How much lobbying is there in Washington? It’s DOUBLE what you think

Tim LaPira, an Assistant Professor of Political Science at James Madison University, is a Sunlight Foundation Academic Fellow.

With the help of the lobbying industry, Washington’s regional economy seems to have weathered the economic storm of recent years. Curiously, though, the seemingly simple question “How much lobbying is there in Washington?” is surprisingly hard to answer. After Congress passed the 1995 Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA), which ostensibly required all “lobbyists” to report their activities on behalf of paying clients, the answer should be a no-brainer: just find the legally-mandated disclosure forms, and count them up. The Center for Responsive Politics, with support from the Sunlight Foundation, has been doing this (well!) for years.*

The problem is that just about everybody in the influence world knows that these numbers fall way short of reality. You might even say “under-the-radar,” “stealth,” or “shadow” lobbying is a bit of an Open Secret in Washington. What we don’t know is just how many shadow lobbyists there are.

The reason for the lack of transparency is clear: the LDA definition of “lobbyist” is too narrow. If lobbyists want, they can fully comply with the law and do virtually the same influence-for-pay as strategic policy consultants or historical advisers, and choose not to disclose. Even lobbyists themselves seem to find little meaning in the term “lobbyist.” The American League of Lobbyists even dropped the word “lobbyist” from their name to officially become the Association of Government Relations Professionals.

Estimating the Actual Size of the Lobbying Industry in Washington

So, to try to get a better estimate of how many lobbyists “government relations professionals” there are, my collaborator Herschel Thomas and I did the next best thing: we bought the lobbyist phonebook. We drew a random sample of people listed in Lobbyist.info, then had student assistants consult a variety of online sources to determine where they used to work (especially inside the federal government) and what jobs they have now.

We found that about half of those involved in policy advocacy—our all-of-the-above term for people in the private sector getting paid to influence public policy, regardless if they meet the strict LDA definition of “lobbyist”—did NOT report lobbying activities in 2012 (52.3%, ±5.1% at the 95% confidence level). That is, for every one lobbyist who does the public the favor of disclosing his or her activities, there is one shadow lobbyist listed in directory who does not.

If we assume that the cost of reported and stealth lobbying is the same—that every one person accounts for an unweighted average of about $270,000 in lobbying influence per year—then we estimate that in the calendar year 2012, organized interests spent about $6.7 billion “relating” with the government.

Let’s put that number in perspective: For every one member of Congress, the influence industry produces about $12.5 million in lobbying. By comparison, the average 2012 budget for member of the House of Representative’s office was only $1.3 million. So, in 2012—a presidential election year, in a down economy, during arguably the least productive Congress ever—“government relaters” accounted for more than nine times the typical House member’s official operating expenses.

What’s more, the one-year $6.7 billion tally is about $500 million more than all the campaign money spent on the record setting 2012 election cycle. So if we multiply the one-year lobbying industry estimate by two years, then the relatively non-transparent lobbying industry inside the Beltway generated about twice-plus-$1 billion more in 2011 and 2012 than the relatively highly regulated campaign finance system that influences politics outside the Beltway.

Who Discloses, and Who Does Not?

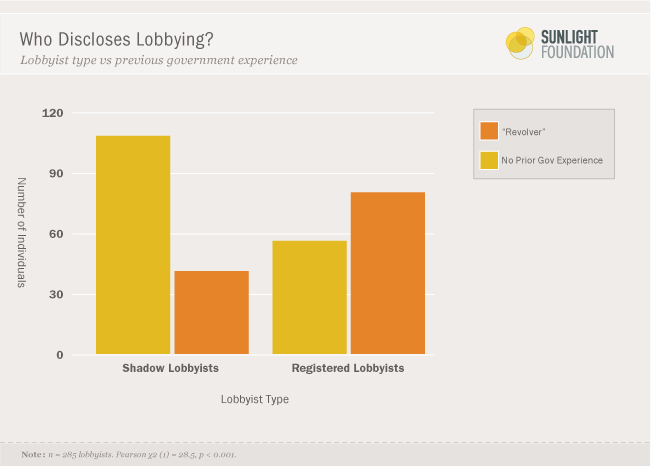

This is not exactly an easy question to answer because, well, half of these professionals don’t disclose what they’re up to. But, we can make some general inferences based on where they used to work. To do this, we simply categorize them into those who’ve gone through the revolving door, and those who haven’t.

Revolvers (lobbyists who worked inside the federal government) are more likely to disclose their lobbying, though 41% still choose to hide it. On the other hand, conventional lobbyists (those who were never on the federal payroll) are much more likely to be opaque about their influence activities.

Which begs the question: Why are revolvers more transparent? Again, we can’t say for sure because we don’t have good, publicly disclosed data on the kind of influence activities these people are engaged in now. So we look more closely at where they used to work in the federal government for some clues.

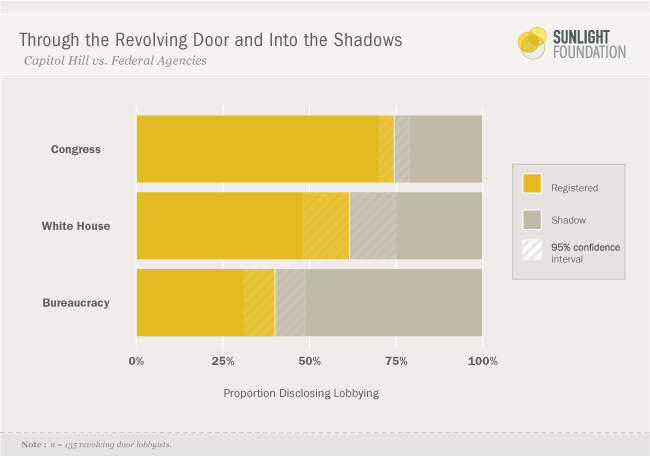

Among revolvers only, those who previously worked in Congress were much more likely to file lobbying disclosure reports (z = 3.6, p < 0.001). But, those who worked in bureaucracies in the executive branch are much less likely to do so (z = -3.5, p < 0.001). Apparently, not only is the legal term for “lobbyist” insufficiently narrow, there is little consensus on what it means to be a lobbyist, especially between those who worked on Capitol Hill versus those who worked in a federal agency.

The take away: it’s “lobbying” if lobbyists are lobbying on Dodd-Frank when it was just a bill in Congress, but it’s “not-lobbying” if lobbyists are lobbying on Dodd-Frank when it is a proposed regulation at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Or the Treasury Department. Or the SEC. Or the FDIC. Or the Fed. Or, if they’re lobbying on the thousands of other regulations proposed by federal agencies every year.

Combine the semantic confusion of what it means to be a “lobbyist,” the “Scarlet L” stigma associated with what is an otherwise ethical profession, and the disincentives of the Obama administration’s rules against lobbyists working in the administration, we end up with less—not more—transparency about lobbying in Washington.

Bottom line: it’s needlessly hard to figure how much lobbying there actually is in Washington. Now, only if we could get somebody to relate that idea to Congress…one step in the right direction would be to support the Lobbying Disclosure Enhancement Act, which would close the loophole that shadow lobbyists use to avoid disclosure.

Graphics by Amy Cesal and Alexander Furnas.

* In the interest of full, ahem, disclosure: LaPira was the researcher responsible for editing the OpenSecrets’ Lobbying Database from 2005-2007.