Do members of Congress headline fundraisers in exchange for floor votes?

We at the Sunlight Foundation spend a lot of time looking over the political fundraising invitations that keep pouring into our Political Party Time website. So we were very excited to read a paper by Yale Political Science Professor Eleanor Neff Powell, who used our Party Time data to investigate an often underappreciated aspect of the political fundraising circle: headlining for others.

By carefully analyzing the corpus of fundraising invitations that we’ve compiled over the years, Powell was able to uncover evidence of an economy of favors in the Washington fundraising circuit. Members of Congress who headline events for other members get something in return – votes for their legislation. Or, as Powell puts it:

Controlling for the ideological similarity of their past voting records, a Democratic Congressman is 5.5% more likely to vote for a bill for each fundraising event the bill’s sponsor has headlined for them in the past (Republican Congressmen are 2.5% more likely). These results show a strong relationship between fundraising assistance and subsequent legislative voting behavior and suggest potentially serious consequences for representation

The findings are explained in more detail in Powell’s recent paper, “Dollars to Votes: The Influence of Fundraising in Congress.” But the basic takeaway is pretty straightforward. Headlining events for your colleagues is a darn good way to build up goodwill. And that goodwill systematically translates into more support for votes on the floor.

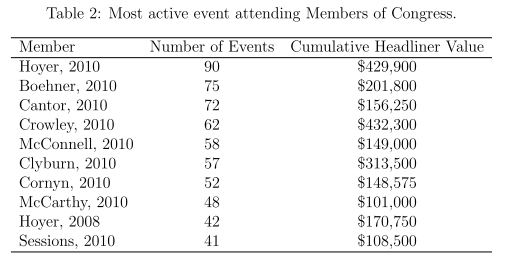

Powell compiles the list of the members of Congress who appear most often at others’ fundraisers. It will probably not come as a surprise that pretty much all of them are in party leadership.

Does it matter? Powell offers some of the consequences in her conclusion:

Members who frequently face expensive contested races for re-election are both consistently indebted to their colleagues, but also unable to accrue their own debts of gratitude. Thus these vulnerable members are both more likely to vote for contributing colleague’s legislative priorities, but also less likely to be able to recruit votes in a similar fashion for their own legislative priorities. Further, members who prove able and willing to draw in large-scale contributions and fundraising are substantially advantaged in achieving their personal legislative objectives.

In other words, those who are constantly in need of favors may need to compromise some of their positions – both because they have to vote for other members’ priorities and because they can’t build the same support for their own priorities. By contrast, those in safer seats have more luxury to build legislative coalitions through generous headlining.

Usually, we are troubled by fundraisers both because of the access that they provide to those who can afford to price of admission (usually on the order of one or two thousand dollars) and the way they take up members’ time. But Powell’s paper gives us another reason to be concerned about the fundraising circuit – the way in which it enables certain members to in effect trade headline appearances for votes.