Day after McCutcheon, FEC commissioners clash over dark money

The day after the Supreme Court threw aggregate contribution limits out of the window, commissioners from the nation’s campaign finance watchdog agency clashed over an enforcement matter from the 2010 elections. The issue at hand? The Federal Election Commission’s failure to investigate the political status of “dark money” republican nonprofit, Crossroads GPS.

Hours before the meeting, Vice Chair Ann Ravel — a Democrat who took an aggressive stance against dark money political contributions as head of California’s campaign finance enforcement agency — published an op-ed in the New York Times on Wednesday bluntly titled “How Not to Enforce Campaign Finance Laws. From the article:

“The Federal Election Commission is failing to enforce the nation’s campaign finance laws…The problem stems from three members who vote against pursuing investigations into potentially significant fund-raising and spending violations. In effect, cases are being swept under the rug by the very agency charged with investigating them.”

The op-ed quickly became Topic A of Thursday’s open meeting. As soon as the commissioners disposed of a routine agenda item, Republican Commissioner Caroline Hunter laid into Ravel.

“Should we investigate every 501(c)4 that makes [independent expenditures]?…you’re happy if someone is enforcing the law as you see it, not as it is written,” she declared, noting that the op-ed may confuse campaign finance lawyers about the Commission’s position.

Ravel refused to engage, saying she’d rather discuss her views with her colleagues in private.

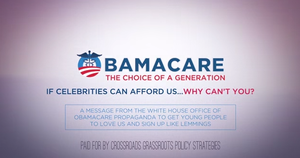

On the columns of the New York Times, however, the rookie commissioner minced no words. She labeled the three Republican members of the FEC as the “commission’s anti-enforcement bloc” and accused them of having turned a blind eye to the overtly political nature of a 501(c)4 nonprofit group, Crossroads GPS. The group spent millions helping Republican candidates and causes in 2010 — and continued to do so in subsequent cycles. But unlike traditional political committees, Crossroads — and many other groups modeled after it — are not required to disclose the sources of funding because they claim to be “social welfare nonprofits” for whom politics is not their primary purpose.

Four votes were needed to launch an official investigation into whether or not Crossroads broke campaign finance law but the Commissioners deadlocked on the vote. In their initial statement of reasons, Republican Commissioners concluded that “Crossroads GPS’s major purpose was not the nomination or election of a federal candidate,” but rather “issue advocacy and grassroots lobbying.”

As for the overall landscape of campaign finance in the post-McCutcheon world, the agency is still deliberating on the case’s impact. Commissioner Ellen Weintraub, a Democrat, expressed hope the decision would prompt the FEC to improve campaign disclosure. In an interview after she meeting, she told Sunlight that “the court has given us an opening to do more rule making and enhance transparency and disclosure in the system.”

Chief Justice John Roberts, in his opinion supporting overturning the aggregate limits, also emphasized the importance of real time disclosure of campaign contributions in “minimiz[ing] the potential for abuse” and noted that limits may have actually encouraged donors to give to dark money entities (like Crossroads). In the view of Sunlight, however, there remain substantial impediments to disclosure in spite of modern technology.