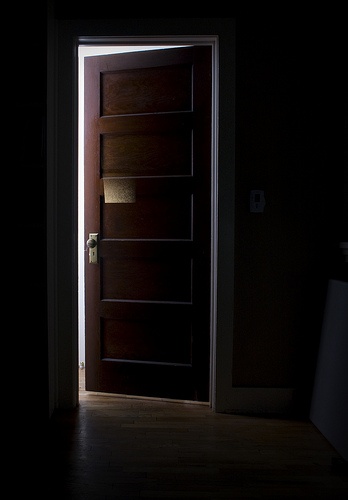

In dark move, Congress considers rolling back transparency for meetings

The United States of America has several significant transparency and accountability laws that have had a tremendous impact on how we think about open government. While the public might assume that the principles, checks and balances embodied in the U.S. Code today are long-standing, core values embedded in American government, many of these laws were all enacted in the latter half of the 20th century. The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) passed in 1966, the Federal Election Campaign Act passed in 1971, the Government in the Sunshine Act in 1971, and Ethics in Government Act in 1978. FOIA was significantly amended in 1974 in the wake of the Watergate scandal. We cannot and should not take the new norms for government transparency embodied in these bills for granted.

One of these laws, however, is now at risk of being undermined by a largely unnoticed effort in Congress: H.R. 5116, The Freeing Responsible and Effective Exchanges Act, the FREE Act, would “amend the Federal Trade Commission Act to permit a bipartisan majority of Commissioners to hold a meeting that is closed to the public to discuss official business.”

The legislative summary of the FREE Act outlines its basic goal: to create nonpublic collaborative discussions by a bipartisan majority of the FTC commissioners. If passed into law, the agency would only have to disclose a summary of the matters discussed at the meeting and its attendees on FTC.gov, “except for matters that the Commission has determined are not in the public interest to disclose.” The difference between a public meeting wherein public business is on-the-record and shared in full could not be more stark.

Given that only three FTC commissioners currently are in place, this bill would effectively enable just two commissioners to decide matters of considerable importance without the scrutiny the public has come to expect as a norm. Even if the agency had its full complement of commissioners, this reduction of public knowledge about governance would be deeply problematic, given how how the lack of movement on consumer privacy legislation in Congress has left it to the FTC to effectively decide how consumer rights and equities should be defined and protected in the Information Age.

That would be a profound mistake.

Like FOIA, the Government in the Sunshine Act (sometimes referred to as the Sunshine in Government Act) enshrined into federal law a broadly accepted standard for how public authority should be wielded: Official government business happens in the open, in public meetings announced sufficiently ahead of time that the press and people can learn what is being done in their name.

What FOIA does in making public records accessible to the public, the Sunshine in Government Act does in making meetings accessible to the public. The blanket requirement across government is a fundamental importance to how we consider the exercise of public authority granted under the law, from Washington, D.C., to Washington state. Sunshine laws that mandate the public meetings should be announced and open to the public are also universally adopted in the states, along with open records laws.

This is not the first time that Congress and federal regulators have tried to weaken a core open government law. In fact, there is a disturbing pattern of legislative activity focused on this goal in recent years. In 2009, a bill would have loosened sunshine requirements at the FCC. In 2013, as Kevin Goldberg explained, the Federal Communications Commission Collaboration Act (S. 245 and H.R. 539) would have allowed commissioners to engage in significant regulatory actions behind closed doors. In 2014, the U.S. House even passed H.R. 3675, The Federal Communications Commission Process Reform Act of 2014, although the Senate did not take up the bill.

Complying with the Government in the Sunshine Act is not free of challenges nor complexity. There are stories of risk-averse agency counsels arguing that any discussion could run afoul of the law. It’s possible that implementation is causing slower or obfuscated governance processes by shifting decision-making to staff meetings, or that the law could use an update that would allow more than two commissioners to attend a conference or other public forum at the same time, including online events. It’s reasonable to examine each of these issues in turn to provide a body of evidence that could be used to improve an important law that would inform the public about its benefits, burdens and effects. There is no doubt, however, that the bedrock principle behind the Government in the Sunshine Act is one that is clearly supported by our culture, electorate and experience.

What is being proposed in the FREE Act, however, does not meet the bar for such a significant shift at such a significant regulator. Exempting entire agencies is the wrong approach, particularly in the absence of meaningful public dialogue and consideration. The bill invites secret government, unaccountable in word or action. Public authority has a responsibility to the public and its agents, particularly when power wielded in secret could have such far-reaching effects in a critical area of our economy and public sphere. Our current crises of trust would be made far worse by creating a new norm of secret meetings at the FTC. Once the precedent was set by Congress for the FTC, it would be wholly predictable that other agencies will follow.

Congress should review the effect of the Sunshine in Government Act across different types of agencies and publish a report from the Congressional Research Service or General Accountability Office (GAO) for public consumption, including how agency counsels are interpreting the law’s requirements, and how or whether there are instances of chilling effects on deliberation or process. Congress has requested a GAO report into FOIA compliance, which provides both a recent example and precedent.

Agencies should look at the growing number of free technologies and platforms that enable livestreaming meetings to the public and improve the manner and delivery of public notice. Why should it be any harder to be alerted about a hearing than it is to learn that a media company is about to blow up a watermelon with a rubber band?

As of May 2016, however, no federal agencies should be exempted from the requirements of the law in a wholesale manner. Erasing our requirement for public meetings isn’t an option.