The case of the missing executive orders: (A lack of) transparency in Georgia’s government

Last week we discussed the accessibility of gubernatorial executive orders in all fifty states. There’s still a ways to go, but at a minimum, almost all of the states put their executive orders online for the public to view. All except for one: Georgia.

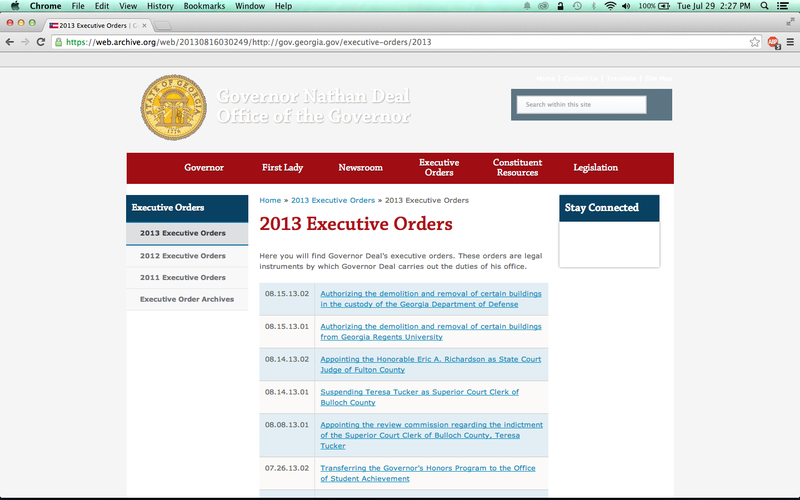

Last November, Georgians visiting the governor’s webpage would have seen something like this:

Today? Those same links are all blank pages. Some time over the Thanksgiving holiday last year, the governor’s office quietly took down nearly three years’ worth of Gov. Nathan Deal’s executive orders, and they haven’t publicly posted a single order since. The office provided no explanation for the removal of the existing orders, and there’s no information on the governor’s website about how to find executive orders. (The link to an archive of executive orders from the previous administration of Gov. Sonny Perdue, however, is still fully functional.) The only public notification of the issuing of executive orders comes from press releases from the governor’s office, but the office doesn’t announce every executive order, and press releases are by no means a substitute for the documents themselves.

Deal is no slouch when it comes to executive orders — he’s issued more than 200 of them since the beginning of the calendar year and issued around 600 in 2013. Georgia ranks second in the country in number of executive orders issued in the last five years, a product of the structure of Georgia’s constitution, which requires many executive branch responsibilities to be fulfilled by executive order. Many orders are appointments to state agencies, commissions and boards — including the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia, the Georgia Port Authority and Board of Natural Resources. Others concern the transfer of funds from emergency accounts and responses to natural disasters. None of them are on the governor’s website. Without better public information about the nature of these discretionary appointments and fund transfers, it is very difficult to know who the governor is appointing or what he is choosing to do with state money.

When we contacted the governor’s office to ask how the orders could be accessed by the public, we were told that interested parties could come to the governor’s office and view them there. People who can’t make the trek to Atlanta can, with some effort, obtain them by emailing staff in the office of the governor’s general counsel. Of course, you can’t ask for what you don’t know exists, so you’ll want to ask for a list of executive order titles first. Relying on these methods to keep up with goings-on in the governor’s offices, however, is both time-intensive and potentially costly.

The somewhat good news is that despite the governor’s apparent intentions, these documents are in fact not entirely inaccessible to the public online. Georgia Government Publications (GGP), a project of the Digital Library of Georgia (part of the University System of Georgia), has been uploading these documents as part of their digitization project. While the lag time is in the order of weeks and the document titles aren’t available, at least the full text of the documents is searchable.

Strangely enough, an initial comparison of the list provided to Sunlight by the Georgia governor’s office and the archive maintained by Georgia Government Publications (GGP) reveals several executive orders in the archives that aren’t included on the governor’s office’s list. The orders appoint members of the Deal administration to a review commission examining the indictment of Harris County Commissioner Charles Wyatt for bribery and violations of oath, and appoint representatives to two interstate commissions — a state representative to the Goldwater Institute-engineered Compact for a Balanced Budget and two to the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws. None of these actions were announced by his press office, and it was only by combing the archives that we could find this information at all. No one can dispute that the GGP documents are a useful stop-gap resource, but this isn’t what transparency in governance looks like.

In an age of web archiving and search engine caching, very little of the information that we publish online can be hidden permanently and forever. As such, executive orders in Georgia are available to the public in a narrow sense — accessible to those who have the resources to go to the governor’s office during regular business hours or the foreknowledge to search in the University of Georgia’s databases. But that’s not the point.

Gone are the days when getting out the news required printed notices and town criers. In the eight years prior to Deal’s administration, Georgia had the means and the sense to publish its executive orders online — to have removed them from the governor’s website is an inexplicable and inexcusable step backward for transparency in Georgia’s government. Open government isn’t just free data and documents for those who have the time and expertise to find and make sense of them. It’s a commitment to make as much of the workings of government, from the prosaic to the powerful, fully and freely available to the people it serves.

Nevertheless, now that we have access to this data, here are some questions that have been on our mind lately:

- We’ve already found three executive orders that aren’t on the official list and weren’t publicized by the governor’s press office. What else has been effectively obscured from public view and appears only in the Georgia archives?

- The Governor’s Emergency Fund is a rainy-day fund with a budget of more than $20 million. The Governor authorizes transfers from this fund to support everything from conflict-free public defenders to interest payments on debts owed to the Department of Labor. Where and how else are these funds being spent?

- News organizations in other states have taken a fine-toothed comb to political contributions made by gubernatorial political appointments. A cursory analysis of campaign finance records for appointees to the Georgia Ports Authority reveals that 12 of the 13 board members and their families have donated over $300,000 dollars to Deal’s election and re-election campaigns. How common are donations from political appointees in Georgia, whether before or after their appointments?