Why has lobbying grown and made DC rich?

The news that seven of the ten highest income counties in the U.S. are in the Washington, DC area has prompted Wonkblog’s Dylan Matthews to investigate why the DC wage premium has grown. In digging through the data, he finds that the growing wage premium correlates most closely with growth of lobbying spending that “The rise of influence-peddling more broadly, more than just lobbying, is likely what’s driving this correlation.” Sounds quite probable to me.

Ross Douthat is likewise convinced that DC’s increasing wealth comes “from the growing armies of lobbyists and lawyers, contractors and consultants, who make their living advising and influencing and facilitating the public sector’s work.” And Matt Yglesias, with a nod to Will Wilkinson, believes that “the area’s rising affluence seems clearly to be linked to the rising investment in influence peddling that characterizes American politics and the economy”

All of this begs the question, however, as to why lobbying would have taken off now, in this last decade or so? This was the question that I tackled in my Ph.D. dissertation (and soon, ahem, eventually, book).

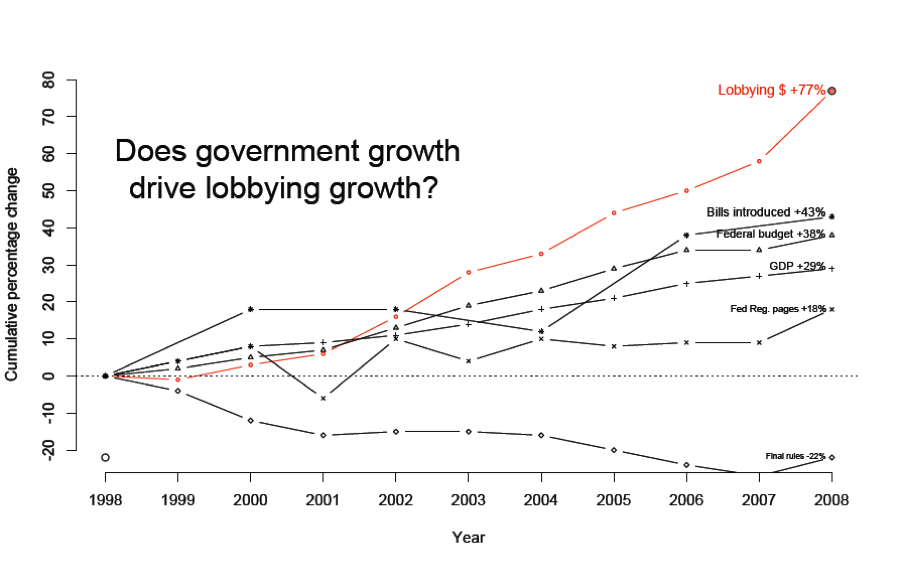

I started with the obvious question that the bloggers have picked up on. I soon realized that, yes, government was part of the story, but not really the whole story. Lobbying was growing faster than government. And the serious growth of lobbying has picked up only in the last 10-15 years, while government has been growing (and much has been at stake) for a long time.

I pull the following chart from my dissertation to illustrate:

Lobbying was growing faster than any measure of government size or the economy I could find. But why?

The short answer is that over the last two decades, corporate America came to see the value of politics and learned to play the Washington game.

Washington lobbying is a lot like the Hotel California.

Companies come to DC for any number of reasons (a regulation they don’t like, a subsidy they want, etc.). Often anti-government managers are skeptical of the value of getting involved in politics, viewing politics as a messy and costly business.

But once they hire lobbyists and set up lobbying offices and become active in trade associations, they start to see the benefits of political participation. Lobbyists are there to point out new potential opportunities and new threats, and to make the case that being engaged politically is good for the bottom line. Companies get involved in more issues and more ongoing battles. And once they’ve paid the start-up costs of learning about Washington and building relationships, the cost-benefit equation of being politically engaged shifts even more in favor of staying and doing more.

That’s why by far the strongest predictor of how much a company will spend on lobbying is how much it spent on lobbying the year before, far more than what’s on the agenda or any other metric of government activity. Lobbying has a self-reinforcing dynamic. Once companies come to Washington, they stick around, and usually expand. And with each passing year, more companies come to Washington.

There is also certainly something to the arms race theory that Matthews mentions, referring to Baumgartner et al.’s excellent study, Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why, which finds that changing the status quo is rare and hard, and more resources do not consistently translate into higher probability of success.

Without a doubt, there are many issues on which, in classic arms race fashion, two well-funded sides fight to a draw, both drawing tremendous resources into Washington. But on many other issues, there is no arms race – only many well-paid lobbyists working the ins and outs of highly technical issues whose mind-numbing details are a dull soporific to anybody without a direct financial stake in them. See, for example, the miscellaneous tariff bill. Or the tax code, for that matter.

The big point is that lobbying creates its own demand. The reason that lobbying has grown (and will likely continue to do so) is only partly because of objective conditions (e.g. size of government, regulatory environment). It is more the manifestation of a shift in how corporate America understands the value of Washington lobbying. It is a shift in good deal brought upon by Washington lobbyists themselves, who are often just as adept at convincing corporate managers of the value of their services as they are of convincing members of Congress of the rightness of their cause. If not more so.