OpenGov Voices: Tools and NGO collaboration push Georgia to redefine “FOI as usual”

Technology, advocacy and policy share a common limitation: None of them alone can make social change happen. In the quest for more open government, advocates must seek change in all three fields at once. While digital tools are never a complete solution, conceived and deployed deliberately, tech can change both the pace of public reform and the balance of power between officials who can withhold information and citizens and NGOs who lack the leverage to demand it.

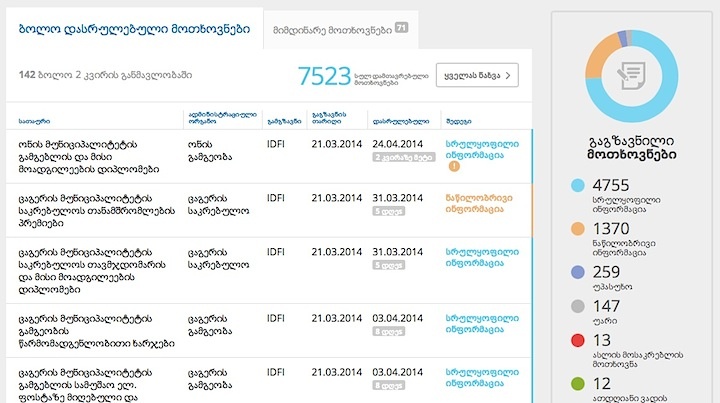

In the country of Georgia, where the climate for open government has improved since the recent political transition, four citizen groups are promoting a new level of transparency by uniting their freedom of information efforts in a single web site. OpenData.ge, launched as a four-way partnership in spring 2014 and is designed to multiply each partner’s impact and show citizens and leaders how information can combat corruption and inefficiency. The story of the site’s evolution offers valuable lessons about the role of technology in NGO strategy and the power of NGOs to influence policy using technology.

The Institute for Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI) first created the site in 2010, to publicize its government information requests and allow citizens and journalists to track the replies it got—or did not get—from each agency. At the time, “public discourse was fully monopolized by the ruling political power. Political opposition in the country was not strong,” says Vako Natsvlishvili at the Open Society Georgia Foundation (OSGF), which supported both the initial tool and the revision.

Tako Iakobidze of IDFI says that the site’s very existence also sent an important message. “Raising public awareness is essential,” says the analyst, who currently oversees the project for IDFI, “so that broader society knows about the tool of public information.”

Natsvlishvili says OpenData.ge “played one of the most important roles in ensuring accountability of public institutions.” For instance, groups including IDFI and Transparency International have used information posted in the system to drive new scrutiny and new guidelines for salary and bonuses to public officials, an issue that continues to drive policy change in Georgia.

The government has made progress toward openness and accountability in recent years and this year embarked on its second annual Open Government Partnership action plan. But since the 2008 conflict with Russia, Georgia’s civil society groups have remained ahead of its leaders in promoting democratic change.

To widen the impact of individual FOI requests and to strengthen the community of information activists, three organizations joined with IDFI in winter 2012 in a plan to publish all their requests and the resulting government replies in a single location on OpenData.ge. Along with IDFI, the Georgian Young Lawyers Association (GYLA), Green Alternative (GA) and Transparency International Georgia make up the coalition for the new OpenData.ge.

Green Alternative is a longtime environmental campaigner and advocate for citizen access to the policy process. Irakli Macharashvili, who leads GA’s biodiversity program, says he and his colleagues proposed sharing documents with other groups in order to make the most of their accumulated FOI requests. “We thought the information we have could have been used by others for their causes without wasting time and effort,” he says.

GYLA attorney Sulkhan Saladze says the site assembles a picture of not only the compliance but the “behavior” of the different offices, “by centralizing both the requests for information and the replies of each agency. It also can be an ideal tool for reporters to use directly, he says, which increases the impact of the partners and the power of journalists in an environment where independent media remains limited.

“Media does very little investigative reporting on their own” in Georgia, says independent journalist George Lomsadze, who writes regularly about the country for EurasiaNet. More often, he says, mainstream reporting merely “reflects” the statements made by politicians or NGOs. “Projects like OpenData.ge provide public information in a digestible form,” he adds, “which we, the lazy journalists, very much appreciate.”

The Open Society Georgia Foundation and the OSF Information Program funded the web project and Geneva-based technology group Huridocs was hired to create the new system, building on their expertise in digital tools to manage human rights data. Working closely with Huridocs and OSGF, the NGO partners released the newest version of OpenData.ge at the end of February 2014.

The upgrade comes at an important time for Georgia’s transparency movement. Like the website, the country’s legal regime for freedom of information has undergone an overhaul since 2012. Thanks in part to advocacy by the site partners, government agencies have new rules for FOI requests, new requirements for proactive disclosure of information and new web tools for e-government and data publishing.

However, many of these programs are delivered only in part. The federal website for data disclosure is so far a “compilation of links” to government data sources, not a source on its own, according to the Independent Review Mechanism of the OGP (IRM). The IRM also said the new government portal for citizens, my.gov.ge, is “difficult to navigate, even for technology and internet savvy users.”

And while IDFI and other groups have worked closely with Georgian officials on transparency reforms and the OGP process, Iakobidze says the government’s rate of responses to FOI requests is actually falling. She says a comparison of responses between October 2013 and March 2014 revealed a 14 percent drop in full replies, as well as a 5 percent increase in requests that were ignored altogether.

Macharashvili says government information requested by Green Alternative “is still provided with delay, or it’s incomplete, or we need administrative and court proceedings to have access.”

Tamar Kaldani, who is currently the government’s Personal Data Protection Inspector says that by compiling FOI requests and tracking responses, the NGOs have already influenced and accelerated the policy process. She says that while “major discussions on the freedom of information, accountability and transparency were initiated by civil society,” in the past, “now the government is actively involved in and often initiates these discussions.”

Kaldani has a unique vantage point on the intersection between data and accountability. She is Georgia’s first-ever official responsible for ensuring the protection of personal data by the private and public sector and also helped to conceive the ideas for OpenData.ge in her previous position as an OSGF officer.

The belief that online coordination can amplify NGO influence has been one of the project’s guiding assumptions. Though Kaldani’s comments and others show the approach is working, project managers agree that coordinating multiple groups with varied technology experience took a toll on efficiency and speed.

“Often the partners had different viewpoints on various issues, even insignificant parts of site design,” says Natsvlishvili. To help steer the group, he eventually presented the four NGOs with a project memorandum that would “regulate their relationships, rights and obligations, decision-making process.”

On the technology side, Huridocs needed to wrangle a team of experts based in multiple countries, often driving the project from their main office in Geneva. Daniel D’Esposito, who leads Huridocs, says that a classic technology consultant’s dilemma was exacerbated by the distance from the NGOs and the tech team. “We can travel and spur things and talk and make recommendations,” he says, “but we can’t tell people what to do.”

While barriers to coordination may have slowed the project, this challenge eventually led to the local groups working more closely. They now meet regularly to plan advocacy and technology strategies for OpenData.ge. With four partners working in concert, Iakobidze says “that combined effort of civil society representatives can create even more pressure.”

“They have developed a feeling of ownership of the tool,” says Vako Natsvlishvili. “Gradually, the site is turning into a platform for freedom of information.”

Jed Miller is a digital and communications strategist for the Open Society Foundations and the Transparency and Accountability Initiative (T/AI), among other groups. He is a co-organizer of the T/AI’s TABridge network, which links advocates, technologists and funders to promote more strategic uses of digital tools. He was previously Internet director at the Revenue Watch Institute and at the American Civil Liberties Union and can be found on Twitter at @jedmiller.

Interested in writing a guest blog for Sunlight? Email us at guestblog@sunlightfoundation.com