In its first year, the Trump administration has reduced public information online

From the redesign of the White House website to the removal of hundreds of Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) webpages about climate change, the Trump administration, as part of transforming the federal government in its first year, has already left a distinct mark on federal websites.

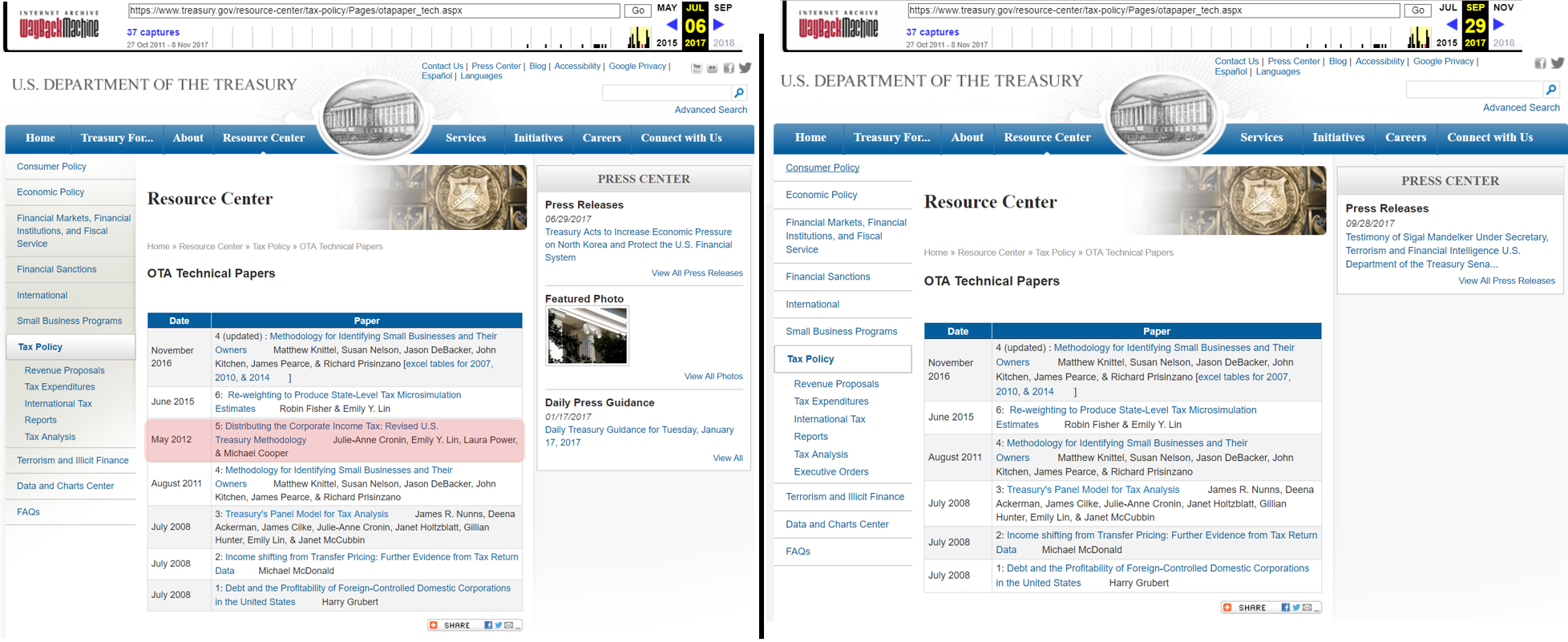

In some cases, we’ve observed politically motivated and otherwise unexplained removals of documents and entire websites. The Department of the Treasury removed a non-political, research report about corporate income tax from the Office of Tax Analysis website. According to numerous sources, the report was likely removed because it was at odds with Secretary Steven Mnuchin’s tax policies.

Despite widespread concern in the beginning of 2017, we do not have evidence that data has been removed from federal websites almost a year into the Trump presidency. The one exception we know of is the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s animal welfare datasets, which was taken down and then partially returned following public outcry and several lawsuits.

What we have seen are substantial removals and overhauls of webpages, documents, and entire websites, as well as significant shifts in language and messaging across the federal Web domain. We know this because we’ve been monitoring tens of thousands of environmental federal webpages at the Environmental Data & Governance Initiative (EDGI) and keeping tabs on relevant reporting and investigations by members of the press and civil society in our roles as Sunlight Fellows.

Removal of a corporate income tax report from the Department Of The Treasury’s Office Of Tax Analysis website

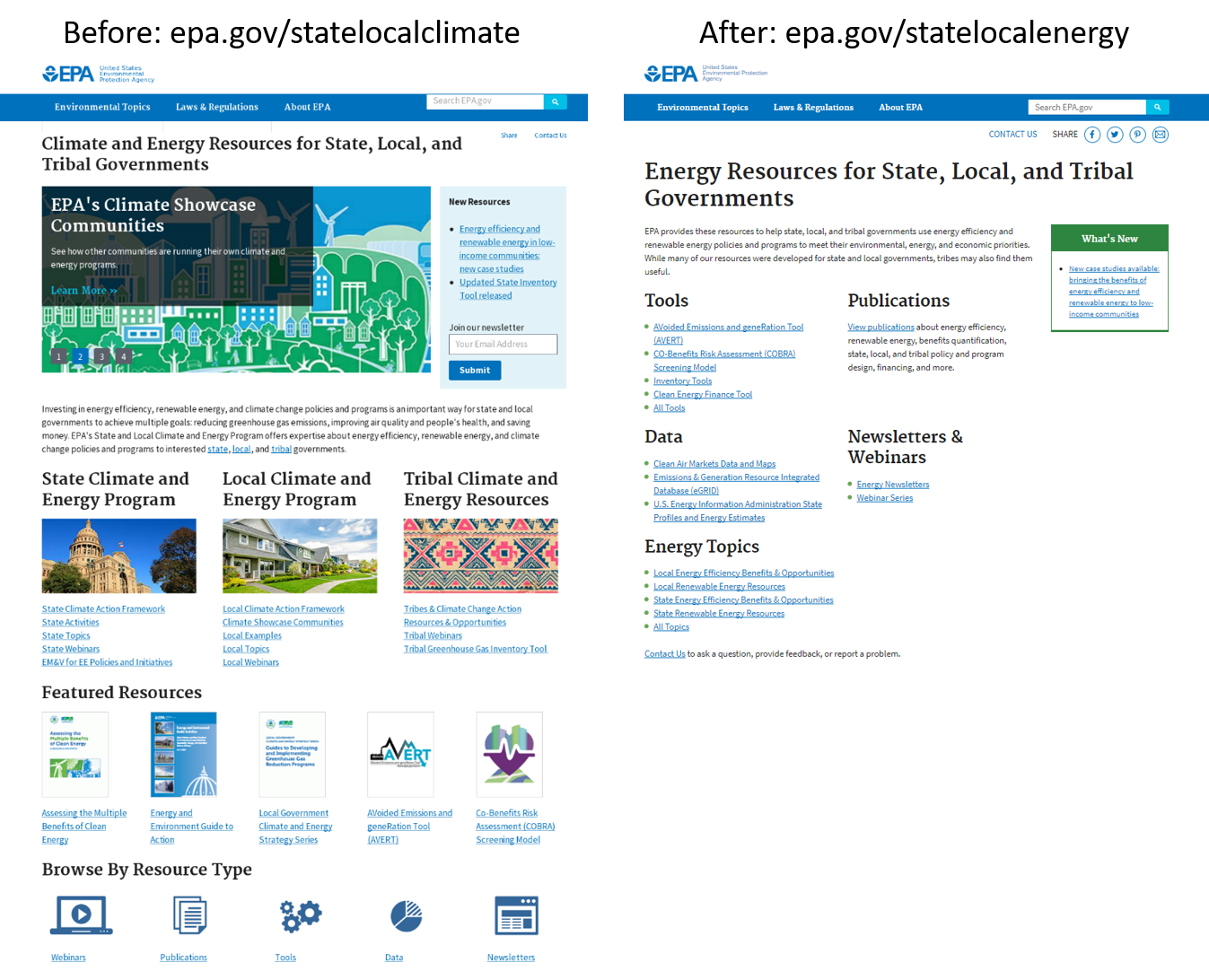

The most significant reduction in access to federal resources occurred at the EPA when its climate change website was removed on April 28, 2017. This is only part of the censorship of climate change Web content that has gone on at the EPA and across federal websites. The site has been down, without a legitimate explanation for more than eight months. A portion has been returned, but with mentions of climate and almost all climate Web resources removed.

The EPA’s Climate and Energy Resources for State, Local, and Tribal Governments website was removed and replaced by another site omitting climate change information.

Career staff have also changed messaging on websites to align with the priorities of the new administration. At the Department of Energy, the Clean Energy Investment Center was renamed the Energy Investor Center. According to The Washington Post, staff not authorized to speak on the record claimed “It’s our own career staff. They’re in their keep-their-head-down, ‘maybe they won’t cut our budget’ mode.”

It’s difficult to quantify the full extent of website changes across the .gov Web domain, although those efforts are underway. We’ve been paying closest attention to environmental, energy, and climate websites, and we can say with certainty that thousands of those pages have been altered, overhauled, or removed. That number, however, is misleading on its own.

Some alterations to websites are expected and necessary for regular updates to information, while others, which we’ve tried to highlight as much as possible, are unjustified reductions in access to public resources. To that end, we’ll be making use of our classification of Web content alterations and changes in access to Web resources to compile much of what we have seen in a public tracker in the coming weeks. This will allow us to capture the scope and significance of the changes we’ve seen in a contextualized and meaningful way.

Agencies need to get better at communicating

In almost all cases we’ve seen thus far, agencies have not proactively disclosed how, when or why they alter their websites. In fact, agencies have often offered explanations only after the news media and watchdog groups, such as EDGI or the Project on Government Oversight, have brought attention to particular website changes.

Quiet manipulation of Web content can sometimes backfire and draw negative media and public attention for the wrong reasons. In one case, alterations to a search engine on the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) website generated unnecessary public confusion. An update to the search function reduced the number of results that the engine was producing. Focusing only on changes to results for the term “climate change”, the public and the news media accused the government of politically targeted removals of climate Web content, when this was not what had actually occurred.

USGS could have mitigated this confusion by proactively announcing changes to their search function, and we should hold them accountable for not doing so. But with limited news media bandwidth and a variety of issues related to government accountability at the fore, we should also make sure to get the story right.

This is especially important to consider as real issues of censorship across agencies are being brought to light, beyond the website censorship described above. At the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, budget policy analysts were told not to use a list of forbidden words or phrases, including “evidence-based”, “transgender”, and “diversity”. Political appointees at both the EPA and the Department of the Interior are getting more involved in deciding what to disclose in response to Freedom of Information Act requests.

Public website governance

Underlying the changing federal Web landscape are complicated Web governance issues that still need to be addressed. Sunlight supported the proposed Preserving Data in Government Act, which, if passed, would require agencies to provide sufficient public notice in most circumstances before any data sets are removed from the Internet.

Along with the American Library Association and OpenTheGovernment, Sunlight wrote a letter to the National Archives and Records Administration outlining what it should focus on as it updates its 2005 Guidance on Managing Web Records, including helping ensure that agencies provide public notice prior to changes and prioritize Web resource accessibility by creating public Web archives whenever possible.

We hope that our classification of Web content alterations and changes in access to Web resources can continue to serve as a framework to clearly describe the different types of changes to federal websites, which should often be addressed in very different ways.

Why does continuing this work matter?

According to the U.S. government’s own assessment, there were about 2.5 billion visits to .gov websites in the past 90 days. That number is around 400 million for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), over 33 million for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and over 86 million for the Department of the Treasury.

As long as the Internet and the federal government continue to exist, people will continue using the vast .gov Web domain as a valuable public resource. These websites are not just useful because they facilitate and explain various government functions; they also serve as the foundation for our democracy, providing a wealth of scientific, policy, educational, and historical information that is necessary to enable an informed and engaged public.

Given the limited scope of the website monitoring effort so far, there is certainly much that we have missed. In the new year, as new budgets are drafted, more regulations are rolled back, programs are sunset, a new national security strategy is acted on, and the Trump administration continues to evolve, efforts to hold the federal government accountable for how it presents Web information will need to scale accordingly.