Special interests honor Congress, executive branch with nearly $19 million in 2011

Spurred by reports that Smartphone software made by Google and Apple could violate users' privacy, a Senate Judiciary subcommittee called executives from the companies to testify in May 2011. For the most part, the senators were uncharacteristically deferential to the hi-tech titans appearing before their panel. In his brief opening statement, ranking member Tom Coburn, R-Okla., said, “We need a whole lot more information and knowledge in terms of those of us on the legislative side before we come to conclusions about what needs to be done.”

One day later, Coburn was recognized at a Consumer Electronics Association event for his “unwavering support of technology and innovation.” Among the sponsors of the event: Google, which kicked in $25,000.

Google’s charitable gift is a drop in the bucket of the nearly $19 million that lobbyists for corporations, trade associations and other special interests paid to rub elbows with and pay tribute to members of Congress and executive branch officials in 2011, down from $23.2 million the year before. The total comes from an analysis of bi-annual contribution disclosures filed by lobbyists and the companies and firms that employ them. The disclosures list, among other things, “honorary” and “meeting” fees, such as sponsoring events where a lawmaker receives an award or paying the costs of a meeting with a legislator. The reports were required by a 2007 ethics law meant to increase transparency on the influence of lobbyists in Washington.

While Congress’ public approval ratings may be dismal, special interests spent over $15 million honoring its members and their various caucuses. They spent some $3.5 million honoring executive branch officials. The remainder was spent honoring legislative branch staffers and candidates for federal office.

The money generally goes to organizations doing charitable work. But for the lobbyists that donate, it gives them an opportunity to promote their clients’ interests and to get face time with policymakers. In many cases, companies and associations that lobby honor lawmakers that sit on congressional committees regulating their clients’ businesses. And, unlike political contributions made to candidates’ campaigns, which are limited to $2,500 for individuals and $5,000 for political action committees per election, gifts to lawmakers’ causes are unlimited.

The kinds of gifts considered “honorary” fall into many categories, including giving to a nonprofit where a lawmaker is on the board of directors, sponsoring an event where he or she receives an award, or giving to a nonprofit in recognition of an official. “Meetings fees” usually mean paying the costs of a retreat, conference or other event put on by a lawmaker or foundation associated with lawmakers, such as the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Foundation. Honorary expenses make up the vast majority of the giving.

One change from 2010 to 2011 in honorary giving was the increased generosity of Google and General Motors, which have both ramped up their presence in Washington in recent years for different reasons.

As Google doubled its lobbying operations from 2010 to 2011, it quadrupled its charitable giving at events honoring lawmakers, from about $65,000 to more than $240,000, becoming the 19th biggest spender honoring officials. The search giant is fighting multiple high stakes battles in Washington—an antitrust investigation from the Federal Trade Commission, a fight over online piracy legislation, which it won despite being outspent by Hollywood interests, and concerns over the company’s privacy policies.

General Motors stopped honoring lawmakers, reports show, during a self-imposed ban on political contributions to candidates’ campaigns (though it never stopped lobbying) when the government was financing its bankruptcy in the spring of 2009 amidst the recession. As GM returned to making those political contributions in 2010, it also began honoring lawmakers again.

By 2011, it doubled its charitable giving from 2010–to more than $368,000, landing it at 13th on the list of givers.

The biggest contributors

Twenty-five entities—mostly corporations but some trade associations, advocacy groups and universities—account for about half of all the honorary contributions.

Many of the biggest donors at the top of the list in prior years stayed there, including Wal-Mart, 2011’s top donor, Chevron, 2009 and 2010’s top donor, and military contractor Triwest Healthcare, which ranked third in 2011. The oil and gas sector, auto industry, tech and telecom world, transportation, defense and the food and beverage industries dominated the list. Of the top twenty, only Triwest Healthcare and a pair of universities did not have multi-million dollar lobbying budgets.

General Motors’ competitor, Ford, has dropped off in recent years—it gave a whopping $800,000 in honor of lawmakers in 2009, mostly to civil rights causes, making it the sixth biggest contributor in 2009 and 2010. But it gave about a quarter of that total in both 2010 and 2011, when it fell to 20th on the list. In contrast, Toyota’s giving has not trailed off–it has stayed in the top ten in 2011.

Google’s fierce competitor, Microsoft, disclosed no honorary gifts in 2011, after just a handful of them in 2010. But two other competitors in the tech world—AT&T and Comcast, both outspent Google in such giving. In 2011, AT&T, ranked 11th, sought support for its ultimately unsuccessful attempt to acquire rival cellular provider T-Mobile. That year, Comcast, after successfully acquiring NBC-Universal from General Electric, faced Justice Department scrutiny of the deal. The cable company ranked eighth on the list.

The honored officials

Compared to the last Congress, when Democrats held both chambers, the tables have turned–but only to a point. Then, Democrats drew the most honorary contributions from lobbyists, with the late Sen. Ted Kennedy leading the way. In the new Congress, the GOP has taken over the House of Representatives, and some Republicans are getting far more attention from lobbyists. But Democrats were still honored more: $5.1 million worth compared to $4.2 million for their opposition.

Overall, the two most honored officials, in terms of total dollars spent on events involving them, were Republicans: Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, and Senator Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn. Much of the money honoring Boehner was for an annual event raising money for one of his pet causes: school choice. The annual dinner raises money for private inner-city elementary schools in Washington. Corporations pay up to $50,000 to sponsor the event.

Overall, the two most honored officials, in terms of total dollars spent on events involving them, were Republicans: Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, and Senator Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn. Much of the money honoring Boehner was for an annual event raising money for one of his pet causes: school choice. The annual dinner raises money for private inner-city elementary schools in Washington. Corporations pay up to $50,000 to sponsor the event.

The big spending for Alexander came on the weekend he was invited to the Vanderbilt University Hall of Fame. Among other costs, the university paid nearly $40,000 to archive the former Tennessee governor’s papers and video records. The school also put on a reception to open an exhibit showcasing them. Overall, Vanderbilt disclosed more than $500,000 in payments to honor Alexander.

Of the Democrats, Assistant Minority Leader James Clyburn, D-S.C., was again among the most honored as corporations and lobbyists lined up to donate to his annual South Carolina golf tournament benefiting an eponymous charity that provides college scholarships to needy students.

Another top Democratic awardee was Senate Whip Dick Durbin, D-Ill. Pharmaceutical companies lined up to sponsor a dinner honoring him for bolstering the health care research funding in the 2010 health care system reform law. Pharmaceutical companies lobbied heavily for the health reform law, after cutting a deal with the Obama administration beneficial to their bottom lines.

But year after year, the biggest overall recipient of corporate and lobbyist money are the independent foundations that support the lawmakers in the Congressional Black Caucus and Congressional Hispanic Caucus. Caucus members sit on the foundations’ boards of directors.

Of the over $15 million in contributions honoring lawmakers, $5.7 million went to honoring caucuses such as this and $9.6 million went to honoring individual lawmakers, according to the analysis of 2011 reports.

The ‘benign’ influencer

Google paints itself, even in Washington, as a benign influence, touting its ‘Do No Evil’ motto. It hosts hip events at its D.C. headquarters with authors—such as its D.C. Talks series featuring an event about beer making. At a hearing last year about the company’s potential antitrust violations, the firm’s CEO said it is a different kind of company because it's not a typical "rational business trying to maximize its profit."

But according to Carmen Balber, the Washington director for Consumer Watchdog, a California-based nonprofit, the company has become part of the “traditional inside-the-beltway-D.C.-lobbying-game.” Its levitating lobbying budget “belies the benign image they’re trying to display,” she said.

The Palo Alto company’s lobbying expenditures—nearly $10 million in just the first half of this year—have now surpassed all other tech and telecom companies other than AT&T. Its employees’ and political action committee’s campaign contributions crossed the $1 million mark in the 2006 election cycle and never dropped below it.

The search giant argues that the lobbying increase is a natural response to a growing number of technology issues being debated in Washington. It also faces competitors like Microsoft with a longstanding footprint in the nation’s capital.

But it’s also made certain policy issues a priority, particularly keeping lawmakers away from introducing “do not track” online legislation, according to Balber.

“There is not a key piece of legislation that has gotten a lot of traction yet because they’re really pushing the issue,” Balber said.

This lobbying push has been matched by an increase in charitable giving. Its largest honorary gift was a $70,000 sponsorship of the annual summit by the Future of Music Coalition—a musicians’ advocacy group–where it honored former Federal Communications Commissioner Michael Copps. At the time, Google had in interest in numerous issues being considered by FCC—such its National Broadband Plan, universal service fund reform and spectrum auctions.

The company spent $80,000 giving to charities that honored nine members of Congress in 2011, including Coburn, whose press secretary did not return a phone call asking for comment.

A Google spokeswoman, Samantha Smith, declined multiple requests to comment for this article.

General Motors

After growing to be the 12th biggest spender in 2007 on lobbying expenditures—at over $14 million—GM bottomed out at $8.4 million in 2009, the year the government rescued the company. But it has steadily increased that budget to almost $11 million in 2011, all while giving more to honor lawmakers, too.

“While our giving is comparatively less than other large companies and some of our competitors, we are pleased that our improved business performance has allowed us to increase our recent giving,” GM spokeswoman Heather Rosenker said.

GM was a gold level sponsor at a popular annual dinner for corporations and lobbyists seeking to influence policymakers that benefits four Catholic schools in Washington. Named after Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, Sen. Joe Lieberman, D-Conn., and former D.C. mayor Anthony Williams, the event offered GM, for its $50,000 gift, eight prime tickets to the dinner, tickets to the private pre-event reception, and two invitations to a sponsor appreciation breakfast.

Another $75,000 went to three charities in honor of home state lawmakers. That included a $25,000 donation to the Foundation to Eradicate Duchenne, a form of muscular dystrophy, which honored powerful House Energy and Commerce chairman Fred Upton, R-Mich., at its annual dinner in late 2011. Upton was one of many Michigan lawmakers who supported the auto industry bailout. But he is also the sponsor of a bill pushed by GM that would prevent the Obama administration from classifying greenhouse gases as pollutants. That’s just one of the many bills that GM is lobbying Upton’s committee on.

Rosenker said GM gives to organizations that have worthwhile goals. In this case, the company donated because Duchenne gets little attention but affects many people, including GM employees, she said.

A spokeswoman for Upton did not respond to multiple messages.

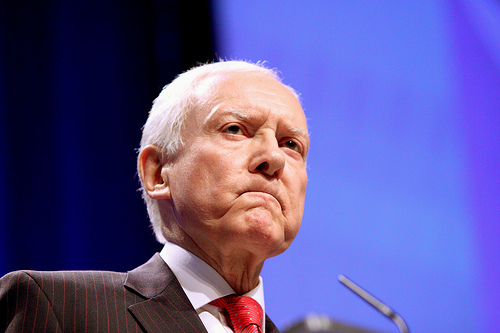

Cosmetics industry honoring Orrin Hatch

The reports also shed light on who is giving to lawmakers’ associated charities, such as the one that Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, helped start: The Utah Families Foundation, which benefits needy women and children in the state. He is a main draw at an annual golf tournament sponsored by many corporations, including, historically, many pharmaceutical companies. He attended in 2011 as he usually does.

An unusually high contribution for the event came in from the Personal Care Products Council, a trade group for the cosmetics industry. The amount of the group’s donation has been increasing each year—from about $36,000 in 2008. This was an in-kind donation of products such as perfume, lotion, toothpaste and face products; the goodies went to the other sponsors of the event, and the council got its name listed on the tournament program alongside other donors, according to the UFF’s director Sheri Sorenson.

Amidst concerns from watchdogs and the public about the health impacts of ingredients in cosmetics products, the council has been trying to advance a bill it wrote, sponsored by Rep. Leonard Lance, R-N.J., that critics claim minimizes regulation of the ingredients used in cosmetics products. In recent years, watchdog groups and news reports have raised concerns about mercury in skin whitening cream and formaldehyde in hair-straightening products.

The industry currently polices itself by funding a self-regulatory body called the Cosmetics Ingredients Review (CIR), housed in the same office building as the PCPC. The Food and Drug Administration has no authority to force recalls of certain ingredients–that would not change under the industry-backed bill.

“They’re trying to get cosmetics reform passed in name only,” said Jason Rano, a lobbyist for the Environmental Working Group, part of a coalition called the Campaign for Safe Cosmetics (CSC). The EWG and the Breast Cancer Fund, concerned about the long-term effects of toxic chemicals, have been lobbying for a bill that gives the FDA more authority.

Lisa Archer, the director of the Breast Cancer Fund, called the industry bill a “codification of the status quo.”

The PCPC is likely looking for a Senate sponsor, Archer said, and Hatch would be a good candidate because the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee veteran has been a friend to other industries looking to keep the FDA at bay. After the FDA drafted new regulations for the dietary supplement industry, which were opposed by the industry, Hatch and Sen. Tom Harkin, D-Iowa, wrote a letter to the FDA asking it to withdraw the rules, then met with agency officials in June. The agency said it would revise its guidelines to address some of points raised by the lawmakers, according to a FDA News report. And earlier this year, Hatch and two colleagues also sponsored a bill to speed FDA approval of certain “breakthrough” drugs; his measure passed the Senate in May as part of a larger bill and was signed into law in early July.

Hatch’s spokeswoman, Heather Barney, called the idea that the PCPC is trying to influence Hatch unfair. “They didn’t just realize they had an issue and start donating now,” she wrote.

She added that the Utah Families Foundation’s executive director solicits all of the donations, and her boss makes no decisions for the group. Hatch did help launch it about two decades ago–he envisioned the charity and consulted Utah business leader who formed a board of directors, according to Barney.

The PCPC’s head of government affairs, John Hurson, said that the organization has a long history of giving away cosmetics products at charitable events.

Hurson wrote that the PCPC is open to compromise on the bill it backs, saying, “The industry is ready to respond with reform proposals that go beyond the current language of the Lance bill, H.R.4395, on mandatory recall and fragrance ingredient disclosure.”

The watchdog groups also criticized the Lance bill for not increasing the FDA’s budget. But Hurson wrote that the PCPC has spent five years trying to increase the FDA’s Office of Cosmetics and Colors’ budget. He wrote that the budget has tripled in recent years to $11.7 million.

According to the analysis, the amount of money from lobbying entities going towards lawmakers’ causes and awards declines more and more every year. The nearly $19 million in honorary and meetings expenses is an 18 percent decrease from 2010, after the expenses fell by just 15 percent from 2009 to 2010.

There was an even more dramatic decrease from 2008 to 2009 but campaign finance lawyers attribute that to updated guidance issued by the Senate Office of Public Records and House Clerk in early 2009, which narrowed the definition of an honorary expense.

Overall, the giving has declined because it became transparent, according to Brett Kappel, a campaign finance lawyer at Arent Fox who advises companies on lobbying law compliance.

“No one wants to gives the impression that they’re tools of special interest,” he said, referring to members of Congress. Companies do not want to give when it’s public and members do not want to attract scrutiny, he said.

The law was intended to stop donations to potentially illegitimate lawmaker-controlled charities—not actual good causes. And Kappel said that goal has been largely successful.

Many lawmakers with personal charities—but not all—have either stopped soliciting donations for their nonprofits or retired from Congress since the law began, he added.

But not all of the honoring has ceased. Industry groups are still holding their annual galas that, for instance, honor lawmakers as legislators of the year, he said.

The money directed at some members reflected the decline. Clyburn’s charity golf tournament, despite the dozens of sponsors and around three dozen lobbyists who signed up for the event, raised less than the year before, according to the reports and Clyburn spokeswoman Hope Derrick. The lobbying disclosures show the foundation raised $222,000 from entities that lobby in 2011, barely more than half the 2010 total. Overall, charitable giving to the Clyburn Research & Scholarship Foundation for the tournament was about $400,000, a decrease of about $100,000 from 2010, according to Hope.

Lobbying companies and associations also disclosed far fewer donations to four charities associated with Sen. Jay Rockefeller, D-W.V., in 2011. The charities received $85,000, about a quarter of what they got the year before. The money went to the Blanchette Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute (where Rockefeller is the founder and honorary chairman), the Alliance for Health Reform (founder, honorary chairman), Discover the Real West Virginia Foundation (founder, honorary chairman) and the Washington Bach Consort (honorary board member).

On the other hand, donations to the Boehner-Williams-Lieberman dinner appears to have jumped up after Boehner became the Speaker of the House in 2011. The reported gifts increased by 50 percent to about $310,000, and that’s not even including the hundreds of thousands of dollars from corporations that lobby that went unreported because of one of the many loopholes in the law.

What is most striking about these disclosure requirements is how often they are not required. A congressman could ask a company lobbyist to donate to a charity of his choosing or buy a $40,000 table at a Washington gala where he receives an award all without disclosing it.

Consider the big dinner hosted by Boehner. Kaplan, the education company that owns the Washington Post, donated $50,000 but did not report it. That’s because the rules say if a congressman merely lends his name to an event but does not receive an award, it does not have to be reported, Kaplan spokesman Mark Harrad pointed out. Spokespeople for Goldman Sachs, the CME Group, Comcast, and Hilton Worldwide also said their $50,000 donations did not require disclosure.

It’s unclear if the gift was made in part to get in Boehner’s good graces. “You can’t know what’s in people’s minds,” Kappel said. But “It’s well known that he supports the charity” and the donation gives company executives access to him, Kappel added.

There are many other loopholes. A partial explanation for the decline in 2011 is the near disappearance of JPMorgan Chase, one of the nation’s biggest banks, from the totals. After being the third biggest contributing company in 2009 and 2010, giving more than $1.7 million, JPMorgan reported only one honorary gift in 2011, worth $40,000. A spokeswoman for the company, Jennifer Kim, said more donations would likely be reported for 2011 in amended filings. She blamed the delay in disclosure on the organizations the banks supports, which they rely on to tell the bank if a federal official is on its board of directors.

Still, because the donations disclosed by JPMorgan come from the bank’s charitable arm—a separate organization—they do not technically have to be disclosed. The 2009 and 2010 disclosures were made out of an abundance of caution, a spokesman said last year.

That’s just one area of murkiness. Only a handful of companies disclosed giving to the Utah Families Foundation in honor of Hatch, despite the fact that many more corporations that lobby likely donated. Technically, the companies do not have to disclose the gift unless the foundation is controlled, established, financed or maintained by an official, according to the Senate’s guidance. Though Hatch helped start the organization, he did not formally establish it.

Lobbyists can also purchase a table at a charity event where a member of Congress is honored as “lawmaker of the year” but not disclose the payment if it does not meet House and Senate’s narrow definition for what it means to be a sponsor.

If companies were to omit disclosing a gift on purpose, it’s unlikely they will face consequences. There has never been a penalty issued for failing to report an honorary gift, according to the U.S. attorney’s office for the District of Columbia, which is responsible for lobbying disclosure enforcement. The attorney’s office has never even received a complaint of such a thing. Last year, the Sunlight Foundation documented some omitted donations that likely should have been reported in 2009 and 2010.

Sunlight’s analysis covered about 1,550 payments. Where multiple officials were listed for the same payment, the amount was divided equally among each honoree. When non-legislative or executive branch officials were listed as honorees, they were deleted. Dozens of payments were deleted because they were obviously not honorary or meetings expenses—and should have been categorized as something else (such as campaign contributions) or not reported at all.

(Graphics by Jacob Fenton and Kevin Koehler)