ExxonMobil lobbies consumer agency on phthalates

(Updated 3/5/13)

Under heavy lobbying by ExxonMobil and other industry heavyweights, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) is nearly a year late with a mandated report on the possible dangers found in chemicals used to create plastic products from raincoats to "rubber" duck bath toys to shampoo.

Commission Chairman Inez Tenenbaum has stated that the report would be issued sometime this year, but a spokesperson, Scott Wolfson, was not specific about when, saying only that the commission would soon provide a plan for public review of the report. Meanwhile, advocacy groups are left wondering what the delay portends.

In 2008, Congress passed the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act, which banned three phthalates–the technical name of the chemical plasticizers–from toys and child care products. It also placed a temporary ban on three others, including DINP and DIDP, in which ExxonMobil does a robust business. These compounds appear in products from vinyl flooring to cable wiring. In addition, Congress ordered the commission to convene a special advisory committee of outside scientists, known as a Chronic Hazard Advisory Panel (CHAP), to study the possible health effects posed by the cumulative effects of exposure to phthalates from many sources. The panel's report was due last April.

A log of a meeting that month indicates that the expert panel is considering a permanent ban on DINP — a recommendation that would not be final until the Consumer Product Safety Commission issues its report. Four months later, a former Democratic congressman who heads American Chemistry Council wrote Tenenbaum arguing that the report was subject to certain administrative rules on peer review–a move that was seen by advocacy groups as a stalling technique.

Phthalates have long been a matter of concern for consumer and environmental health advocates and scientists. The critics point to studies showing possible effects on the reproductive system, links to obesity, and certain cancers, among other ills. Last week, an international panel of scientists convened by the United Nations and the World Health Organization said that such diseases are on the rise world-wide and expressed particular concern about the effects of phthalates on developing fetuses and children. They suggested governments should "ban or restrict chemicals in order to reduce exposure early, even when there are significant but incomplete data." Last fall, the advocacy center Center for Health, Environment and Justice released a study showing that 80 percent of children's back-to-school supplies sampled in laboratory tests–including backpacks, raincoats, notebooks–contained high levels of phtalates. The congressional ban on the chemicals' use does not extend to such items.

Phthalate makers argue that there's no proof the chemicals cause harm, and that where ill effects are detected, the doses required to produce them are far greater than what consumers are exposed to in daily life. The manufacturers provide reams of corporate-funded research to back up their assertions. Until recently, U.S. authorities appear to have bought into that argument, citing incomplete proof as a reason not to regulate, while the European Union has chosen a more precautionary approach, banning several phthalates in toys and childcare products in 2005.

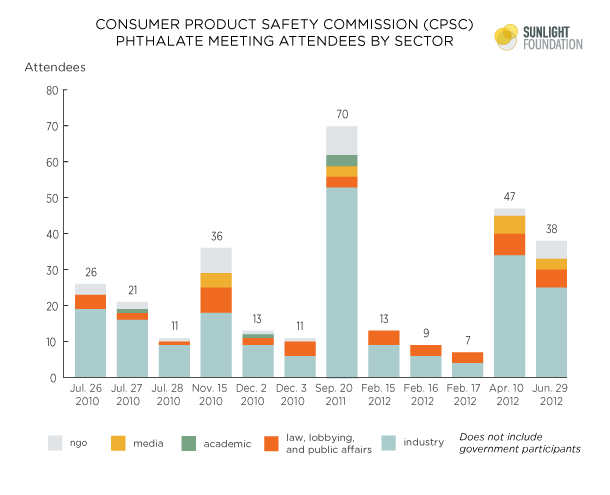

Since passage of the 2008 law, the Chronic Hazard Advisory Panel (CHAP) has overseen a dozen public meetings — some via teleconference and some at the CPSC headquarters in Bethesda, Md. — to hear various interested parties present science on phthalates, the most recent last June. An analysis by Sunlight of the affiliations of attendees at these meetings show that ExxonMobil and its law firm, Latham & Watkins, dominate, with representatives making 45 appearances over time. The American Chemistry Council, of which ExxonMobil is a prominent member, made 24 appearances. In contrast, two of the consumer advocacy groups most active on this issue, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and the Breast Cancer Fund made 12. Overall, industry groups vastly outnumbered other advocacy groups: 214 appearances compared to 30.

The public docket also shows that industry representatives have flooded members of the scientific panel with studies and internal analyses by corporate scientists that contest health effects associated with these chemicals. For example, this ExxonMobil review of science on DINP concluding that that there is a "robust data base for DINP demonstrating that those tumors in rodents are not relevant to a human cancer hazard assessment and that DINP is unlikely to cause cancer in humans." Another review presented in PowerPoint by the company states that "Toxicity studies since 2002 confirm that DINP/DIDP are safe."

The panel also heard from non-industry scientists whose studies raise concerns about phthalates, such as Shana Swan, who is studying the effect of phthalates on human health at Mount Sinai Medical Hospital and Environmental Protection Agency scientist L. Earl Gray. But staffers for groups on the other side of the phthalates debate say they overall felt outgunned. "[Industry has] unlimited resources, and I work for a $3.5 million organization on the left coast," says Nancy Buermayer, senior policy center for the Breast Cancer Fund. "I can't always fly in for a meeting." Sunlight's calls to reach ExxonMobil and the Chemistry Council went unreturned.

The industry's strategy of flooding the commission with favorable science is laid out in frank bullet points in a PowerPoint presentation by Eileen Conneely of the American Chemistry Council, created for a meeting of the Vinyl Products industry last July. Facing regulation by the Environmental Protection Agency as well as the CPSC– the industry would "defend and promote the benefits of… phthalates." The industry would "counter with science," and "counter with safety information and technical information on performance, benefits and cost." The presentation also cites industry projections that demand for plasticizers will continue to grow worldwide. Conneelly is listed as attending five meetings of the CHAP.

ExxonMobil and the American Chemistry Council, which is headed by former Rep. Cal Dooley, D-Calif., have been particularly aggressive, fighting hard not just on the science, but also on process. In March 2012, Latham & Watkins attorneys wrote this letter on behalf of ExxonMobil, protesting plans by the committee to submit the report for peer review to outside scientists before settling on a final draft. The following month, the committee indicated that it was considering a permanent ban on DINP, but noted that recommendations would not be final until the report was released. The following August, the American Chemistry Council made a similar pitch. Both letters argue that any peer review should be subject to Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which would open up the process to the public.

Raising the specter of OMB, however, was seen by the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Breast Cancer Fund as an industry delaying tactic. The phthalate critics argued in their own letter that no peer review was necessary under the law and that "[W]hile it might benefit the chemical manufacturers . . . to delay the CHAP report–and to have additional opportunities to try to change the outcome of a report it fears will not be to its liking–we believe that the Commission should act in the interest of public health first and encourage the CHAP to continue to conduct and complete its work transparently, scientifically, and as quickly as possible."

Wolfson, when asked how this issue was resolved, said that the commission would soon issue a plan for public review of CHAP's report, but that he could not provide details yet.

Update: Following publication of this post, an American Chemistry Council spokeswoman, Liz Bowman, wrote that the group does "not believe there is any scientific basis for restricting the use of phthalates as currently used in consumer products" but is committed that "the proper research and scientific reviews are completed to ensure public health and safety." The group continues to advocate that the report be subject to an outside peer review before it is made final.

In another incident earlier in the CHAP review process, the NRDC and the Breast Cancer Fund protested when ExxonMobil apparently pulled strings to present company-funded research by the Hamner Institute at a November 2011 meeting, despite the policy that all information at that point in the process be presented to the CHAP in written form only. The presentation, which focuses on DINP, concludes that the chemical does not significantly affect the male rat reproductive tract. Earlier the CHAP had denied ExxonMobil's request to present the information at the meeting, but the decision was reversed.

Congress' decision in 2008 to kick the issue of phtalates to study by the CPSC was something of a Pyrrhic victory for ExxonMobil, which had lobbied hard to save its products from regulation, observed New Yorker investigative reporter Steven Coll in his recent book, Private Empire, ExxonMobil and American Power. The law's "final provision on phthalates could not be described as a triumph for ExxonMobil–the consumer lobbyists had gotten more of what they wanted than the corporation," he wrote. But "ExxonMobil had a long record of persuading the Consumer Product Safety Commission to see phthalate regulation its way, and now the future of DINP manufacturing would be back before the commission, with ExxonMobil's lobbyists once again involved in a detailed review of phthalate science and risk mananagement."

Coll details how ExxonMobil had first tried to save DINP from regulation under the legislation, sending troops of lobbyists to talk to Capitol Hill staffers. The lobbyists showed PowerPoints making the case that the compound is not only not harmful but essential. They carried props such as iPod earbuds, pointing out how they contain the chemical. The decision came down to Rep. Joe Barton, R-Texas, and Rep. John Dingell, D-Mich., who were hammering out an agreement in a conference committee on the legislation. Barton has benefitted from more than $70,000 in campaign contributions from ExxonMobil's PAC and employees over the years, according to Influence Explorer. Dingell, who has gotten more than $15,000 over the years from the company's PAC and executives, convinced his Republican counterpart to accept a compromise — in the interest of getting the legislation through, Coll reported. The deal: temporarily banning some phthalates and kicking the final decision to the Consumer Products Safety Commission.

ExxonMobil was successful in convincing the CPSC not to regulate DINP on an earlier occasion, Coll reports. In 1998, following a petition filed by several public interest groups demanding that DINP be banned in children's toys, the commission convened another hazards panel and industry offered some of the same arguments they are today. "Throughout the commission's review, ExxonMobil scientists and lobbyists argued that DINP was safe enough to be used because the dangerous dosages seen in the rat studies were much, much higher than those that would realistically be encountered by children," Coll wrote. The commission voted in 2002 to deny the petition.

On February 14, the CPSC published final rules in a related matter, seen here on Sunlight's Scout tool, that set out guidance for an exemption from the phthalate ban for parts of toys or child care items that are not "accessible to a child through normal and reasonably foreseeable use and abuse of such product."

(Contributing: Jake Harper and Jennifer Cheng)