Foreign lobbying regulation: A history

The Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) has had a long — and spotty — history.

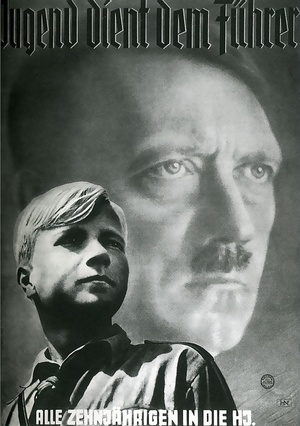

Pushed through in 1938 by the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, it was intended to help blunt what authorities here believed was an intensifying propaganda blitz by Germany.

The aim of the legislation: To make it easier for federal counterespionage authorities to keep tabs on U.S.-based individuals and other groups helping to drum up support for the Nazi movement and keep America neutral in the war.

In its original form, the law was broadly based, requiring that anyone promoting the interests of foreign powers in a “political or quasi-political capacity” — that is, propagandizing — disclose the relationship and report regularly on what he or she was doing, who was financing those efforts, and how the money was being spent.

Although the FARA law itself didn’t actually prohibit propagandizing, it sought to limit the influence of foreign agents by exposing their activities to sunlight. It also served as another tool that authorities could use in prosecuting any criminal espionage cases that might arise.

Failure to file the required reports was a federal offense. Since foreign agents were required to report their contacts with members of Congress and government officials, the law also marked the first attempt at major lobbying reform at the federal level.

Over the years, however, FARA has been enforced sparingly—and selectively. During World War II, it was used to prosecute some 23 criminal cases, and authorities employed it in later years against a few prominent activists ranging from South Korean lobbyist Tongsun Park (in 1977) to five Cuban intelligence officers charged with spying on U.S. military installations in the South (in 1998). Several of the most prominent cases were settled through plea-bargaining or were dismissed. Anna Chapman, the Russian spy who recently tweeted a marriage proposal to NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden, pleaded guilty to violating FARA.

In 1966, the law was amended to focus more narrowly on lobbyists, law firms, public relations firms, and associations working to influence federal decision-making on issues where foreign governments or groups associated with them are seeking economic or political advantages. Congress also authorized the Justice Department to seek civil injunctions where necessary to ensure that foreign agents comply with reporting requirements.

Today, the law requires U.S.-based individuals or groups representing foreign governments, government-sanctioned organizations, and political parties to provide detailed reports at least twice a year on their lobbying activities and contacts that involve U.S. lawmakers, government officials, business groups, and journalists.

The Justice Department has had a mixed record in administering the FARA reporting requirements, with inadequate resources and outmoded equipment. In 2004, its Foreign Agents Registration Unit conceded that its FARA database and filing apparatus had had broken down.

Three years later, the department launched an online database that can be used to search filings and current reports, but the actual reporting by foreign agents has been inconsistent, often incomplete, and shoddy. Congress’s watchdog agency, the GAO, has warned repeatedly that the FARA unit hasn’t had the money and resources to maintain the system properly.