | 47 | 27 | 14 | Xi. End-user Exception |

| Americans for Financial Reform | 43 | 29 | 16 | CFPB |

| US Bank | 43 | 25 | 7 | CFPB |

| Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton | 43 | 23 | 4 | Cross-border |

| Patton Boggs LLP | 43 | 23 | 7 | Xiii. Sef Registration |

For data on all groups with at least five meetings, click here.

Meetings by Agency

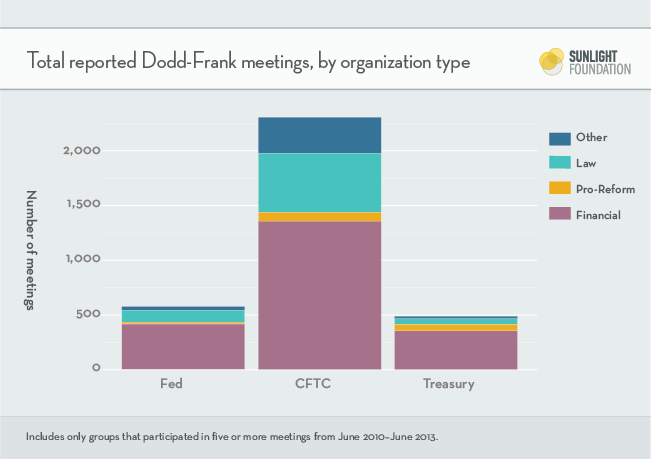

While Figures 1 and 2 (above) gave us a good sense of the diverging trends over time, Figure 3 below looks at the cumulative breakdowns by agency. The figure is pretty self-explanatory.

Financial sector companies and organizations were present at :

- 90 percent of meetings at the Fed;

- 82.7 percent of meetings at the Treasury; and

- 74.8 percent of meetings at the CFTC.

By contrast, pro-reform groups were present at:

- 3.3 percent of meetings at the Fed;

- 13.7 percent of meetings at the Treasury; and

- 4.4 percent of meetings at the CFTC.

It’s also worth noting that the majority of the Treasury meetings with pro-reform groups (60.3 percent) focused on a single issue: the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), the new watchdog agency mandated by Dodd-Frank.

Figure 3.

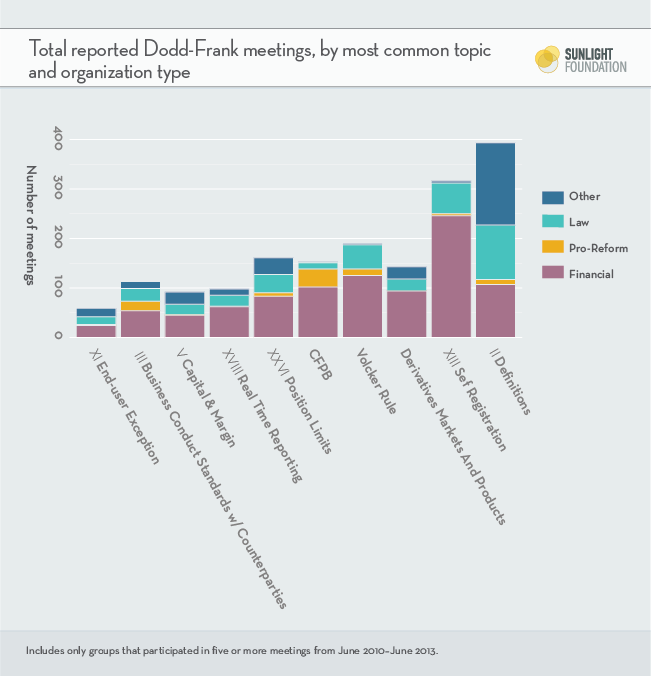

Figure 4 breaks out the imbalances by then ten most common topics mentioned in the meetings log records. (Again, we are relying on what the agencies themselves report. And while we’ve done some cleaning of the topic titles, there is no standard set of distinct topic codes.)

Figure 4.

To download summary data on all topics by organization types, click here.

Caveats aside, a few notable trends are worth highlighting. Of the ten topics, reform-oriented groups reach the peak of their participation on the implementation of the CFPB, being present for 26 percent of the 137 meetings on the topic. They are also present at 16 percent of the meetings on Business Conduct Standards.

Beyond those topics, pro-reform groups’ participation is rare. They were present for about nine percent of the meetings on the Volcker Rule, and just four percent of the meetings on Position Limits, and after that about one percent of the meetings on everything else. There was not a single pro-reform group meeting reported on the topic of Derivatives Markets and Products.

With the exception of the CFPB, the Volcker Rule and Derivatives Markets and Products, lawyers and lobbyists show up consistently at between 17 and 22 percent of the meetings. Depending on who is affected, the share of corporations from the financial sector fluctuates from a low of 27 percent (End-user Exception, which is primarily of interest to energy and agricultural companies) to a high of 93 percent (on Derivatives).

Given the determined participation by financial firms on derivatives, it is hardly surprising that the CFTC and SEC caved into industry pressure and raised the derivatives regulatory oversight threshold from $100 million (as originally proposed) to $8 billion – an increase of 80 times, and a change that exempted 85 percent of companies that would have been covered under the original threshold.

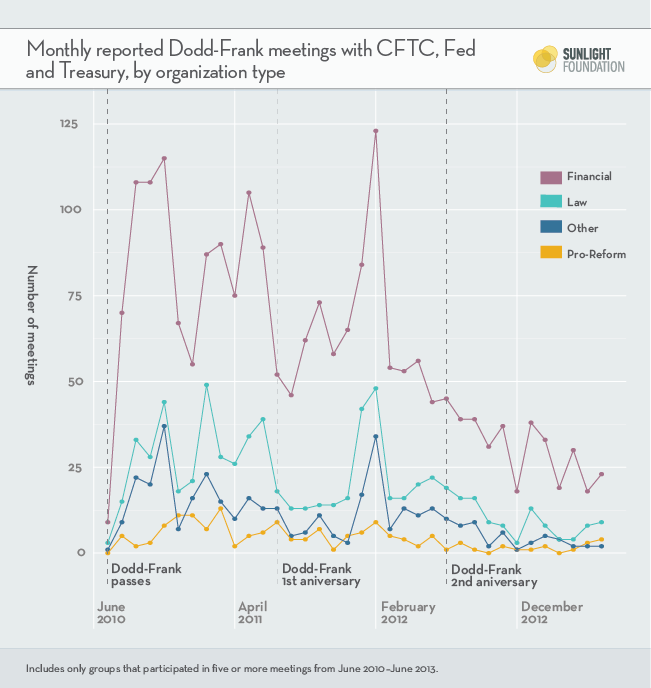

Figure 5 breaks out meetings by organization, by month. There is not a single month in which the three financial regulatory agencies did not meet most often with financial groups. The number of meetings does decline over time. The spike in February 2012 appears to be associated with substantial meeting activity around the Volcker Rule and Derivatives.

Figure 5.

Who meets together?

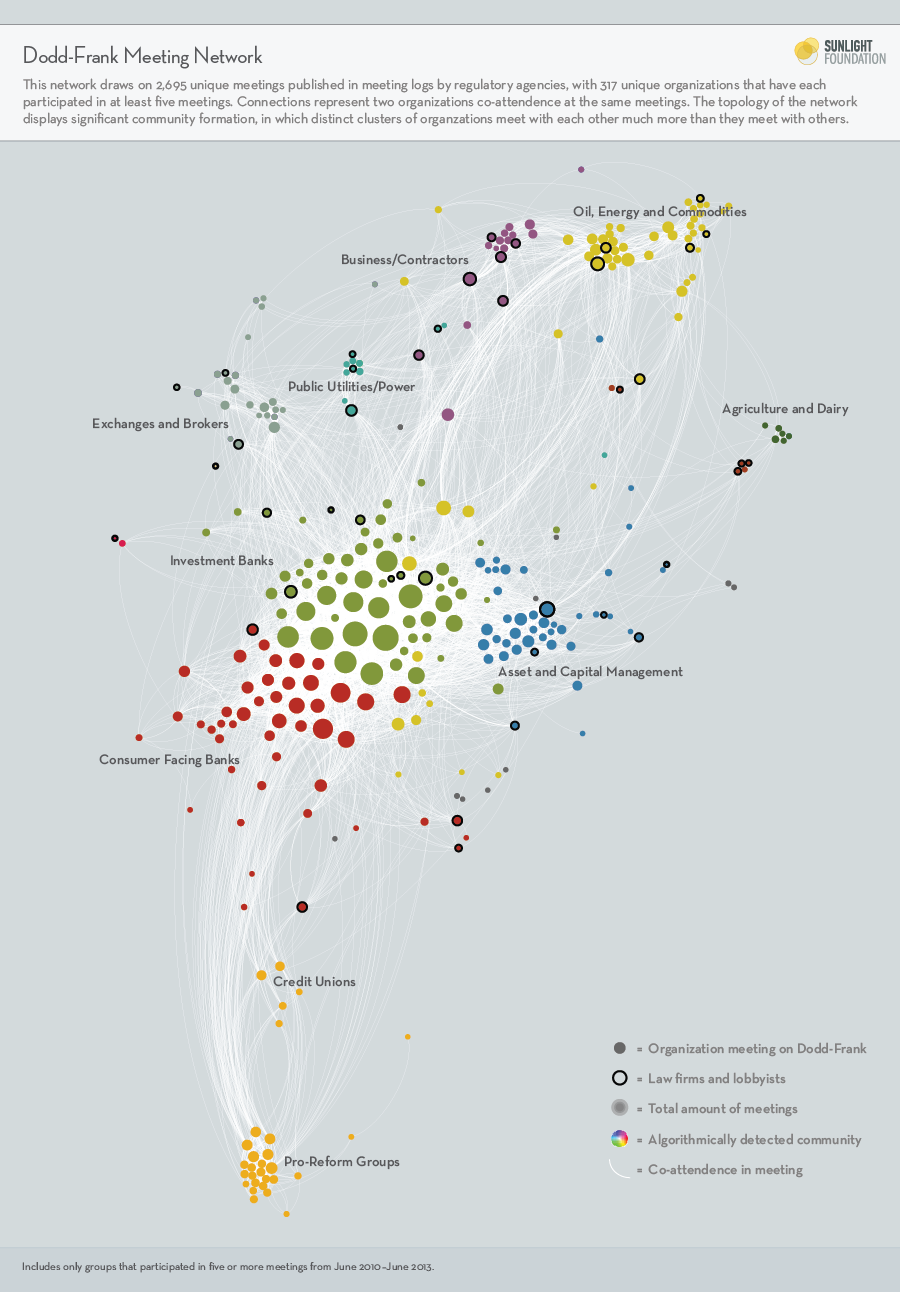

Finally, to get a sense of how the different interests meet together, we made a network visualization (Figure 6) of based on the co-attendence of 317 unique organizations at 2,685 unique meetings in our dataset. In this network, any organization that was in at least five meetings appears as a circle. Size is based on the total number of meetings an organization participated in. Organizations are connected to each other if they attended the same meeting. The more meetings they were in together, the stronger the connection between those two organizations. As a result, organizations that are the most connected appear in the center of the network, while those who are less connected appear in the periphery. Organizations that are close to each other attended similar sets of meetings with similar groups of other organizations. In this network, we go beyond our four category typology, instead relying on the network analysis itself to determine categories, using a standard community detection algorithm to categorize and color organizations. This allows us to observe differences between sub sections of the finance industry and the general business sector. Law and lobbying firms are given black outlines to see where they fit in.

Figure 6.

A few salient points emerge from the network.

First, as we might expect, investment banks are at the center of the network and have participated in the most meetings. Consumer facing banks as well as asset and capital management organizations, though slightly more peripheral, are tied closely to investment banks, indicating frequent meeting co-attendence between these communities.

More interestingly, the pro-reform groups are off in their own cluster. There is some overlap with credit unions, which in turn have some overlap with consumer-facing banks. In short, as the bank becomes more consumer-facing, it has more meetings in common with pro-reform groups.

There are also distinct clusters of other corporations. The big corporate interests that emerge are energy companies and agricultural companies, which are the most common end users of derivative products. Exchanges and brokers and public utilities, which have their own interests in derivatives, also form their own clusters, though there is some overlap. The network position of these clusters indicated that they are frequently in meetings with organizations within their own community, less frequently in meetings with the big finance players and essentially never in meetings with reform groups.

We can also see who the law and lobbying firms tend to represent by seeing what types of interests the network groups them with. The great majority of the law and lobbying firms are representing corporate interests and appear roughly split between the financial sector and other types of corporations.

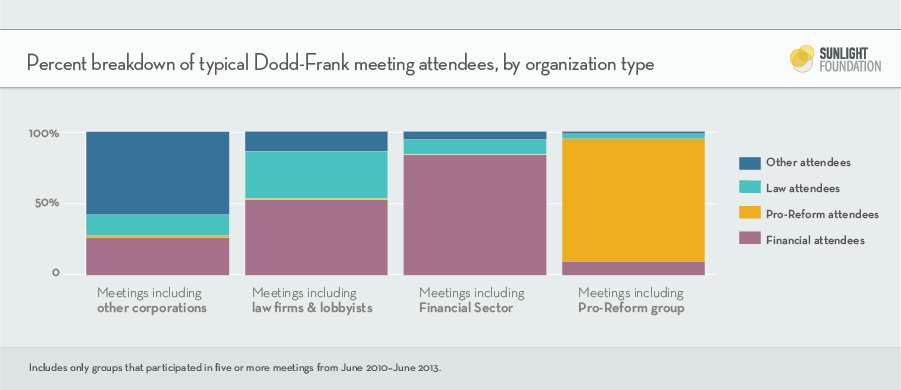

Figure 7 looks at the average makeup of meetings that include each of our four organization types. As shown in the network diagram, pro-reform and financial sector groups are relatively insular. An average of 85 percent of the participants in meetings including pro-reform groups are other pro-reform groups, while an average of 84 percent of the participants in meetings including financial sector groups are other financial groups. Lawyers and lobbyists, who are scattered throughout the network, meet more often with financial-sector groups (53 percent of meeting participants) than they do with themselves (33 percent of participants).

Taken together, both above figures show us that it is very rare indeed for regulatory agencies to hear from financial sector and pro-reform representatives at the same meetings. The two sides rarely get to confront each other and argue directly in the presence of regulators. Rather, they have separate audiences. And, again, one side gets 14 times more attention.

Figure 7.

Conclusions

The data plainly show that regulators are hearing from the representatives of affected banks over, and over and over again. With each meeting, bank representatives are getting yet another chance to make their case.

At least some experts believe the barrage of pleadings has had its intended effect.

“Much of Dodd-Frank is dying on the vine.” CFTC Commissioner Bart Chilton said recently. “Lobbying, litigation and lawmakers who have tried to defund and defang Dodd-Frank have all brought rule-writing to a crawl. Regulators themselves have become overly concerned about finalizing rules. Over-analysis paralysis, fears of litigation risks, and the lack of people-power have all contributed to the slowdown.”

As of July 1, barely a third (155) of the 398 total rulemaking requirements put in place had been completed, according to a Davis Polk report. Of the 279 rules with deadlines that have passed, 175 (62.7 percent) are still awaiting finalized rules.

Take one of the most hotly contested rules mandated by the Dodd-Frank legislation: the “Volcker Rule,” a proposal to limit risky trading by banks.

Wall Street hates this rule. And it has done everything it can to argue against it, raising endless questions. The best guess is that 16,500 of the public 17,000 comments on the Volcker Rule supported it as originally proposed, most of these organized through letter writing campaigns by reform groups. But as the Wall Street Journal’s Victoria McGrane noted: “These letters don’t make the sophisticated, foot-noted economic arguments of the more than 250 letters that aren’t considered form letters by the regulators.”

When it came to actually discussing how to write the Volcker Rule, more than 90 percent of regulators’ reported meetings involved sitting down with the corporate interests whose profits would be directly affected by the rule. The result: Originally slated to be finalized in July 2012, the rule is now not scheduled to be written until 2014. And the increasing consensus is that even if it is ever implemented, it will be so full of exceptions and loopholes as to be meaningless.

The definitive piece on the cumulative impact of relentless, often highly technical, objections on overburdened regulators is Washington Monthly editor Haley Sweetland Edwards’ excellent and exhaustive article on Dodd-Frank implementation, “He Who Makes the Rules.”

The best academic research on lobbying agency rulemaking comes from Amy McKay and Susan Webb Yackee, who found that when lobbying is “imbalanced” (as it often is), agency rulemaking tends to be responsive to the side that participates most. As they note in their article Interest Group Competition on Federal Agency Rules: “Lobbying requires considerable time and money to monitor agencies, research policies, and convince the bureaucrats that a group’s position is the right one.” Financial institutions have these kinds of resources. Pro-reform groups rarely do.

Bottom line

Regardless of how we cut the data, the same striking pattern holds: financial institutions, especially the big banks, are dogged and ubiquitous. Pro-reform groups are stretched thin. Lawyers and lobbyists are also active participants, primarily representing the banks. A number of other corporations show up frequently, most commonly in the energy and agro-business sectors, where derivatives and other market hedges are common practice.

To be sure, large financial institutions are also concentrating substantial efforts on lobbying Congress to roll back some of the legislative authority granted in Dodd-Frank as well as using the courts to legally invalidate portions of the legislation.

But the meetings log data provides perhaps the clearest quantitative measures of specific activities. Collectively, the data offer a powerful testament to the oldest and still perhaps most effective technique in the lobbyist’s playbook: sheer persistence.

As the Dodd-Frank law passes its third anniversary, lagging on deadlines, and increasingly defanged, the meetings log data offer a compelling reason why: the banks have overwhelmed the regulators.

Methodology: The data and their limits

This analysis is based on agency meeting logs data pulled from Sunlight’s Dodd-Frank meetings tracker. The raw, uncorrected data is available on ScraperWIki. We’ve done our best to clean it up, though it is possible that we missed certain meetings because of the many ways in which different organizations are listed in the records.

Unfortunately, our analysis here is limited to just three agencies. While five agencies agreed to post data online about meetings that involve outside groups regarding Dodd-Frank implementation, these reports vary in timeliness and format. Due to concerns about data quality and comprehensiveness, we excluded both the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). In the case of the SEC, the meetings are not organized in such a way that the Dodd-Frank meetings can be clearly delineated. In the case of the FDIC the meetings reporting appears very limited.

The other three agencies – the Treasury, Fed and CFTC – do post data online, but none of the three do so in a machine-readable, downloadable format. While we are reasonably confident that their reports represent a mostly accurate picture of meetings activity, they may also contain some shortcomings.

Although the agencies involved in implementing the Dodd-Frank bill voluntarily agreed to disclose meetings, each did so on its own timetable and according to its own standards.

In a separate post, Sunlight’s Nancy Watzman explores the limits of these data, noting for example, that when Elizabeth Warren was at Treasury, she was overzealous in documenting meetings, while Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner is suspiciously absent from meetings log data. In addition, Sunlight has found examples where agencies are late to post information and when officials neglect to report meetings (until absence is pointed out). If anything, the available data may undercount meetings with financial institutions.

Our categorization scheme breaks participants into four categories. We use “pro-reform” to describe organizations who are members of the Americans for Financial Reform coalition, which represents consumer and labor organizations. We also include the pro-reform group Better Markets.

Financial Sector includes financial corporations and associations. Law and lobbying firms and other corporate should be self-explanatory. We found a few local, federal and international government representatives appearing in meetings, but because they were so rare, we did not include them as a major category.

We also limited our analysis to only organizations that show up at least five times in the meetings logs, in order to make our coding and name standardization tasks feasible. This means that our analysis misses 22 percent of meetings. While it would be great to have all the meetings, the additional time cost of cleaning and coding the long tail of organizations that show up only a few times did not seem worth the analytical benefit. Our data go through June 30, 2013.

Again, we re-emphasize that our analysis is only as good as the raw data we get from the regulatory agencies. So we take this opportunity to reiterate a frequent Sunlight plea: for more disclosure and for document disclosure in machine-readable formats that are easy to use and analyze.