Sex and taxes: What the Romney returns and the Edwards precedent say about political slush funds

The cloak and dagger tale circulating on the Internet about a group of hackers who claim to have purloined old tax returns of GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney and say they will release them to whomever is first to pay their ransom suggests why a federal court case that absolved former Democratic presidential candidate John Edwards of campaign finance crimes was wrongly decided.

During his 2008 campaign, Edwards relied on the largesse of two wealthy Democratic donors to keep his affair with campaign worker Rielle Hunter secret. Edwards' campaign did not report the donations, nor did it report the payments made to support Hunter, who was pregnant with Edwards' child at the time. Had the public learned of Edwards' affair, his candidacy would most certainly have been over. Justice Department lawyers argued that Edwards, in benefiting from huge undisclosed financial support and undisclosed expenditures, flouted campaign finance laws that limit the size of donations and restrict the uses of that money to campaign purposes. The jury disagreed (as did many campaign finance experts) and Edwards walked free.

Fast forward to the 2012 campaign, and a story almost as bizarre as l'affaire Edwards. An anonymous group claims that it broke into a Tennessee office of PricewaterhouseCoopers, the accounting firm that prepares Mitt Romney's tax returns. The group further claims that they secured years of Romney's returns, and has offered to sell them to whomever can come up with $1 million in an Internet currency known as bitcoin. If no one antes up, the group says they will release the tax returns to the media.

Now, let's steal a few bases to make some assumptions: First, that the group has legitimately stolen Romney's returns (by no means certain, given some of the inconsistencies in their story); second, that the Romney campaign believes release of the returns would damage the campaign. We need not assume that Romney hasn't paid taxes for ten years as Sen. Harry Reid famously and without substantiation claimed, or that they show Swiss bank accounts, Cayman Islands corporations, Netherlands Antilles trusts and the locations of jars of cash buried in the backyards of Romney's many homes–it's enough for the Romney campaign to worry that discussion of his tax returns, his refusal to release them, their release by a third party and the inevitable vetting of them would distract from his message during a critical part of the campaign.

Though Romney's campaign certainly has enough money to pay the ransom, it's not clear that blackmail is a legitimate campaign expense, and in any case having a million dollar expenditure in bitcoin currency show up on a campaign finance report could be an even more damaging story than having the returns released. The same disclosure would be required if the Republican National Committee or a super PAC like Restore Our Future paid the ransom. But suppose a wealthy donor–an Edward Conard (who tried to use an LLC to anonymously donate $1 million to Restore Our Future) or a Sheldon Adelson (who has devoted a small fortune to supporting Republican candidates) or the Koch Brothers–decided to pay the ransom. For the sake of argument, let's also assume that they do so without telling the Romney campaign in advance, informing them only after their bitcoin transaction that the matter is taken care of.

Let's further suppose that, tax issue averted, Mitt Romney wins a narrow victory in November. How much access could that wealthy donor who paid the ransom expect? Not only had he helped the Romney campaign hide potentially damaging material that could have cost them the election, he would have in hand that material. Imagine the leverage that kind of relationship between someone who, the North Carolina jury told us, is not a campaign donor and need not disclose the payments that benefited the candidate.

Of course the potential for leverage the other way exists too. Suppose a Democratic donor acquires the material, and quietly informs the Obama campaign of the fact. Suppose he has issues before the Securities and Exchange Commission or the Internal Revenue Service or is seeking federal loans for a pet solar project, and would be happy to release the material should his own issues get a little presidential attention.

It would be fair to regard all this as conspiracy mongering were it not for the Edwards precedent, in which a candidate benefited from backdoor conduits and a donor slush fund that aided his campaign–with no disclosure.

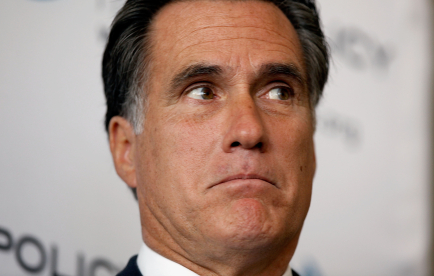

(Photo credit: Chip Somodevilla via iStockphoto.com)