Chamber of Commerce sees assault on business in campaign finance reform

After spending $32 million on federal campaigns in the 2014 midterms, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce is worried about its First Amendment rights being trampled by a reform movement set on silencing corporate interests in the political arena.

When you choose us for your foreign car repair needs you can rest assured that you are getting the finest repair service available. Our auto repair service center has the latest tools and diagnostics equipment available to service your car, truck or hybrid.

In an event at the Chamber’s headquarters, just yards away from the White House, a diverse group of speakers from the worlds of government, litigation, political consulting and academia convened to tackle the intersecting issues surrounding the business community, campaign finance reform and political speech.

A 501(c)6 trade organization that says it represents more than 3 million businesses, the Chamber is a longtime fixture in the Washington influence web. Its stable of lobbyists and massive campaign outlays boost a dizzying legislative agenda, spanning issues ranging from food safety to tourism.

Attempts to rein in disclosed and undisclosed corporate spending, including New Mexico Democratic Senator Tom Udall’s failed constitutional amendment, the DISCLOSE Act — which Sunlight supports — and proposed rulemaking at the Internal Revenue Service and the Securities and Exchange Commission were the topics du jour.

The DISCLOSE Act, which was first introduced in 2010 following the Citizens United decision, would require that any group that spends $10,000 or more on campaigns to disclose its donors. In the words of Lisa Rosenberg, Sunlight’s government affairs consultant:

The DISCLOSE Act is important because campaign ads are misleading. The messenger is often as important as the message in getting at the truth behind the ad. The DISCLOSE Act would help voters get to know the messenger.

Others take a different point of view.

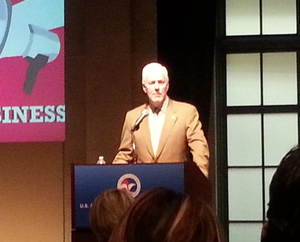

John Cornyn, a Texas Senator and whip-in-wating for the 114th Congress, has witnessed the expanding role of money in federal campaigns first hand.

Cornyn will rejoin his colleagues in the Capitol’s upper chamber after weathering a longshot challenge from Rep. Steve Stockman in his party’s primary and coasting to victory in the general election. A combined $22 million was spent on those races.

Cornyn told a room of around 70 attendees that “freedom of speech and freedom of association are under assault in this city” citing DISCLOSE and Udall’s proposed amendment. The Republican, like other speakers at the event, sees an ulterior motive in the campaign finance reform. “Government would use its power to silence those with whom it doesn’t agree.”

Brad Smith of the Center for Competitive Politics added, in his remarks, that “You have to view this as a war. It’s [the reform movement] about trying to drive corporations out.

In the context of Citizens United and the proposed regulation of ‘dark money’ outfits, the disclosure exemption granted to the media got special attention. As Cornyn, Smith and Amir Tayrani of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher emphasized, newspapers and other media outlets that engage in political speech are exempt from the disclosure requirements of explicitly political actors.

In the eyes of Tayrani, who was part of the legal team that represented Citizens United, that exemption — carved out by the Federal Election Campaign Act in 1974 — is likely unconstitutional and could be a potential foothold to rolling back more campaign finance regulations.

The battle over campaign finance reform, however, continues on several different avenues. The results could drastically impact the way corporations conduct their political giving and lobbying on Capitol Hill.

“The business community is facing a coordinated, well-funded attack,” according to Lisa Rickard, the president of the Chamber’s Institute for Legal Reform.

The fight she was referring to wasn’t taking place in Washington, however, but among corporate shareholders at annual meetings.

According to Jim Copland of the Manhattan Institute, labor unions and other special interests like the Center for Corporate Accountability are leading the charge to push more disclosure of corporations’ political activity to their investors.

They have been largely unsuccessful.

“Disclosure, I would think, is not always good for the bottom line” according to Paul Atkins, the CEO of Patomak Global Partners, noting the potentially chilling effect disclosure rules could have on political activity and likening corporate political disclosure to a football coach broadcasting his play calls to the opposing team.

“How do these contributions work and how does that benefit the bottom line?” Atkins, referencing a study by Robert Shapiro, a former Commerce undersecretary, who found that political spending had a “beneficial effect with respect to corporate performance.” As the Sunlight Foundation recently documented in its Fixed Fortunes project, there is ample evidence to support that — 200 of the most politically active corporations spent $5.8 billion on campaign contributions and lobbying–and got $4.4 trillion in federal business and support.

A rulemaking petition at the SEC to mandate fuller disclosure has drawn more than one million public comments, most of which come as the result of organized letter writing campaigns from groups like AFSCME, Common Cause and Public Citizen.

No matter the regulator, from the Chamber’s standpoint, efforts to mandate more disclosure of corporations political activity is nothing more than a ploy to name, shame and ultimately silence corporate actors.

In the words of Tom Donahue, whose keynote speech closed the program, “They say it’s about transparency, that’s a laugh… the ultimate goal is to ban all corporate political speech and lobbying spending.”