Transparency Case Study: Lobbying disclosure in Hungary

##Introduction

Lobbying regulation in Hungary provides a trenchant reminder that the political culture and the context in which reform is undertaken can have a profound impact on how a law is implemented — and whether it succeeds. The [Lobbying Act][1] was passed in 2006 as part of a larger government reform agenda, with very little policy consultation. When the new FIDESZ government came into power in 2011, the lobbying law was repealed because it was widely understood to be ineffective. The law has not been replaced.

When we began this case study research, [we noted][8] the importance of looking at failures along with successes, as they can provide rich opportunities to learn and improve future transparency interventions. In this case study, we pay particular attention to how and why the Hungarian lobbying regulation failed to provide meaningful transparency into interest advocacy and lobbying during the policy-making progress.

According to Petra Burai, head of research at Transparency International Hungary, the act was essentially “a policy transfer, and they copied best practices from all around the world” (8:00). Ms. Burai continued, “It was basically a copy-and-paste of the best practices but not taking into consideration how reality worked out in Hungary. … It was a strange phenomenon in a country that wasn’t ready to accept a regulation on lobbying” (10:00).

Our look at this ineffective policy provides some useful insights into how to think about crafting successful transparency policies:

– In the past, we at Sunlight [have][10] [written][11] [extensively][12] about the importance of [open and machine-readable data][13]. The lack of compliance in Hungary highlights that the format and processes of release matter very little if there is not quality data to be released in the first place. They are certainly related – but some minimal level of compliance must come first. – It is important not to under-estimate existing political culture. Hungary had a well established – albeit opaque – manner in which the private and public sector related. This process worked quite well for many powerful interested parties. Significant reform requires cooperation from these communities, and real sanctions to alter the incentives of actors. – To regulate professional lobbying, it is important for professional lobbying to be an integrated part of the political economy. This is not the case in Hungary. Because a lot of political influence in Hungary happened through personal interactions in ethical and legal gray areas, it was easy for all parties involved to claim that the lobbying law did not cover their behavior. – Achieving high rates of compliance in a law regulating a formerly unregulated gray market requires substantial political will, and a strong and independent enforcement body, neither of which were present in Hungary when the Lobbying Law was in effect.

For these reasons and others, the law never took hold effectively — and is a useful example of how well-meaning lobbying regulation can fail.

##Disclosure under the lobbying law The act [defines][14] lobbying as “The act or behavior of trying influence the decision-making process or expressing self-interests, based on a contract or conducted as business.”

The lobbying law [required][2] registration by individuals or third parties who contact the government to influence a decision on behalf of a client on a contract basis. Registrants were required to have a university degree, a clean criminal record and provide standard background and contact information. The law imposed reporting requirements on both lobbyists and public office holders, who were required to report activity – including the content and method of lobbying activity – on a quarterly basis.

The lobbying regulations also attempted to incentivize registration by offering special privilege to lobbyists upon registration. Registered lobbyists were granted a “hall pass” that entitled them enter government offices and formalized procedures for meeting with members of the national assembly, ministers, committees and other public servants (Fanny Hidvégi 4:00).

However, according to all of our interviewees, registration rates were quite low (Ádám Földes 44:00). According to Ms. Burai, “The main problem was everybody was kind of happy remaining in a gray area because they know the gray area and how to get around in that. … They were not really interested in passing the new law; not the government, not the business sector and, well, NGO’s are not really into lobbying per se because they had their own civic ways of interest [for example, advocacy]. (12:00)

Since the repeal of the lobbying law, the registry is no longer accessible online; however, an analysis by [Zoltan Pogátsa][3] found that while the law was in effect, “The database of lobbyists functions well, and is readily available online on the website of the Central Office of Justice without any password or special access privileges.” He continues by finding that “as of March 2010, some 248 individual lobbyists have registered themselves, along with 44 lobby organisations. Regular quarterly reports on lobbying are also readily available on the same website, with details of what kind of contact was made by whom with which specific civil servants in what specific matters.“

##Problems with registration and disclosure The dual public/private reporting responsibility over reporting activity was ineffective in practice.

Balázs Dénes, former executive director of the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union and now at Open Society, described his experience trying to get data disclosed under the lobbying law:

>You can argue if the law wasn’t perfect or it was a good one. One thing is sure, nobody took it seriously. Nobody filed those – in theory – mandatory lobby notes. … No one took this thing seriously. On the surface and level of slogans, of course. But when we tried to get some of those reports and somehow we never could achieve, we never could get any of them (17:00).

Our interviewees agreed that the activity that was disclosed in the registry (noted above) represented a very small fraction of those who were engaging in political influence activities. Under the lobbying law, the vast majority of influence activity continued to be done by non-registered lobbyists in a non-transparent way. According to Petra Burai, those who did register and lobby under this system were those who already “really did their job quite openly and did the government affairs and government relations anyway, so they thought that it would be an advantage to them. For example, those public affairs firms and lawyers, those were the typical ones to register.” She continued on to note that, however, because there was no strong incentive,”no sanction system that was operating, they dropped out quite early” (20:00).

>So they didn’t write reports or [those] who wrote the reports or weren’t really happy about the feedback or the feedback that they never got or that they were sometimes neglected because of being registered lobbyists. So there were some public affairs experts who told me that they were basically neglected for being the lobbyists and they recognized all of this because nobody wanted them at the meeting (Burai 20:00).

Ádám Földes, an advocacy advisor with Transparency International, expanded on this issue, noting that the only person he recalled who consistently registered:

>was an individual … an anti-tobacco activist that doesn’t really have a CSO. Because he influences or tried to influence public decisions, though he’s not required to register, he registered and reported on his meetings. That was the only thing I remember where I could see any meaningful information on concrete pieces of legislation. … For the rest, even if they were registered, they always reported that they there was no lobbying activity and there was nothing to report (46:00).

It is, of course, difficult to prove what kind of lobbying activity was happening but going unregistered. However, when looking at archived lobbying registry data prior to our interview, Ms. Hidvégi, head of Data Protection and Freedom of Information at the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union, found “that no really big companies were a part of such conversation. For example, there was no energy company in the registry” (20:00). Dr. Tóth noted in a [study][14] that essentially the entire construction and financial sectors were also absent from the registry as well.

##Political culture

In large part, the failure of the Hungarian lobbying registration and disclosure system can be attributed to an unfavorable political culture for lobbying transparency and a lack of political investment in the law’s success.

Ms. Burai noted that ”lobbying had no real tradition in Hungary,” and that, while interest-based advocacy has of course always existed, “it’s tradition, whereas lobbying is a recognized profession or a way of making policy or channeling interests that was not accepted” (8:00). Instead, in Hungary, “Lobbyist and lobbying are kind of a negative terms. So when we think about lobbyists or usually people talk about lobbyists there is some kind of negative connotation. Those experts who do the actual lobbying work, don’t really like to call themselves lobbyists at all” (4:00). People engaged in influencing policy tend to refer to themselves as public affairs experts. When Ms. Burai was researching the implementation of the lobbying law for Transparency International, she said, “When I started to track them or we started to track down lobbyists, we basically had to go to PR firms and in PR firms we found public affairs experts who were kind enough to talk to us and share their experiences, but even they were not a bit happy to call themselves lobbyists” (6:00).

In contrast to the United States or Canada, where formalized and relatively transparent professionalized lobbying is a well understood part of the political economy, Hungary has historically operated – and continues to operate — largely through informal connections. Földes expanded on this point in great detail in our interview. He noted:

>It’s a rather important part of business that everybody has connections. Everybody knows who is who, went to the same school, same university. There are relations everywhere. … If you make business with the state, like trying to take part in public contracting, public procurement, then you also need the decision-makers in the state. Either for legislation or for public contracts, you need a good relation with them, and as the corruption is quite high, any business has to find its way to the decision-makers.

>If it goes everything through an informal channel, the main thing that matters is there is trust between the public decision-maker and, let’s say, a private company or CEO of the company, and what they care about that they agree. It may be corruption or it may not be corruption, I would say there is a big gray zone. There, it’s quite clear they don’t want to disclose anything about that.

>For the illegal part, it’s clear. For the legal part, it’s just reputation risk, I would say, and why to make it public if there are no strict rules to make it public. The same for the public administration side, it’s not Scandinavia where the public administration has a tradition of being open (28:00 – 32:00).

However, rather than “professional lobbyists try[ing] to influence lawmaking, it turned out it’s more usual that, for example, the CEOs of companies do lobbying themselves” (Földes 8:00). So when it came to compliance, many people engaged in interest advocacy did not really think of the law as applying to them, especially since it was explicitly drafted to focus on a set of registered lobbyists.

As for public officials, compliance with the lobbying registry was also viewed as unimportant and burdensome. Ms. Hidvégi, noted that “public servants saw this only as an administrative task. It feels that they didn’t even see the aim of these provisions and why they had to do it, so they just avoid it as other administrative tasks. As you know, they can be very annoying.” On top of that, there was no training offered to public officials as the law was implemented. She added that “they were not trained on lobbying or how to handle these companies or what should they do when they are being contacted. It was a mere administrative barrier for them” (22:00).

Public office holders were put in a position where complying with the law felt like merely an administrative burden. On the other hand, in a political culture still very much reliant on personal relationships and trust, revealing who they were meeting with came with real downside risk to their careers and future. Petra Burai summarized this effect on public officials during our interview:

>Whether sensitive information goes out, what they can talk about, what they can’t talk about, and whether they write the report of the whole meeting and somebody can’t just knock on their head and say hey, you shouldn’t have said that or you had no entitlement to decide on that or being influenced about that. So it’s kind of a psychology of being a public official, you never know whether you are entitled to do something or you are not. And the easiest way to remain in a secure position when those meetings are hidden or secret so nobody can know what’s really said and how you are influenced or the way you are not influenced.

>So it takes courage to admit how you deal with lobbyists and whether you deal with lobbyists at all because that was the issue. We never knew that. You have to understand how government works or governmental official works in that way (16:00).

Unfortunately, compliance by public officials was quite low. Many ministries did not comply with their mandate to appoint leaders who were designated to accept registered lobbyists, nor did they routinely publish reports indicating the lobbyists who had contacted them, as the regulations required. Rather, “In most situations they had to decide whether it is more dangerous to give out information that they were talking about — and this is kind of a dangerous situation for them — or not to write the report” (Burai 16:00). Ms. Hidvégi commented that, “It’s not the easiest way to convince public officers that they have to act transparently. And this is not just a lobbying issue. … They still take them as a favor to answer, not an obligation” (7:00). [edit June 30 5:10pm: the above quotation from Ms. Hidvégi was originally mis-attributed to Ms. Burai]

##Civil society engagement

Hungary has a mature and robust civil sector, and the organizations we spoke with were eager to use the information that should have been disclosed under the lobbying law. However, none of them were able to find any usable data. Földes best summarized the experience of trying to use the lobbying registry working as a watchdog:

>Whenever we were interested in who has a little bit on what, I could hardly find any meaning for any useful piece of information in that database. There was no voluntary observance of the law, so neither side took this law seriously and the department [Central Office of Justice], their oversight didn’t really have the means to enforce it. It was not very useful for a watchdog NGO because there was practically nothing useful in the database (26:00).

Ms. Hidvégi explained that even when the law was in effect, trying to find out anything about who was influencing policy was “more like an investigative journalism activity, and try to find something in the dark, but the revealed information is not enough for anything” (34:00). However, whenever watchdogs would go to ministries to ask about the lobbying activity reports that they were supposed to be filing, they were told “’No, we didn’t have lobbying activities here’” (Lederer 18:00).

Civil society was widely involved in criticizing the law, and offering substantive suggestions for reform and strengthening its implementation — but they quickly learned not to expect to find any meaningful information in the registry itself.

##Enforcement powers The Central Office of Justice was charged with control over the registry, and, according to Ms. Burai, it was not “independent in a way they could have imposed anything.” She continued, “They could have demanded [compliance], but they were not powerful enough to impose sanctions. Not to those who weren’t really submitting the reports. Basically, it was that they were really, really powerless institution“ (23:00).

According to Dr. Ernő Tóth’s [research][14], this office was supposed to have a coordination role only, with a specific focus on helping centralize the reporting that was to take place in a decentralized fashion across various agencies. Dr. Tóth, who worked inside the Office of Justice as the law was implemented, [argued][14] “since in Hungary lobbying has had no previous history and there was no strong ecosystem of lobbying transparency, the enforcement agency should have given much stronger investigative roles and powers.”

So far we have seen that the Hungarian lobbying law creates incentives in which both lobbyists and public officials see little upside potential, and high downside potential, to compliance. Compliance cost them in terms of decreased effectiveness and loss of trust in the largely informal and personal world of interest advocacy.

The law provided neither strong enough positive incentives to induce registration, nor strong enough sanctions to make failure to register a real concern. Ms. Burai explained that the law was:

>too harsh in many ways to them because there were no incentives for those who registered as lobbyists. So there was no extra given. When you are transferred, then you are good enough to make your reports, write your reports, submit what you’ve done in the year and stuff like that. So there were no incentives and positive consequences when you work good. On the other hand, there were no sanctions either. According to the law, there could’ve been fines incurred if somebody breached the law. I think the maximum amount was 10 million forints and I think that should be ~$45,000. But never was a fine imposed. Nobody used the law, it’s tough and that’s one of the reasons they said it was easier to stay hidden because there was no use in the law (12:00).

One of the major penalties under the law was forbidding a lobbyist who failed to comply from registering the following year. In a system where registration was already quite low and most interest advocacy still happened outside of the channels of registered lobbying activity, this was not a meaningful threat. Additionally, Dr. Zoltán Pogátsa [noted][3] in a report for Europeum that “a maximum penalty of ten million forints ($45,000 USD) for non-registered or inappropriate lobbying can hardly be a deterrence when a the potential profits at stake might be measured in billions, or even tens of billions of forints.”

Sandor Lederer, the CEO of K-Monitor, concluded that “the biggest issue was that there were no real sanctions and that’s why nobody was afraid of having any problems with doing illegal [lobbying activities] or not register[ing] for lobbying activities. Nobody talked about any other aspect of the law because it wasn’t obvious from the beginning that it won’t really work. It was more to show that we have such law, that it did something against corruption or we did something for the transparency of lobbying, but really it was not used by anybody” (10:00).

None of our interviewees were familiar with any cases where sanctions occurred under the lobbying law.

Mr. Pogátsa has [highlighted][3] a few additional ways in which the lobbying act – even as it is written – does not provide adequate sanctions to enforce compliance. In particular, there are no sanctions on public officials for failing to file quarterly reports about which lobbyists approached them, nor does it sanction officials for not reporting non-registered lobbyists who approach them. As a result, failure to register as a lobbyist is not a significant barrier to accessing to public officials.

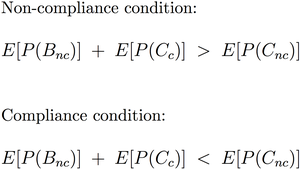

##A simple formal model of lobbying compliance We propose the following simple formal model to help explain the failure of lobbyists to comply with the Hungarian lobbying law.

In this model *E*[*P*(*Bnc*)] is the expected direct benefit of non-compliance (*Bnc*). *E*[*P*(*Cc*)] is the expected value of the cost of compliance (*Cc*) — the avoidance of which we treat as an indirect benefit of non-compliance — and *E*[*P*(*Cnc*)] is the expected value of the cost of non-compliance (*Cnc*).

Essentially, this formalizes the hypothesis that when the net expected benefits of non-compliance (on the left-hand side) exceed the net expected costs of compliance (on the right-hand side), the default expectation is non-compliance. When this inequality is reversed, and the net expected benefits of non-compliance are less than the net expected costs of non-compliance, we expect actors to tend towards compliance.

Unpacking the components can clarify its applicability to the Hungarian lobbying case. The left-hand side (LHS) of the equation describes the net expected benefits of non-compliance. The first term on the LHS is the expected direct value of the benefit of not complying with the lobbying disclosure regulation. This expected value is quite high under current circumstances in Hungary, because interest group advocacy and influence primarily occurs through informal channels that do not comply with regulations. The second term on the LHS, which represents the expected costs of compliance, is also quite high in Hungary. This covers costs like hiring extra staff to meet reporting requirements and potential lost business because risk averse public officials are loath to meet with registered lobbyists. As our interviewees indicated, the cost of complying with reporting requirements is a significant concern for interest advocates, and registering may make lobbyists less effective.

The net expected benefit of non-compliance (the LHS) is the sum of these first two terms, the expected direct value and the indirect benefit of avoided costs.

The right-hand side of the equation (RHS) represents the expected value of the costs of non-compliance. We can understand this as the probability of getting caught in violation of the law multiplied by the severity of the penalty for violating the law. As our interviewees indicated, investigation was rare-to-non-existent, and the sanctions were quite low, relative to the benefits.

In short, this means that our best estimate is that both terms on the LHS of the inequality are rather large, while the term on the RHS is vanishingly small. This leads us to conclude that in the Hungarian context, non-compliance is the simple equilibrium position.

This highlights several potential levers for reform. Reform could focus on decreasing the value of the LHS (i.e. making compliance less costly) or increasing the value of the RHS (making non-compliance more costly) or both.

On the LHS, this could mean lowering the benefit to non-compliance, perhaps by making it harder for non-registered lobbyists to meet with or do business with politicians. This could also mean decreasing indirect costs by making compliance cheaper by streamlining the administrative burden and providing additional incentives and access to registered lobbyists. Increasing the value of the RHS could include both strengthening sanctions or vesting an independent agency with real investigative authority, which would increase the likelihood that violators are caught. Either of these would lead to an increase in the expected cost of non-compliance.

##Conclusion

The lobbying law in Hungary was brought into force in a situation where there was no established culture of professionalized lobbying, and where public officials and lobbyists had strong incentives to keep influence peddling in the shadows. Absent strong intervention to change the cost/benefit payoff of these actors, it was unreasonable to expect change.

Petra Burai offered an important insight on establishing a more effective lobbying regulation regime in Hungary:

>First the recommendations had to be advocated because everybody has to be convinced that the lobby is necessary thing and it’s not something unnatural or natural evil or something like that that’s going on. Lobbying is good. Lobbying is acceptable and it is necessary for policy process. If you are doing it in a way that is transparent and accountable enough, it’s not what people would trust. I guess that’s the most important thing what we had as an outcome. Of course, the practical side is that the old act was not really effective to solve or effective enough. That has to be addressed as well (38:00).

Only once an established tradition of professionalized lobbying is in place can it be effectively overseen. Otherwise the infrastructure and practice of off-the-books, non-registered lobbying is so common-place that registration and disclosure will ultimately lead – as it did in this case – to effectively empty registries. The Hungarian case reminds us that policy reform cannot overcome the constraints of political culture unless it is crated to effectively alter the incentives of the key actors of those to whom it will apply.

##Supporting materials

###Ádám Földes Advocacy Advisor, Transparency International

[Download interview transcript here.][4]

###Balázs Dénes Director, European Civil Liberties Project at Open Society Foundations

[Download interview transcript here.][5]

###Fanny Hidvégi Head of Data Protection and Freedom of Information Program, Hungarian Civil Liberties Union

[Download interview transcript here.][6]

###Petra Burai Head of Research, Transparency International Hungary

[Download interview transcript here.][7]

###Sandor Lederer Co-Founder and CEO, K-Monitor

[Download interview transcript here.][8]

[^1]: Source: http://www.kimisz.gov.hu/data/cms24433/A_lobbitorveny_es_a_lathatatlan_lobbi_tanulmany.pdf Translation by Júlia Keserű.

[^2]: *ibid.* Translation by Júlia Keserű.

[1]: http://www.complex.hu/kzldat/t0600049.htm/t0600049.htm “2006th XLIX. law ‘Lobbying Act'” [2]: http://www.complex.hu/kzldat/t0600049.htm/t0600049.htm#kagy5 “Registration requirements” [3]: http://www.europeum.org/doc/pdf/pogatsa_HU.pdf “Zoltan Pogatz. 2011. THE LAW ON LOBBYING IN HUNGARY, AND ITS EFFECTS.” [4]:http://sunlight-embed.s3.amazonaws.com/2014/Hungary_Transcripts/Ádám%20Földes.docx [5]:http://sunlight-embed.s3.amazonaws.com/2014/Hungary_Transcripts/Balazs.docx [6]:http://sunlight-embed.s3.amazonaws.com/2014/Hungary_Transcripts/Fanny.docx [7]:http://sunlight-embed.s3.amazonaws.com/2014/Hungary_Transcripts/Petra.docx [8]:http://sunlight-embed.s3.amazonaws.com/2014/Hungary_Transcripts/Sandor.docx [9]:http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2013/02/12/whytransparencymatters/ “Why Transparency Matters” [10]:http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2013/08/12/case-study-public-procurement-in-the-slovak-republic/ [11]:http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2013/10/07/case-study-public-procurement-in-the-philippines/ [12]:http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2014/02/03/case-study-public-procurement-in-sydney-australia/ [13]:http://sunlightfoundation.com/procurement/opendataguidelines [14]:http://www.kimisz.gov.hu/data/cms24433/A_lobbitorveny_es_a_lathatatlan_lobbi_tanulmany.pdf “translated by Júlia Keserű”