OpenGov Voices: Transparency needed on corporate subsidy spending in the U.S.

Last week, Nevada announced it was granting Tesla Motors $1.3 billion in subsidies for the construction of a new lithium-ion battery production facility near Reno. The massive subsidy package includes exemption from the state sales taxes for 20 years, exemption from property and payroll taxes for 10 years, discounted electricity rates and infrastructure assistance.1 The new facility is expected to create 6,500 new jobs, resulting in a cost of $200,000 per job – if all job creation targets are met.

The Tesla Motors deal made headlines across the country, but the extent of state corporate subsidy spending remains unclear. Several organizations have attempted to bring corporate subsidies to light. In a special report, the New York Times finds that states spend about $80 billion per year in subsidies to private businesses.2 Good Jobs First, a non-partisan organization that brings together all publicly available data on corporate subsidies, finds an average of $12.7 billion per year in subsidies.3 The gap between the New York Times estimate and the Good Jobs First data suggests that the majority of subsidies remain out of the public view. The gap is due in part of states not making spending data available. In the Good Jobs First database, the most comprehensive available, almost no data on subsidy spending is available for Wyoming or Hawaii. Other states report only large subsidy packages found in the news (South Carolina, Tennessee) or only a few of the incentive programs they offer (Alaska).

Also in need of transparency is whether subsidies actually achieve their stated job growth and investment goals. Subsidization is often justified by lawmakers as a means of creating quality jobs. Of the 127,000 + subsidies awarded from 2006-2013, only 49,455 also reported the estimated number of jobs to be created.4 Whether or not the job creation estimate was achieved is not available in any systematic way. This makes it incredibly hard to assess the effectiveness of economic development policies. It also keeps relevant information away from voters, who could use the information to hold elected officials accountable at the ballot box. In the case of Nevada and Tesla, Republican Governor Brian Sandoval estimated an 80:1 return on investment.5 To assess whether this goal is reached requires regularly updated data from the state and business which at this point does not exist.

The politics behind corporate subsidies is also in need of exposure. In a recent study, Virginia Gray and I find that states increase their subsidy spending the more candidates receive in campaign contributions from businesses.6 Campaign contributions do not buy subsidies, but they are used to gain access to legislators and promote subsidies as being in the public interest. The relationship holds even when controlling for other economic and political explanations, such as the unemployment rate or competition with neighboring states.

The relationship between business and state government needs to be more transparent. The fact that states give more to business when business gives more is troublesome, especially since citizen groups and labor unions are much less well funded and organized. In order to explore this relationship further, the Sunlight Foundation’s data on campaign contributions could be merged with data on corporate subsidies. Subsidy data should be regularly updated and work to uncover much of the spending currently unavailable to the public. Merging the two sets of data enables tracing a line between an individual business’ contributions and the subsidies it receives from government.

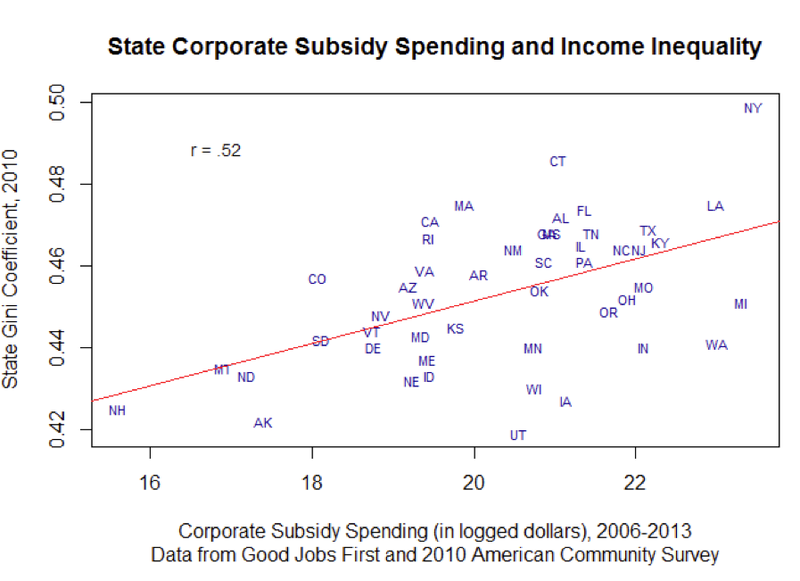

Ultimately, subsidy politics, spending and efficacy need to see the light of day because subsidies fundamentally affect the way the economy works. Subsidies work to shape economic behavior by incentivizing job creation in certain sectors and business location decisions. Subsidies also result in the loss of revenue, which limits the resources states have to spend on public welfare and education programs. Furthermore, subsidies go disproportionately to the largest firms, which could isolate them from competition in the market place and concentrate wealth among the relatively few. The graph below shows a strong, positive correlation between corporate subsidy spending and state income inequality (measured by the Gini coefficient). While the reader should caution themselves that correlation does not equal causation, the relationship suggests further investigation of subsidies is needed as more and more public dollars go to the largest businesses. Greater transparency on corporate subsidies will enable Americans to be more informed on economic politics and policy, helping to strengthen policy and hold elected officials accountable for their decisions.

—–

1 Wald, Matthew L. 2014. “Nevada a Winner in Tesla’s Battery Contest.” The New York Times.

2 Story, Louise, Tiff Fehr and Derek Watkins. 2012. “United States of Subsidies.” The New York Times.

3 Calculated by author using Good Jobs First Subsidy Tracker data for 2006-2013 http://www.goodjobsfirst.org/subsidy-tracker

4 The 127,000 observations include only observations with a reported subsidy value, itself a subset of all subsidies. Numbers calculated by author using Good Jobs First Subsidy Tracker data http://www.goodjobsfirst.org/subsidy-tracker

5 Sonner, Scott and Justin Pritchard. 2014. “Nevada offers Tesla up to $1.3B for battery plant.” The Associated Press.

6 Jansa, Joshua M. and Virginia H. Gray. 2014. “The Politics and Economics of Corporate Subsidies in the 21st Century.” Paper presented at Annual Meeting of American Political Science Association in Washington, DC, August 28-31.

Joshua Jansa is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Political Science at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. His research interests include interest groups, state politics, economic policy and political and economic inequality. Please visit his website for more information.

Interested in writing a guest blog for Sunlight? Email us at guestblog@sunlightfoundation.com