As campaign ads move online, the public gets left in the dark

There’s no doubt that television commercials are the juggernauts of campaign advertising. Campaigns and super PACs will spend hundreds of millions on commercials designed to sway voters while they watch the news, The Price is Right or even football and baseball.

However, as Americans continue to migrate over to the web as a primary source of news and entertainment, so are political campaigns. So much so, that Google, Facebook and Twitter all have pages dedicated to answering questions and soliciting political campaigns.

But as candidates and their outreach teams transition to the digital realm, it appears that disclosure and transparency are being left behind — potentially leaving the American public in the dark.

Low-cost entry, high reach, harder to track

The ads are also becoming popular because Internet companies claim you can reach many more people at a lower cost. For instance, on Facebook’s page, they point to a case study of Texas Sen. John Cornyn, R, where his campaign was able to reach a million voters for just 21 cents each. That means the campaign spent about $210,000; compare that to a television ad campaign which can cost in the millions. In another section on the political campaign page, Facebook states for $1, candidates could buy two pieces of direct mail, or they could target 200 voters on Facebook.

The bigger challenge could become whether voters can tell who is targeting them with these ads.

When it comes to television commercials, you can track who’s behind the advertisements in two ways. First, committees present them on their campaign finance reports and super PAC filings. In addition, television and radio stations are required to file information about political advertisements with the Federal Communications Commission, including who placed the ad and the amount of money. They also are required to have a disclaimer that discloses who paid for it.

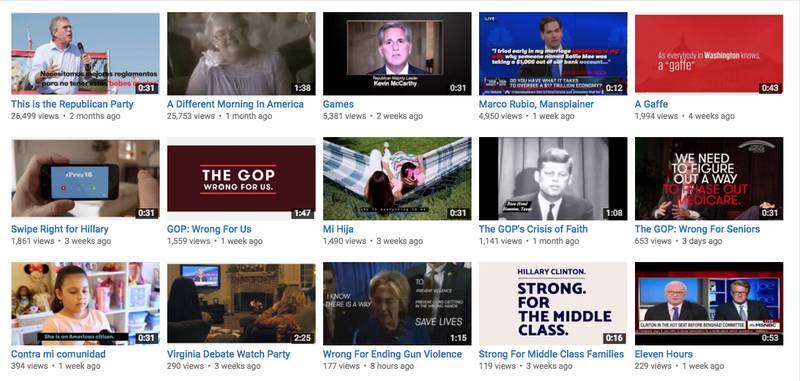

Internet campaign ads, defined by the Federal Election Commission as “communications placed for a fee on another person’s website,” can only be tracked on those campaign finance reports. Early in the cycle, we’re seeing candidates and committees sometimes break those down by line items where we can see where those ads were placed. In other cases, the candidate or super PAC just lists who they have hired to place those ads. And because the rules on online ads are so lax, a disclaimer on who’s behind the ads wouldn’t be necessary for viral videos placed on YouTube or other content distributed on services like social media.

And it becomes even murkier with “issue ads,” ads that do not explicitly advocate for or against a particular candidate. Under the current reporting regime, spending on online issue ads is only disclosed in a political committee’s disbursements, sometimes filed weeks or months after the fact and lacking information about the candidate and race targeted and type of expenditure. Other groups, like “social welfare organizations,” usually don’t have to disclose this spending to the FEC at all. And they never require a disclaimer on who or what is running them.

Spending by candidates

Spending on Internet advertisements is not isolated to the candidates struggling to raise money and stay in the race. Here are some of the highlights of what we have seen in online spending in just the third quarter of 2015:

- It’s probably not surprising given Bernie Sanders’ surge as a grassroots candidate, but his campaign has spent $2.5 million on advertising online just in the third quarter.

- Jeb Bush doled out $225,250 to web advertising placement firms Resonate, Red Digital and Locker Dome.

- Ben Carson’s Q3 report shows the campaign paid Facebook $14,582. Probably a more telling number is the amount paid to Eleventy Marketing Group, a group whose website boasts digital advertising strategies, $1,014,799. (Sure enough, this Ben Carson Facebook ad landed in my feed this week. Note the screenshot above.)

- Hillary Clinton paid $2.6 million to Bully Pulpit Interactive, the digital folks behind President Obama’s presidential run (per their website). Bully Pulpit’s success for other democratic candidates is also listed as a case study on Facebook candidate page.

- Mike Huckabee spent $85,396 in advertising with Google and Facebook.

- Lawrence Lessig, now out of the running, dropped $41,655 on Google AdWords.

- Rand Paul allocated $510,615 to Facebook and Harris Media LLC for the purpose of online ads.

Super PACs are also cashing in on Internet advertising. The super PAC supporting Jeb Bush, Right to Rise, has plunged $730,000 into web advertising, and the super PAC supporting Rand Paul, America’s Liberty, has spent about $60,000 on web ads.

On the flip side, the pro-Hillary Clinton super PAC, Priorities USA, just dropped $10,000 last week buying digital ads opposing pretty much the entire Republican field: Mike Huckabee, Donald Trump, Ben Carson, Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, Rand Paul, John Kasich, Chris Christie and Ted Cruz.

Meanwhile, The Stop Hillary PAC has spent $10,000 on digital ads opposing Clinton. Additionally, AmericaRisingPAC.org has also spent $1,000 buying digital ads opposing the Democratic frontrunner.

Some online companies proactively strive for disclosure

For a relatively low amount of money, a dark money group could place a host of Internet attack ads — and no one would ever know who’s behind them. Still, some Internet companies are making an effort for some disclosure.

For instance, in its political advertising policies, Twitter labels advertising by political entities (candidates, their committees and those making independent expenditures) with a purple badge. They disclosed who paid for the advertising campaign, and the advertiser’s account must include a link to a website with more information about the organization.

Of course, this is just regarding paid advertisements. There are myriad things that campaigns could do online that do not fall under “communications placed for a fee on another person’s website.” Uploading content to YouTube, paying people to place content on social media, creating memes to share online and other grassroots efforts do not fall under these rules.

Whether or not the FEC or another agency decides to tackle this “online blind spot” remains to be seen.