Influence Abroad: American vulture funds feed on Argentina’s debt crisis

During President Barack Obama’s visit to Argentina in March 2016, the press didn’t waste any time asking the American president and his newly elected counterpart, Mauricio Macri, about a raw point in relations between the two nations: the heated legal battle between Argentina and several American hedge funds that held out for better repayment terms after the South American country defaulted on $100 billion in debt in 2001. The default and subsequent impasse kept Argentina from selling bonds on the international market and, in turn, crippled the nation’s economy.

“How do you view the current negotiation between Argentina and the holdouts, or the way we call them here, the ‘vulture funds?’” asked Liliana Franco of Argentina’s Ambito Financiero Newspaper1, utilizing the term frequently used by the previous administration to refer to holdout investors.

Franco’s question underscored years of tense relations between Argentina and the United States, hinting at the anti-American sentiment still lingering in the country over the belief that vulture funds hijacked the country’s economy as it tried to recover from defaulting on billions of dollars in debt racked up while dictators ruled the South American country. Several funds held out on a debt settlement agreement that most investors approved and eventually took the country to court in the United States to force full repayment. In some countries, it is difficult for ordinary people to link the actions of hedge funds to their everyday lives, but in the case of Argentina, the decision by vulture funds to hold out for a better repayment deal crippled Argentina’s economy, affecting nearly every Argentine’s life in some way. The country’s president seized on that populist anger over decades of financial struggles and used the term “buitres” — Spanish for vultures — to fan the flames of resentment toward the United States.

After first declining to speak specifically about the legal case about repayment, which was still playing out in the American court system, President Obama said to the press:

To some degree, this is viewed as high finance, and so ordinary people say why does this matter. But if you’re talking about foreign investment, if you’re talking about trade, if you’re talking about all the things that ultimately matter to ordinary people because they produce jobs and they produce economic development and provide more revenue in order to reinvest in education, or science and technology, that requires the kind of financial stability that is so important.

Just a couple weeks prior to Obama’s visit to Argentina, new president Mauricio Macri made a deal with these funds — seeking to fulfill a campaign promise to move past decades of instability and help the nation return to the international banking system. Voters in Argentina had narrowly selected Macri as their new president, ending more than a decade of rule by the Kirchners, who had passionately fought the investors that held out on the country’s initial offering to settle debt for 30 percent of the original borrowed value. The final price: Argentina would pay 75 percent of what was owed and some legal fees.2

Macri sold the move to the Argentine people as a way to move his country forward. Argentina would finally be able to sell bonds on international markets. Even though it appears this lengthy dispute is coming to a close, it still has left a lasting legacy on the global monetary system as the international community looks for a way to handle the bankruptcy of sovereign states and the impact of what some refer to as “vulture investors.” The practice has been going on for decades, but this time, a battle between the funds and a country with a large voice on the international stage has helped shed light on a practice that the United Nations has described as a violation of human rights.3

What are vulture funds?

To understand what a “vulture fund” or “vulture investor” is, you have to understand the process of what happens when a nation defaults on its debt and has to negotiate a plan for repayment.

When a country sells bonds internationally, country leaders typically sign the loan papers in New York, London, Paris or Frankfurt, cities where there is established law governing financial agreements.

If the country defaults, it typically works through some sort of debt restructuring where government financial leaders meet with creditors to figure out a way to repay the debt. During that restructuring, the entities holding the debt have to agree to the amount of repayment which is usually much, much less than the original borrowed amount. When the majority of creditors reaches an agreement with the defaulted country, those who do not agree to are called “holdouts.”

In some cases, once a country defaults, new investors will sweep in and offer to buy the debt from the original investors for pennies on the dollar. Those new creditors then hold out on the debt restructuring agreement and file litigation in court where the papers were signed seeking repayment for the full amount. The new creditors stand to make substantial profits by fighting for the full amount instead of settling for the lesser sum.

This activity is primarily conducted by hedge funds. A hedge fund is a private, pooled investment group run by an individual or small group of individuals who manage the investments. Unlike other investment options, these types of groups have little to no regulation by the Securities and Exchange Commission. It’s important to point out not all hedge funds are engaged in this practice and some very much deplore the nickname “vulture funds.”

That’s because the practice is highly controversial among those who believe holding out is just a good investment strategy and those who compare the practice to vultures feasting on carrion. The term is credited to a 1996 New York court decision involving the country of Panama and Elliott Associates.4 However, the term really caught on when it was used prolifically by the previous Argentinian administration lead by Cristina Kirchner to draw attention to the practice.

Typically, when a country defaults on its debt, the parameters of how the debt is repaid need to be renegotiated. Since the restructuring includes revising things like how much is owed, the repayment schedule and the interest rate, the new terms of the agreement need to have unanimous support from the investors. To prevent a few holdouts from tanking an entire repayment agreement, the international community has urged countries to have a clause inserted into the contract called a collective action clause. This clause allows less than unanimity to change the terms of the agreement to prevent a few holdout investors from tanking the whole deal.

Argentina did not have a collective action clause included. So in 2001, when Argentina defaulted on $100 billion in debt, these so-called vulture funds saw this as an opportunity to make money. They swooped in and bought up debt from the previous investors and then refused to agree to the new terms offered by Argentina.

The previous effect of vulture funds in developing nations

Before the vulture funds went after Argentina for repayment, the practice had received little attention until that point, as it had primarily been used in developing countries like Zambia and the Congo.5 Many of those countries were governed by dictators and drew less attention on the global stage.

Though, as we mentioned, the term “vulture fund” is credited to have come from a 1996 New York court decision involving the country of Panama and Elliott Associates6, former President Cristina Kirchner used it to her political benefit, drawing attention to the practice both domestically and internationally.

Just before the worldwide recession of the 1980s, many Central American countries had borrowed large sums of money to improve their infrastructure. When the recession hit, many of the countries in Latin America found the amount of money far exceeded their ability to pay and defaulted on their debts.

In 1989, Panama restructured debt it had incurred from 1978 and 1982 through a new program offered by the U.S. Treasury. By late 1995, two of the banks that owned the debt from 1982, Citibank and Swiss Bank Corporation, sold that debt to Elliott Associates — a hedge fund led by prominent Republican megadonor Paul Singer. Initially, Panama kept up on debt payments by paying the interest on the loans, but eventually, Panama ceased payments altogether.

Elliott filed suit in New York court, where the initial loan papers had been signed, demanding full repayment of the original face value of the loan in spite of the fact that many creditors had already agreed to accept repayment values far less than expected.

Up until this point, no entity had gone after a sovereign nation for debt in U.S. court. The move was highly controversial because it was taking a sovereign nation to another country’s court to face collection.

The court ruled in favor of Elliott.

This decision set a precedent and Elliott would do the same thing in several more international debt suits, including suits in Peru7, Congo8, Vietnam9 and most recently in Argentina.

Argentina’s turbulent debt history

In the case of Argentina, problems started decades before under what a United Nations investigator called “questionable circumstances,” referring to the brutal military dictatorship in charge which started racking up millions of dollars in loans.10 This time period of terrorism between 1974 to 1983, following Juan Peron’s death, is often referred to as “the Dirty War”; it was a time when the military dictatorship was hunting down, kidnapping and killing opponents and dissidents believed to be aligned with socialism.11 Thousands of Argentines “disappeared” and some were put on “death flights” — where they were put on a flight, then dropped from an airplane into the Atlantic Ocean to their death.12

Despite these known human-rights abuses, some international banks continued to lend money to the Argentine government. Some believe that propped up the military dictatorship, enabling the regime to stay in power by giving them access to money to fight a war against its own people that lead to more than 30,000 Argentinians “disappearing.” Many Argentinians still blame the United States for not speaking out against the human rights atrocities of this regime. Argentine activists have demanded answers to the United States involvement in this period of Argentine history.

Argentina has defaulted on its sovereign debt eight times in its country’s history.13 In the 1990s, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) started advising the country on economic policies. To fight inflation, the country pegged its peso to the American dollar (meaning it has fixed its exchange rate to the American dollar in an effort to ensure stability).

The IMF received a lot of criticism for how it handled the situation in Argentina, including from the IMF itself. In 2004, an internal audit released by the IMF suggested that ignoring Argentina’s growing indebtedness while continuing to lend the nation money “significantly contributed to one of the most devastating financial crisis in history.”14

The global economic downturn of the late 1990s ended up having a devastating effect on the Argentina, causing it to enter a depression in 1998 that shrank its economy by approximately 28 percent, according to one study done by the Joint Economic Committee of the United States Congress.15 The committee reported that the economy was on the verge of recovery, but a package of three tax increases prevented growth.

In 2001, after a series of resignations by key government leaders, Argentina defaulted on its loans.16 Coming in December 2001, just months after the attacks of Sept. 11, it received little fanfare as the world’s attention was decidedly elsewhere. Around the time Argentina defaulted, NML, a subsidiary of the U.S. hedge fund Elliott Management, purchased the defaulted Argentine debt (also known as “bad” debt) for pennies on the dollar. Argentina tried to make an agreement with investors, and most of them agreed to take less than the amount owed. However, NML and a few other investors held out on that agreement and NML filed for repayment in New York court, where banks had issued the loans to Argentina.

Then-president Cristina Kirchner refused to bow to the vulture funds, saying their demands amounted to extortion. She agreed to pay back those funds which had agreed to the new terms, but refused to pay the funds who held out on the deal. The holdout funds filed suit in court in New York to stop that repayment from happening. A judge not only ruled in the funds favor, but also issued an injunction to keep financial institutions from taking action which would violate that ruling.17

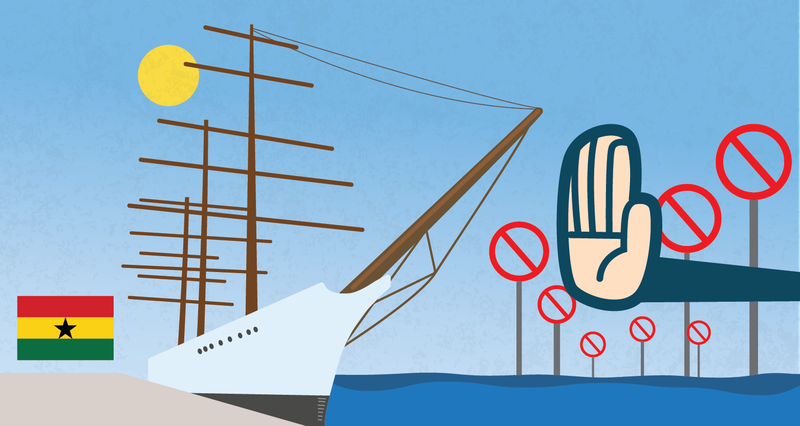

Then, the vulture funds took another radical step to force Argentine leaders to the negotiation table. On Oct. 1, 2012, the grand Argentine naval vessel ARA Libertad — carrying 325 crew members — docked in Port of Tema, Ghana. The vessel had spent several months on a training mission, and along with Argentine military members, it was also carrying military members from other countries. The ARA Libertad should have left port on Oct. 4, 2012; instead, the Ghanaian military blocked it from setting sail.

German creditors had tried to seize the training vessel when it ported in Germany in 2002, but they were unsuccessful. Now, Cayman Islands-based Elliott subsidiary NML successfully filed for an injunction in a Ghanaian court to impound the ship until the Argentine government paid back $20 million in debt it owed the hedge fund.

The International Tribunal for Law of the Sea18, the U.N. court that oversees maritime disputes, would eventually rule the ship returned to Argentina, but not before months of legal arguments forced the Argentine government to pay to repatriate 281 members of the naval crew.

The incident would also pour gas on an already volatile situation. Attorneys for the Argentine government would advise then-president Kirchner to ground the presidential plane, Tango 01, due to concerns that the plane could suffer the same fate as the ARA Libertad.19

According to The Wall Street Journal, Argentina would charter a plane for Kirchner’s trip to other nations to promote trade with her country at a cost of $880,000 for a week of travel or “20 percent more than it would have cost to travel in Tango 01.”

Kirchner also used the situation to fuel political propaganda about the undue influence of American hedge funds on the Argentine economy, which caused anti-American sentiment to grow within the country. Though there were other hedge funds among the 8 percent of investors who also held out of the deal — including New York’s Aurelius, Boston’s Bracebridge Capital as well as a few wealthy Argentinians — Elliott Management founder Paul Singer became the face of the holdouts to the Argentine people. Singer’s name is well known in the world of American politics, and he’s supported many Republican candidates, including New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, former presidential candidate Mitt Romney and most recently Sen. Marco Rubio’s failed campaign for president.20 However, Singer was now the symbol of American greed and was assigned blame for the collapse of Argentina’s economy.

Instability in the current financial system

Experts worry that this current system of dealing with the default of sovereign nations (or lack thereof) creates instability in global markets, as seen most recently with Greece and Puerto Rico. The IMF is supposed to be the stop gap to prevent this sort of instability; it was established following World War II with the purpose of ensuring the stability of global markets and is supposed to be mentoring troubled countries about how best to deal with their debt crisis.

The IMF itself was under scrutiny since it had been involved in the country’s financing since 1991, and its advice should have prevented default. However, the biggest worry of the IMF is that funds that the IMF uses to help restructure debt will actually not be spent on the debt, but paying off vulture funds who have held out on the deal in order to get the full price. This is what happened most recently in Greece.21 (The Jubilee Debt Campaign UK estimates 90 percent of the $252 billion euros spent to bail out Greece actually went to lenders and not the Greek people.22)

At one point, the IMF openly considered filing an amicus brief in Argentina’s case, urging the court to take action to prevent this type of situation from taking place.23 But for unknown reasons, the IMF never actually went through with filing that brief.

An independent investigator reporting to the U.N. in April 2010 testified that it’s hard to tell exactly how many lawsuits have been filed by vulture funds, but estimated that number to be at least 50.24 Meanwhile, an IMF working paper estimated 109 lawsuits were filed between 1980 and 2010.25

There have been efforts to get some sort of multilateral “bankruptcy court” or “debt restructuring law” established to have jurisdiction over sovereign debt. In the absence of these laws, vulture funds typically use U.S. local law and court decisions to enforce payment. Some hedge funds do worry that using U.S. law in this way could drive business away from the U.S.; countries would try to avoid becoming victim to the same law that took down Argentina’s economy by choosing to sign loan papers in places with laws more favorable to sovereign nations in case of a default.

Cristina Kirchner argued the practices of holdouts that devastated her nation’s economy and the economies of several others amounted to human rights abuse. She took her case to the United Nations, which ultimately passed a resolution proclaiming the practices as such. The U.N. pushed to start a multilateral debt restructuring process by passing a resolution urging countries to pass policies to protect countries from holdouts.26 But the resolution was nonbinding27, and after nearly two years, the process to set up an international structure to handle these sort of bankruptcies has gone virtually nowhere. In one crucial vote to establish a framework, the U.S., U.K., Germany and Japan all voted against the measure. Forty-one other countries, including the European Union as a whole, abstained.28 A United States delegate told reporters the language in that resolution was “problematic.”

Kirchner would continue to draft conspiracy theories that, backed by the vultures, the United States was crafting a conspiracy to possibly assassinate her.

“If something should happen to me, don’t look to the Middle East, look to the North,” Kirchner said in a televised address.29 However, it would not be the United States, but ultimately a vote of an exhausted Argentine people, which would end the Kirchner influence on Argentine politics — voters chose Macri over Kirchner’s preferred successor, Daniel Scioli, in the most recent elections.30

How vulture funds influence policy

While the effort to create an international framework hasn’t progressed in the last couple of years, some experts believe that action could be taken at the state level to prevent situations like what happened to Argentina from happening again, preventing countries from taking their business (i.e. signing their loan papers) in places where the courts might be more favorable to sovereign nations. Some hedge funds have expressed worries that what vulture funds make in money now could cost the overall American economy later.

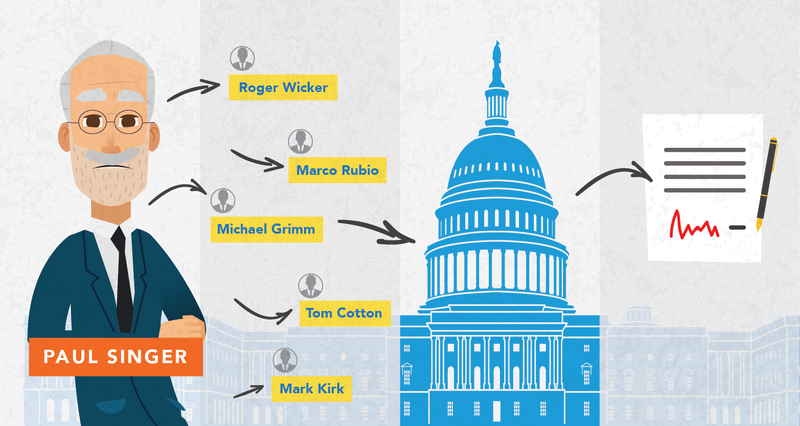

Meanwhile, lobbying around the issue of Argentina shows distinctly how influence within the U.S. as well as campaign contributions can influence global affairs. Singer’s group Elliott Management has lobbied at the local and federal level to create a more favorable environment for court cases like the one it filed. In June 2012, the hedge fund supported legislation in the New York state Senate and Assembly which would “allow the fund to pursue post-court judgment.” Elliott’s group is reportedly the primary funder a lobbying group called “American Task Force Argentina” representing the interests of holdout investors.

On a website dedicated to the conflict, the Embassy of Argentina lists $6.5 million in lobbying expenditures31 made by American groups for legislation to make Argentina pay back $3 billion owed to U.S. holders of Argentine debt. In addition, the Argentine government made a list of politicians to whom Singer and Elliott Management had given money to support. Those include: Rep. Scott Garrett, R-N.J., who sponsored the Judgement Evading Foreign States Act (JEFSA) and held congressional hearings on the matter; former Rep. Michael Grimm, R-N.Y., who co-sponsored the bill; as well as Sens. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., Tom Cotton, R-Ark., Mark Kirk, R-Ill., and Roger Wicker, R-Miss. — all of whom, according to Argentina, also “signed letter against Argentina.” (Senators Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) and Robert Menendez (D-NJ) also signed that letter.)

Singer also backed Rubio’s run for president. According to the International Business Times, Rubio sponsored an amendment to “direct American officials at international financial institutions like the World Bank to deny development loans to Argentina until that country’s government ‘makes substantial progress’ in repaying creditors like Elliott Management.”32

In 2007, Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif., proposed the “Stop VULTURE Funds Act,” but the bill never made it off the ground, according to the Center for Economic Policy and Research. It was opposed by Singer’s American Task Force Argentina, which reportedly spent more than $3 million to fight that legislation. ATFA also supported legislation sponsored by former Rep. Connie Mack, R-Fla., that would have compelled Argentina to pay the $2 billion it owed Singer’s NML. (Elliott employees were listed as the biggest contributors to Mack’s failed Senate run against Bill Nelson.)

A brighter future for Argentina and the world?

Just weeks after Mauricio Macri’s election, Moody’s changed Argentina’s outlook from “stable” to “positive,” citing Macri’s campaign promises for a more market-friendly approach compared to the previous 12 years of Peronist rule.33 The rating action also noted:

A prompt resolution of the holdout saga is a key Macri pledge in this regard, and is required for the government to borrow abroad, which it will probably need to do in order to meet upcoming debt service obligations. Official reserves have fallen to below $22 billion, raising uncertainty about the government’s ability to meet 2016 debt service obligations and adding pressure for a swift resolution with holdout creditors.

In February 2016, Macri fulfilled that promise, perhaps gaining political capital from a people exhausted by the toll the battle has taken on Argentina’s economy. However, the true winners are still the hedge funds who bought up the bad debt and now will make millions. Martin Guzman and Joseph E. Stiglitz wrote in The New York Times, “NML Capital will receive about half of the total agreement — $2.28 billion for its investment of about $177 million, a total return of 1,180 percent.”34

(Note: Elliott Management disputes the figure of its initial investments. Estimates have ranged between $49 million and $617 million.)

CNN estimated another firm, Bracebridge Capital from Boston, would make an 800 percent return on the investment it originally made by purchasing Argentina’s defaulted debt.35

In an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal, Paul Singer called this a victory for the rule of law:

Throughout this saga, certain commentators and policy makers have argued that the enforcement actions imposed by U.S. courts on Argentina have set a negative precedent for future sovereign-debt restructurings. They claim that bondholders now have little incentive to negotiate a resolution.

This line of thinking is wrong—and it risks crippling markets for sovereign debt.36

Singer continued to say if courts couldn’t enforce payment of the debt, then worries over the bonds of sovereign countries with poor credit histories might tank bonds at any sign of instability. He questions who would take risks on bonds that may not be repaid. “Such a world would be far more chaotic than the imperfect but workable set of legal fallbacks that investors rely on today,” Singer wrote. (The op-ed does not examine whether, from a business aspect, it was a tremendously risky move to buy troubled debt obtained originally by a military dictatorship guilty of vast human rights abuses, though NML disputes any connections to debt taken on during that regime. The fund believes all of its bonds were issued during the 1990s after the regime’s fall. It also does not speak of the laws Singer himself has tried to influence.)

Still, the move frees up Argentina to issue bonds internationally for the first time in 15 years. The Argentine government promptly scheduled a roadshow in the United States and the United Kingdom to showcase the country as a place to invest. Though the country hopes it has turned the page, it’s unlikely that anyone will soon forget what has happened. Questions surrounding Argentina’s debt history and eight defaults will likely be raised with the policymakers and bankers on the trip37, and international leaders will likely continue to debate the impact of vulture funds on sovereign nations.

But the wounds between Argentina and the U.S. may still be slow to heal. During Obama’s visit, protesters gathered outside a McDonald’s objecting to U.S. influence in their country, with some protesters specifically citing the “Dirty War.”38 At the same time, Obama announced that he would open up and release intelligence and military documents about the U.S. involvement in the so-called “Dirty War” in an effort to shed sunlight on the still shadowy relationship between the two nations.

Macri agreed this release of documents related to U.S. involvement in that military dictatorship would help the people of Argentina know the truth about this time period. One of the great things about America, Obama reportedly told the crowd, is that “we engage in a lot of self-criticism.”

While that certainly is true, American wealth and political power has sometimes played an oversized role in influencing the economics of sovereign nations. By destabilizing entire nations, it is not the politicians in power — the individuals who made the deals — who suffer the consequences. It is the average citizens who don’t have a job, or can’t afford food or a home due to the financial turmoil. In the case of dictatorships, the people also have no way to influence their government to make better decisions. So, while the United States continues to engage in “self-criticism,” the world waits to see if any of that will be directed at defining a better system to handle defaults by sovereign nations.

Footnotes

- 1 Remarks by President Obama and President Macri of Argentina in Joint Press Conference. (2016). Retrieved April 01, 2016, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/03/23/remarks-president-obama-and-president-macri-argentina-joint-press (Return to text)

- 2 Fisher, D. (2016, February 29). Paul Singer Wins Long Battle With Argentina; Have Emerging Market Bonds Hit Bottom? Forbes. Retrieved April 1, 2016, from http://www.forbes.com/sites/danielfisher/2016/02/29/paul-singer-wins-long-battle-with-argentina-have-emerging-market-bonds-hit-bottom/#667db254f04a (Return to text)

- 3 Human Rights Council. (2014, October 3). United Nations Official Document. Retrieved April 01, 2016, from http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/HRC/RES/27/30 (Return to text)

- 4 Elliott Associates, LP v. Republic of Panama, 975 F. Supp. 332 (S.D.N.Y. 1997) (United States District Court, S.D. New York. September 10, 1997). http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/975/332/1458911/ (Return to text)

- 5 Huang, D. (2014, June 25). What Happens When the Vulture Funds Start Circling. Retrieved April 06, 2016, from http://blogs.wsj.com/moneybeat/2014/06/25/what-happens-when-the-the-vulture-funds-start-circling/ (Return to text)

- 6 Elliott Associates, LP v. Republic of Panama, 975 F. Supp. 332 (S.D.N.Y. 1997) (United States District Court, S.D. New York. September 10, 1997). http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/975/332/1458911/ (Return to text)

- 7 ELLIOTT ASSOCIATES, L.P., Plaintiff-Appellant, v. BANCO DE LA NACION and the Republic of Peru, Defendants-Appellees (United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit October 20, 1999). http://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-2nd-circuit/1201641.html (Return to text)

- 8 Polgreen, L. (2010, December 7). Unlikely Ally Against Congo Republic Graft. New York Times. Retrieved April 1, 2016, from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/10/world/africa/10congo.html?ref=finances&_r=0 (Return to text)

- 9 Steger, I. (2011, December 12). Hedge Fund Elliott Associates Takes Vietnam to Court. Retrieved April 01, 2016, from http://blogs.wsj.com/deals/2011/12/12/hedge-fund-elliott-associates-takes-vietnam-to-court/ (Return to text)

- 10 UN Human Rights. (2014, November 27). Human rights impact must be addressed in vulture fund litigation – UN experts. Retrieved April 01, 2016, from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=15354 (Return to text)

- 11 Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. “Dirty War”, accessed April 22, 2016, http://www.britannica.com/event/Dirty-War (Return to text)

- 12 Mason, Jeff. “Obama Honors Argentina’s ‘Dirty War’ Victims; Faults U.S. on Human Rights.” Reuters. March 25, 2016. Accessed April 22, 2016. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-argentina-idUSKCN0WQ0I9 (Return to text)

- 13 “Eighth Time Unlucky.” The Economist. August 02, 2014. Accessed April 18, 2016. http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21610263-cristina-fern-ndez-argues-her-countrys-latest-default-different-she-missing (Return to text)

- 14 Paul, B. (2004, July 30). IMF Says Its Policies Crippled Argentina. Retrieved April 06, 2016, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A25824-2004Jul29.html (Return to text)

- 15 Schuler, K. (2003, June). ARGENTINA’S ECONOMIC CRISIS: CAUSES AND CURES (United States, Joint Economic Commission, Congress). Retrieved April 1, 2016, from http://www.jec.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/5fbf2f91-6cdf-4e70-8ff2-620ba901fc4c/argentina-s-economic-crisis—06-13-03.pdf (Return to text)

- 16 Hornbeck, J. (2010, July 2). Argentina’s Defaulted Sovereign Debt: Dealing with the “Holdouts” (United States, Congressional Research Service). Retrieved April 1, 2016, from http://fpc.state.gov/documents/organization/145568.pdf (Return to text)

- 17 Blustein, Paul. “Why Argentina’s Debt Deal Spells Bad News.” Fortune Why Argentinas Debt Deal Spells Bad News Comments. March 17, 2016. Accessed April 18, 2016. http://fortune.com/2016/03/17/argentina-debt-settlement-2/ (Return to text)

- 18 Argentina v. Ghana (International Tribunal for Law at the Sea December 15, 2012). https://www.itlos.org/cases/list-of-cases/case-no-20/#c1081 (Return to text)

- 19 Romig, S. (2013, January 7). Argentina Grounds President’s Plane. Retrieved April 01, 2016, from http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323482504578228104091786888 (Return to text)

- 20 Haberman, Maggie, and Nicholas Confessore. “Paul Singer, Influential Billionaire, Throws Support to Marco Rubio for President.” The New York Times. October 30, 2015. Accessed April 13, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/31/us/politics/paul-singer-influential-billionaire-throws-support-to-marco-rubio-for-president.html?_r=0 (Return to text)

- 21 Stiglitz, J. (2015, June 16). Sovereign debt needs international supervision. Retrieved April 04, 2016, from http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/jun/16/sovereign-debt-needs-international-supervision (Return to text)

- 22 “At Least 90% of the Greek Bailout Has Paid off Reckless Lenders – Jubilee Debt Campaign UK.” Jubilee Debt Campaign UK. January 18, 2015. Accessed April 22, 2016. http://jubileedebt.org.uk/press-release/least-90-greek-bailout-paid-reckless-lenders (Return to text)

- 23 Bases, Daniel. “IMF to File Brief with U.S. Supreme Court in Argentina Case.” Reuters. July 17, 2013. Accessed April 13, 2016. http://www.reuters.com/article/imf-argentina-bondholders-idUSL1N0FN2JB20130718 (Return to text)

- 24 “United Nations Official Document.” UN News Center. April 29, 2010. Accessed April 13, 2016. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/HRC/14/21 (Return to text)

- 25 International Monetary Fund. Sovereign Debt Restructurings 1950–2010: Literature Survey, Data, and Stylized Facts. By Udairbir S. Das, Michael G. Papaioannou, and Cristoph Trebesch. August 2012. Accessed April 13, 2016. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12203.pdf (Return to text)

- 26 Bohoslavsky, J. P. (2015, January 26). Towards a multilateral legal framework for debt restructuring: Six human rights benchmarks States should consider. Retrieved April 6, 2016, from http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Development/IEDebt/DebtRestructuring.pdf (Return to text)

- 27 Deutsche Welle. (2015, November 9). UN backs Argentina in debt dispute with ‘vulture’ funds | Business | DW.COM | 11.09.2015. Retrieved April 06, 2016, from http://www.dw.com/en/un-backs-argentina-in-debt-dispute-with-vulture-funds/a-18708466 (Return to text)

- 28 Inman, Phillip. “Debt Campaigners Hail UN Vote as Breakthrough.” The Guardian. September 11, 2015. Accessed April 22, 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/sep/11/debt-campaigners-hail-un-vote-as-breakthrough (Return to text)

- 29 Goñi, Uki. “Argentina President Claims US Plotting to Oust Her.” The Guardian. October 01, 2014. Accessed April 22, 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/01/argentina-president-claims-us-plot (Return to text)

- 30 “Argentina’s Macri Ousts Leftist Peronists from Power.” Reuters. 2015. Accessed April 22, 2016. http://www.cnbc.com/2015/11/22/argentinas-elections-produce-win-for-macri-exit-polls.html (Return to text)

- 31 “Disfruta De Lobbying Against Argentina and Contributions to Political Campaigns by Elliot Management and Paul Singer.” Argentina Embassy in Washington. Accessed April 18, 2016. http://www.embassyofargentina.us/en/embassy/argentinas-sovereign-debt-restructuring/lobbying-against-argentina-and-contributions-to-political-campaigns-by-elliot-management-and-paul-singer.html (Return to text)

- 32 Sirota, David, and Andrew Perez. “GOP 2016: Marco Rubio Helps Big Campaign Donor, Pressures Argentina For Full Debt Repayment.” International Business Times. November 06, 2015. Accessed April 18, 2016. http://www.ibtimes.com/political-capital/gop-2016-marco-rubio-helps-big-campaign-donor-pressures-argentina-full-debt (Return to text)

- 33 Global Credit Research. (2015, November 24). Moody’s changes Argentina’s outlook to positive from stable; Caa1/(P)Caa2 ratings affirmed. Retrieved April 01, 2016, from https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-changes-Argentinas-outlook-to-positive-from-stable-Caa1PCaa2-ratings–PR_339171 (Return to text)

- 34 Guzman, M. and Stiglitz, J. (2016, April 1). How Hedge Funds Held Argentina for Ransom. Retrieved May 2, 2016, from http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/01/opinion/how-hedge-funds-held-argentina-for-ransom.html (Return to text)

- 35 Gillespie, Patrick. “This Fund Made an 800% Return on Argentina Debt.” CNNMoney. March 2, 2016. Accessed April 13, 2016. http://money.cnn.com/2016/03/02/news/economy/hedge-funds-argentina-debt/ (Return to text)

- 36 Singer, Paul. “The Lessons of Our Bond War.” WSJ. April 24, 2016. Accessed April 25, 2016. http://www.wsj.com/articles/the-lessons-of-our-bond-war-1461531781?cb=logged0.03575673419982195 (Return to text)

- 37 Singer, Paul. Platt, Eric, and Benedict Mander. “Argentina Launches Bond Comeback Roadshow – FT.com.” Financial Times. April 10, 2016. Accessed April 13, 2016. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/fd2f3972-fdc9-11e5-b3f6-11d5706b613b.html#axzz45jLseox6 (Return to text)

- 38 Lederman, Josh, and Peter Prengaman. “On a Fence-mending Mission, President Barack Obama Holds up Argentina as an Emerging World Leader Worthy of U.S. Support, as He and Argentine President Mauricio Macri Break with Years of Recent Tensions between Their Countries.” Associated Press. March 23, 2016. Accessed April 18, 2016. http://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2016-03-23/in-buenos-aires-obama-aims-to-boost-argentinas-new-leader (Return to text)