Reporter’s Notebook: Understanding the automatic cuts if the supercommittee can’t deliver

With the supercommittee's deadline only five days away, the special deficit-cutting panel's chances of reaching a deal appear to be in doubt. And if no agreement is reached, more than one trillion dollars in cuts would be set in motion starting in 2013. That is, if the Congress and president allow the automatic trigger to take effect.

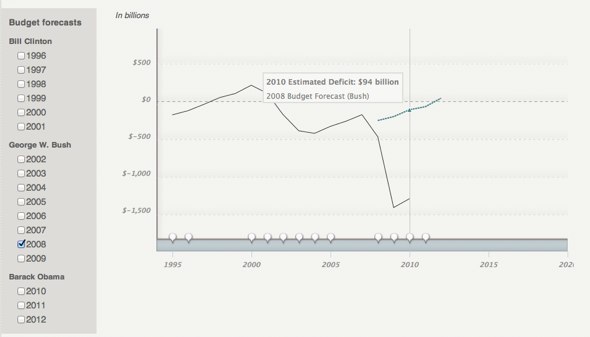

All of this is predicated on budget forecasting, a notoriously inaccurate art. As the CBO pointed out in a September report, an analysis based on projected baseline budgets and economic projections are “subject to a considerable degree of uncertainty.” Indeed, we recently published a new interactive feature demonstrating how past budget plans have rarely matched up with reality (click the image to launch the graphic):

The possibility of triggered cuts was part of the deal to lift the nation’s debt limit in early August. To create an incentive for the panel (known as the supercommittee and also created by the debt limit deal) to slash the nation’s deficit, the law called for $1.2 trillion in automatic cuts from 2013 to 2021 if the 12-member panel did not come up with a bipartisan deal of its own.

So, what would the cuts target? Several organizations have tackled this question:

- The Congressional Budget Office analyzed the economic impact of the cuts in September;

- The watchdog OMB Watch examined how the supercommittee sequester process works;

- And Richard Kogan, a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) looked at how the across-the-board cuts would unfold in 2013.

The numbers

The panel must cut $1.2 trillion from the deficit to avoid the triggered across-the-board cuts to discretionary and mandatory spending that would start in 2013. If the supercommittee eliminates less than $1.2 trillion, the balance would be cut via the trigger between 2013 to 2021.

Both the supercommitte cuts and the triggered cuts would be in addition to $900 billion in spending caps imposed by the August debt limit deal, officially called the Budget Control Act.

But, as in all things Congress, there are a lot of asterisks.

- The Budget Control Act actually sets a $1.5 trillion goal for the supercommittee, but the trigger applies only if the $1.2 trillion figure isn't reached.

- Potential debt service costs savings (that is, the interest on government debt) of about $200 billion are already included in the $1.2 trillion figure.

- Congress can still spend through emergency measures. All such spending, including discretionary spending for wars, increase the budget caps, OMB Watch explained. Congress can also pass a limited amount of disaster relief spending.

- The CBO says some of the savings would occur after 2021, due to the lag between appropriating funds and actual spending.

- No Congress can bind the actions of a future Congress, so if a future Congress wants to change course, it needs only to pass new legislation.

Savings breakdown

As shown below, 71 percent of the cuts in the trigger are to discretionary spending, according to the CBO. Thirteen percent comes from mandatory spending and 16 percent comes from lower debt service costs, the CBO estimated.

Discretionary spending is any funding determined by Congress, such as the annual appropriations bill for the Department of Labor and other agencies. Mandatory spending, which amounts to about two thirds of the budget and is mostly made up of entitlements, is determined by eligibility rules.

Here’s how CBO breaks down the savings from the trigger:

- Defense discretionary: $454 billion

- Nondefense discretionary: $294 billion

- Nonexempt mandatory defense: $100 million

- Nonexempt mandatory nondefense: (mostly from lower Medicare payments to providers): $170 billion

- Debt-service: $169 billion

- Total: $1.1 trillion

If the cuts are triggered, the discretionary spending cuts passed in the August bill would carry through to 2012.

The $1.2 trillion in cuts would come on top of this and would also be split evenly between defense and non-defense spending; there would be about $55 billion in reductions to each side each year. There would also be annual slashes to mandatory programs, the majority of which will come from Medicare.

What's exempt?

About 70 percent of mandatory spending is exempt from the reductions, according to the CBO. That includes Social Security, Medicaid, food stamps, other entitlement programs, the earned income tax credit, and many others programs. Cornell University Law School provides a full list here.

Will the cuts actually take effect?

If the supercommittee fails to reach a deal, or agrees to cut less than $1.2 trillion, "it would set up a yearlong effort to prevent the across-the-board cuts from ever going into effect or to get credit for trying," Stan Collender, a former Congressional budget staffer and current partner at the public relations firm Qorvis Communications, wrote in a column for the newspaper Roll Call.

Collender said that three things could happen. First, the president and Congress could decide to simply undo the law. Second, they could adopt something to replace it. Finally, they could decide that it's not wise for the cuts to begin in January 2013 and delay them.