Using open data to stimulate new methods of human rights monitoring

The traditional strategy of monitoring human rights violations goes like this: Local and international human rights groups often focus on legal advocacy, representing the victims of human rights violations who are willing to testify in court. Resources are then allocated toward conducting interviews, gathering personal testimony and evidence for court, which is primarily anecdotal, to bolster these cases. Data science doesn’t always seem to fit neatly into this narrative, so the potential open data may have in supporting human rights monitoring hasn’t been fully explored. As we’ve laid out in our previous post, there are potential limitations and benefits to using open data to monitor human rights. Throughout this post, we will identify ways that open data can enhance human rights litigation, as well as explore examples where open data could inspire alternative methods for human rights monitoring.

Data cannot replace personal testimony in courts, but it can bring more detail to legal briefs and provide evidence to enrich human rights legal cases. Supplementing traditional interviews, personal testimony with reliable data could make for a clearer picture and more compelling evidence to help put these claims in context. The UN Dispatch has highlighted the important role that data analysis has played in several war crime prosecutions, helping to provide concrete and vivid evidence to hold perpetrators to account.

Organizations, such as the Human Rights Data Analysis Group (HRDAG), are incredibly valuable resources in supporting these ends by applying data science to the analysis of human rights violations globally. HRDAG was founded in 1991, after its founder compiled and cross-referenced databases on the victims and perpetrators of violence in El Salvador during its civil war. The database helped identify nearly 100 officers who were involved in some of the worst atrocities during the war. Since then, HRDAG has used data analysis to support a variety human rights legal cases. For example, the organization mined through data on migration patterns during the 1999 conflict between Yugoslavia and NATO to undermine claims that the mass migration of Albanians from Kosovo was a result of NATO bombs. HRDAG ultimately concluded that the migration was the result of a systemic effort by the Serbian military to “cleanse” the region of Albanians. This analysis was submitted to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia to support the case against Slobodan Milošević for genocide and crimes against humanity.

Good data analysis by human rights groups to help bolster litigation cases may not be a new concept. However, what is new is the worldwide movement to use technology to provide free and open access to the data that governments and the public possess. This unprecedented access to data provides the opportunity for data to be used more widely and effectively in these cases. With increased access, data can be open to analysis by a larger range of actors, including a variety of local human rights groups. The verification of others can help mitigate bias. When only a few select people have access to the data, it is much easier to paint a subjective picture within a court of law.

Outside the traditional framework of litigation and policy advocacy, are there ways that data can advance human rights issues? Data may provide additional pathways to raise awareness to human rights issues by describing a vivid story and sparking grassroots advocacy initiatives while grounding these issues within a local context rather than relying so heavily on international initiatives with a Western lens.

Indices, such as the Freedom in the World Index, released annually by Freedom House, have become a measure for whether countries are adhering to these recognized treaties and declarations and are often used to raise awareness of the state of human rights globally to the public and media. However, indicators like these are frequently criticized for being Western-biased and arbitrary. As Foreign Policy recently noted, they continue to be taken seriously because: “Unlike the number crunchers, Freedom House knows how to tell a story. And in the world of international human rights advocacy, one good story is worth a thousand finely tuned disaggregated indicators.” Essentially, when most people don’t have the time or resources to decipher the nuances and limitations of serious data science, some level of simplification and theatre help the issue get some attention.

Despite the belief that data is both too complicated and dull to interest the public at large, data can fill this void while simultaneously helping to eliminate some of the biases, simplifications and methodological flaws of international monitoring mechanisms. For example, human rights groups could take a play from data journalism’s book, combining both a compelling narrative of an individual and using data to frame the context within that story has happened. Setting the stage in this way is crucial — as Eva Constantaras, a data journalism trainer at Internews, has repeatedly stated: “People don’t care about data. People care about people.”

When using data to tell a story, analysis, visualization and reporting can play a huge role in stimulating grassroots engagement campaigns or legislative policy advocacy. The end result can present an opportunity to utilize these strategies to monitor human rights. We’ve compiled some examples where open data, including government data, has been used in nontraditional ways to monitor human rights violations, to engage the public in the topic and even to stop human rights violations as they are happening.

—–

Gender Inequality and Corruption in Kosovo, Open Data Kosovo

- Open Data Kosovo conducted data analyses to draw conclusions about the relation between gender equality in the workforce and corruption. A large part of the series focused on women’s equality in the workforce, concluding that the participation rate for women in the workforce in Kosovo is one of the lowest in the world, and more women are leaving the workforce than before.

- Human rights issue(s): Right to work and equal right to participate in the work force

- Data sources: Kosovo Agency of Statistics Labor Force Survey; World Bank Gender Statistics

Gender Wage Gap Game, JumpStart Georgia, Georgian Trade Union Confederation, Center for Social Sciences at Tbilisi State University and New Media Advocacy Project

- This interactive game uses official data from the Georgian government on wages, wealth and labor to personify how women are discriminated against in the workplace and ultimately suffer financially compared to men. They also created a data explorer that allows you to explore raw data from a survey from the Center for Social Sciences on perceptions of gender discrimination in the workplace.

- Human rights issue(s): Right to work and equal right to participate in the work force

- Data sources: Georgian government; Center for Social Sciences, Tbilisi State University

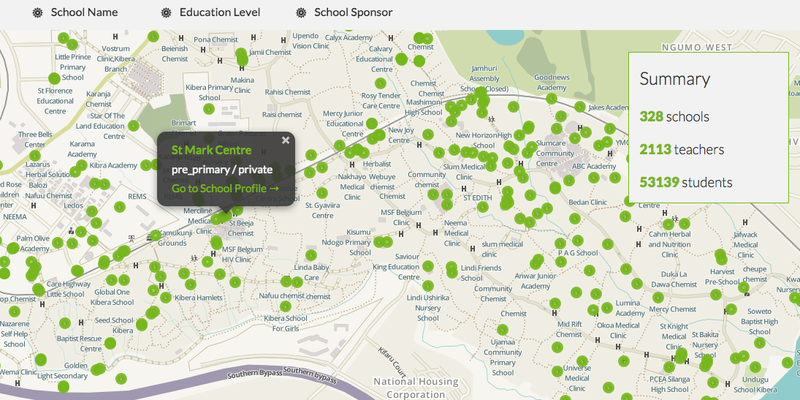

Open Schools Kenya, Map Kibera Trust, GroundTruth Initiative and Development Gateway

- Open Schools Kenya combines OpenStreet Maps, data released by the Kenyan government supplemented with citizen-collected data to map schools in Kiber, one of the slums of Nairobi.

- Human rights issue(s): Right to education

- Data sources: Open Street Map; crowdsourced citizen data; Kenyan government data

Cadasta Platform, Cadasta Foundation

- The Cadasta Foundation is aggregating property administration data and mapping property into an open source platform.

- Human rights issue(s): Right to an adequate standard of living; Right to culture

- Data sources: Official government data; OpenStreet Maps

Crisis Text Line, Crisis Text Line

- Crisis Text Line is a service that connects those who are distress with trained volunteers to support them in their time of need. Crisis Text Line takes data that it collects and shares it with researchers to help provide better services relating to suicide prevention.

- Human rights issue(s): Right to health and a healthy environment

- Data sources: Crisis Text Line Open Data Collaboration