TV stations ignore ad disclosure requirements

|

|

What the law requires

What advertisers file

Here are some examples of "disclosures" that fall well short of the standards outlined above in McCain-Feingold law:

- The only name (and signature) on this Susan B. Anthony list form is Pam Mello. She's vice president for media services at Design4 Marketing Communications, according to her web bio.

- This form from Freedomworks has no names on it at all. A box indicating this is an issue of national importance is checked, but the issue listed is just "Freedomworks".

- This form from Independence USA at an Orlando, Fla. station doesn't list a candidate (although the group supported Democratic candidate Val Demings). The name listed on the form is Jeff Scattergood. He works at Abbar Hutton Media.

A decade after a landmark campaign finance reform law mandated that TV stations collect the names of board members or executive officers of independent groups running political ads for federal candidates or any "national legislative issue of public importance," records show broadcasters often ignore the rules.

Spot checks by the Sunlight Foundation found numerous instances where political advertisers did not provide information required by the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Finance Reform Act (also known as the McCain-Feingold law after its authors, Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., above left, and former Sen. Russ Feingold, D-Wis.,above right). These requirements have become particularly important in the wake of the Supreme Court's 2010 Citizens United decision, which gave rise to shadowy outside political groups organized as "social welfare" non-profits and therefore not required to disclose their leadership to the Federal Election Commission. Public tax filings with this information often don't arrive until years later.

As a result, the disclosures that McCain-Feingold requires advertisers to make at television stations have become the only means of determining who is behind the nonprofit groups that pumped more than $300 million into the 2012 campaign. But the Federal Communications Commission, which is in charge of enforcing the law, so far has not taken action against stations that appear to have flouted it.

In some of the records examined by Sunlight, advertisers explicitly refused to provide the required information but were still allowed to place their ads. In others, they complied with misleading language in the most widely used form for reporting information on political advertisers. Called the NAB form because it's published by the National Association of Broadcasters, it invites filers to list the name of an "authorized agent" instead of the groups' principals. That undercuts explicit requirements in the McCain-Feingold law (See inset at right for the relevant passage).

The distinction is significant: An "authorized agent" can be (and often is, in the filings Sunlight reviewed) a professional media buyer who works for dozens of committees and whose name reveals nothing about a group's ideology or funding sources. The identities of a group's officers or trustees generally are much more informative.

Stations, which are supposed to collect the information, have little incentive to pick a fight with advertisers who are paying top-dollar for air time, notes Meredith McGehee, policy director of the Campaign Legal Center.

"Look they made billions of dollars, much of it from the super PACs, so why bite the hand that feeds you?" she said.

Developed decades ago, well before enactment of McCain-Feingold, the NAB form nowhere indicates that the information it requests falls short of the law's requirements. As a result, many political advertisers fail to provide the information that the law requires.

Disclosure gap

The extent of the disclosure gap has become visible for the first time thanks to a 2012 decision by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to make network affiliates in the nation's top TV markets post the political ad files online. But if the nation's telecommunications watchdogs have served as champions of online disclosure, they seem less comfortable with the role of election law enforcer that has been foisted upon them by the changing campaign finance law.

An examination of the FCC's web docket reveals little evidence of any aggressive policing of the political advertisers. In just over 200 public file enforcement actions taken since 2000, and online here, the word "political" appears in 13 (the public file includes other information besides political ad disclosures). The only punitive actions taken (typically fines of $2,000-$10,000) came when the entire file was missing, often along with other public material. Asked to identify any enforcement actions taken on the basis of information missing from political files, the FCC press office declined to answer directly, but made clear it isn't actively auditing these papers. "The commission routinely relies on complaints…. in enforcing the political programming rules and statutory provisions," the office wrote in a statement.

There may be a simple explanation for a lack of complaints: while the ad documents are officially public, until last year the only way to see them was to request them, in paper, by visiting individual stations. Beginning last August, however, stations in the nation's top 50 TV markets affiliated with broadcast networks ABC, NBC, CBS and FOX–about 10% of stations overall–had to begin posting these documents on the Internet. Putting these files online, the FCC statement noted, may help identify scofflaws: "Any complaint filed with the Commission concerning compliance with these rules will be promptly considered.”

Still, the FCC, which needs to work closely with broadcasters on a wide range of technical issues, is in an awkward position vis-a-vis the industry it is supposed to regulate. Earlier this year, the NAB took the agency to court over the FCC's proposed order requiring even limited online posting of political ad files. It was a fight the regulators won, at least temporarily, in part by undercutting broadcasters' protests of an "onerous" paperwork burden with a system that made posting files was as easy as dragging them and dropping them on a computer screen. But ease for the broadcasters equals difficulties for the public. The Sunlight Foundation has organized those filings on Political Ad Sleuth, a tool that allows users to readily search the FCC database. But because stations can file the data as image files and use whatever forms they choose, there are significant barriers to sorting and making sense of this data.

Moreover, the way that the FCC implemented the order to post political files online has limited disclosure. The agency only required documents received after Aug. 1 to be uploaded, so groups that submitted disclosure information prior to that were omitted. It's impossible to tell by looking at web filings alone whether an advertiser failed to provide disclosure information or simply did so before Aug. 2.

The FCC wouldn't answer questions on the record. A spokesman who declined to be identified said in an emailed statement that the agency was committed to enforcing the law.

Non-disclosure disclosures

Even so, TV stations appear to be ignoring the disclosure requirements with impunity. Some examples that Sunlight found:

-

Freedom PAC spent $3.8 million on last November's election, most of it supporting former Florida Republican Rep. Connie Mack's failed bid for Senate. An employee at Tampa, Fla. TV station WFLA, however, noted in an ad document that the group "refuses to sign/fill out" a disclosure form. That didn't stop the station from selling air time to the group though. Public documents filed with the FCC show Freedom PAC spent at least $190,000 on ads at WFLA. And that doesn't include ads purchased before Aug. 2, when the new rule went into effect requiring major network affiliates in the nation's top 50 television markets to post their political files online.

Attached to Freedom PAC's NAB form on file at WFLA is another piece of paperwork, dated Sept. 5, that does list the group's treasurer and a Kansas mailing address. But the treasurer and mailing address given is for the wrong PAC. John Bradford, a rookie Kansas state representative who runs a state PAC in Kansas also called "Freedom PAC" says he's never run TV ads in Florida. Matt Oestreich, local sales manager at WFLA, acknowledged the mistake after Sunlight questioned the file. "This is the information that the agency gave," said Oestrich. The correct advertisher should have been a federal super PAC, also called Freedom PAC, with a New York address whose treasurer's name is Julie Pyun, Oestrich later clarified. The station has since corrected their file.

-

A non-profit group called "Checks and Balances for Economic Growth" placed ads across Ohio last October that called the Obama campaign's claim that coal miners were forced to attend a Mitt Romney campaign rally "complete lies" and featured a group of miners decrying the administration's "war on coal." A Politico story quoted a source who estimated the total buy at $900,000, and noted that ads would run in the Cleveland, Columbus, Charleston, Wheeling, Parkersburg, Zanesville and Youngstown markets, though it didn't identify who was behind the group.

Disclosure filings at seven of eight stations in the Cleveland, Cincinnati and Columbus markets didn't include the names of anyone associated with the group. Forms from WSYX, WTTE, WOIO, WBNS and WKRC were all signed by Greg Phelps, a media buyer at Strategy Group for Media, the group placing the ads. (Two other stations, WJW and WCMH didn't upload any disclosure forms at all). Additional ad request disclosure forms filed at WBNS and WTTE include a space for the names of the advertisers executives, but they were left blank. Only one of the seven stations, WEWS included a file with the group's executive director, Dan Perrin, listed.

Two of the stations (WTTE and WSYX) also uploaded an additional file called Leadership.pdf — but that file didn't disclose anything about the leadership of "Checks and Balances for Economic Growth." Instead it's a printout of the board of directors of Change.org, a site where political groups can upload their petitions and solicit support.

Though Checks and Balances for Economic Growth does have a page on the site, it seems unclear why this file was uploaded, and unlikely that Change.org, an overtly non-partisan organization with roots on the left side of the political spectrum, would have any substantive involvement in a group that was waging a political campaign against the president. Phelps, the media buyer who signed the form, said he didn't know about the leadership file, but added that it "must be a mistake" for it to have been included. "I'm not sure exactly what they would have uploaded; we provided the station with everything that they need," Phelps said.

Zoe Ann Del Borrell, public affairs manager at WTTE (which is operated under a local marketing agreement with WSYX), said that the station wasn't given a list of executive officers or directors of Checks and Balances for Economic Growth, and made a mistake when searching for the missing information. "We couldn't find anything about 'Checks and Balances'…. We looked for the information and it sent us to the Change.org [page] and that's what we downloaded," she said. Del Borrell offered to upload a full listing of the board of directors if Sunlight could locate one.

- Target Enterprises, which only works for Republican clients and whose leadership includes top-gun GOP operative Nick Ayers, has taken a stronger stand against transparency than most ad groups. In an April filing with the FCC, the group argues against putting the political file online, warning, among other things, of "compromised privacy rights and the chilling effect on speech that will be caused by placing the details of political ad buying online in real-time." The ad company that refused to fill out the NAB form at a Florida station for Freedom PAC, Target used its own ad purchase form when buying ads elsewhere. Although the form looks like the more widely used NAB form–with Target's logo on the bottom–it doesn't include a line for advertisers to list their representative. One such form filed at WTVT, another Florida station, doesn't even include the name of the group doing the advertising.

-

At KPNX in Phoenix, an ad reporting form for "National Horizon" disclosed only the name of the ad buyer and agency. After the ad buyer, the group's treasurer and the TV station were contacted by a reporter, a new file containing the name of the group's treasurer and executive director was uploaded. "It turns out that we had the form and in the flurry of paperwork we did not upload that particular form," explained station manager John Misner. The file, uploaded Feb. 12 — more than three months after Election Day — lists veteran GOP operative Nelson Warfield as treasurer. That doesn't match Federal Election Commission records, which list David Satterfield as treasurer. The difference is important, because it shows how groups required to file with the FEC hide their identities behind hired professionals. Satterfield works at Washington law firm Arent Fox in their government relations group; he's a paid treasurer for at least a half dozen different political action committeees.

Reporting forms were missing at KPNX for at least three groups that started advertising after the FCC required ad files to be uploaded: American Commitment, Friends of the Majority and Arizonans for Jobs. It wasn't until Feb. 15, after Sunlight began raising questions about the missing forms, that they were uploaded to the political file site. Two of the files, for American Commitment and Arizonans for Jobs, were both dated October, so they should have been filed online months ago.

The file uploaded by KPNX for Arizonans for Jobs lists only the group's treasurer, Gordon C. James–no other executive officer or board members are listed. The group spent about $100,000 supporting Arizona Republican Jeff Flake's successful bid for Senate. A phone number given on the form is for James' public relations firm, Gordon C. James Public Relations. Arizonans for Jobs' web site notes that "the board of Arizonans for Jobs is comprised of trusted Arizonans who control all expenditures and are responsible for approval of messaging," though it doesn't list their names. The only names given on the site–including James'–are listed as consultants. The PAC's biggest vendor: Target Enterprises.

Captive agency?

Some critics suspect the FCC's cooperative relationship with industry has made it, in the words of Campaign Legal Center's McGehee, "a captive agency," that views industry as a more important client than the public. Reformers had high hopes for FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski, McGehee said, "but the reality has been that when it comes to this particular arena, he's been AWOL." Nor do elected representatives charged with overseeing the FCC provide much incentive for the agency to do a more aggressive job, she added.

"All of those members of Congress go home and are incredibly scared of their local broadcasters," McGehee said. In court the agency's won-loss record has not been strong, and, perhaps as a result, the FCC's been "very timid at doing anything very muscular," she added.

Steve Waldman, who in 2011 was an FCC senior adviser and lead author of a report calling for the political files to go online, offered a more sympathetic view, describing the process for posting files online as a work in progress. The biggest problems, Waldman said, are the lack of data standards and searchability, a byproduct of the FCC's decision to let stations use their own paperwork to file reports.

"In general this should not be viewed as cast in stone and they should view their first whack at this as just a first step; now's the time to look at how it's been working and what sort of things have been discovered and move towards improving the system," said Waldman, now a visiting senior media policy scholar at Columbia's school of Journalism.

The vast majority of stations now required to post ad buy documents online use the standard NAB form to report who is purchasing "issue ads." The title is somewhat misleading, because any group that's not directly aligned with a candidate uses this form, including super PACs whose sole purpose is to support a candidate.

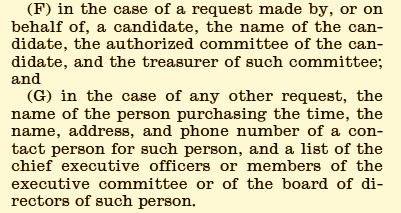

The language on the NAB form falls short of the McCain-Feingold law's disclosure standard. Section 504 of the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act says that television stations must include in their political file "a list of the chief executive officers or members of the executive committee or of the board of directors of such person" responsible for the ad. But the form put out by the broadcasters group says that "The names, offices, and addresses of the chief executive officers, directors, and/or authorized agents of the entity are named below (may be attached separately)." Nowhere does the form indicate that the names of executive officers and board members are actually required. For an example of the form and how it is filled out, click here.

Because there are no agency rules dictating how advertiser leadership must be disclosed, it doesn't necessarily have to be on the NAB form. Some stations add "client info sheets" or tack them on to ad contracts. In the online file, chaos rules — which suggests that far worse lurks in the many paper files that have yet to be uploaded. Only the biggest stations have to make their public files available online; if anything the files from smaller stations are likely even more error prone.

Ann Bobeck, senior vice president and deputy general counsel at the NAB, strongly rejected the idea that the forms gave cover for broadcasters to skirt the law.

"We have not directed our stations to collect less than what is statutorily directed," she said. Bobeck said the forms had been developed with input from FCC lawyers in the office of political programming and that the language mentioning authorized agents dates "to the best of our historical knowledge" to the presidency of George H.W. Bush.

That predates the McCain-Feingold law; at the time, there was no explicit legal requirement for disclosure of issue advertisers' executive officers and board members. A political file did need to be maintained however, and Bobeck characterized the language of the NAB form as a victory for transparency. "We weren't getting any signatories on our political forms at all, so that language, carefully crafted and negotiated with the FCC, in terms of getting a signature, was added in," Bobeck said. There was a revision of the forms in 2002, according to Bobeck. The current version, downloadable from the NAB's web site, carries a copyright date of 2011.

An FCC official, speaking on condition of anonymity, said that the there was no "formal" review process, and claimed the forms weren't "vetted". But FCC lawyers "really do give informal guidance," Bobeck said. "We do a lot of back and forthing and though they can't give any formal opinions they are very helpful and instructive about the information that they would like to see us collect for purposes of the public file," Bobeck said. "Their informal advice is not binding; it is certainly instructive about what they are looking for."

Decades after the "authorized agent" language was added, advertisers' reluctance to reveal their identies hasn't changed. Even today, "It's hard for [TV stations] just to get a signature out of the issue advertiser or the [advertising] agency and they do a yeoman's work trying to track down this information which often is not provided by anyone signing the document," Bobeck said, "and I will tell you, the accuracy of what's provided by the agencies is often not correct."

Matt Wood, policy director of Free Press, part of a consortium of public interest groups that has sued the FCC on public file issues, said that while he was unaware of the NAB's consultation with FCC, it's consistent with how the nation's communication watchdog operates. Informal consultation by NAB lawyers with FCC amounted to "a wink and a nod" from the agency that made insufficient disclosure "the law of the land," he said.

What good disclosure yields

When disclosure on who's behind political ads has been made according to the McCain-Feingold requirements, it has yielded important insight into who's behind the so-called "dark money" invested by groups that don't disclose to the Federal Election Commission. Last September, the investigative news non-profit ProPublica reported on a little-known group called the Government Integrity Fund, that spent more than $1 million on last year's Ohio Senate race, backing Republican candidate Josh Mandel. The group doesn't disclose donors, used only a post office box, and the only name that appeared on public documents was that of a lawyer who said he had no role in the group's affairs. But an ad disclosure document filed at a TV station helped show that the group "is run by a state lobbyist who in turn employs a former top Mandel staffer."

The document that ProPublica found, however, wasn't the standard NAB form. Instead it was one put out by Hearst Television Stations that didn't give the option of listing an authorized agent. Consistent with the law, the form requires the board of directors or executive officers to be listed.

The Supreme Court addressed objections to collecting ad buys in McConnell vs. FEC, a 2003 suit filed by current Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky, among others. Critics protested that the requirement was tantamount to forcing disclosure of campaign strategy. Writing for the court, Justice Stephen Breyer noted that the rule "requires disclosure of names, addresses, and the fact of a request; it does not require disclosure of substantive campaign content." Breyer opinion also pointed out the the FCC had authority to write regulations implementing the law.

Sunlight's findings about the shortcomings of political ad disclosure come as Democratic congressional leaders, seizing on a Government Accountability Office report issued last week, are asking the FCC to step in and do what neither the Federal Election Commission nor Congress have so far been willing to do: write rules that require disclosure of who pays for political ads.

A proposal backed by former FCC commissioner Michael Copps, among others, would require political ads to identify those who paid for them — including ads run by groups not otherwise required to reveal their donors. Copps would require a listing the names, on screen, of anyone who provided 25 percent or more of the funding for the group running the ad.

Instead of "'Citizens for Cherry Pie and Motherhood and Pancakes in America' or something like that you'd actually put the names," he said. The approach suggested by Copps, a Democrat who now heads the Media and Democracy Reform Initiative at Common Cause, has backing from House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., and others in her party.

The Democrats' proposal draws on statues allowing FCC to force stations to "fully and fairly disclose the true identity of the person or persons, or corporation, committee, association or other unincorporated group, or other entity” buying an ad. The rationale is simple, Copps said: "those who are using the public airwaves have to disclose who's paying for an ad." Although Thursday's GAO report reiterated that authority, FCC hasn't written rulesto implement it, and any new rules would likely face a legal challenge. And, as Sunlight's investigation has shown, the FCC so far has been reluctant to exercise the much more explicit authority it has under McCain-Feingold to make public the identities of individuals behind political ads.

Asked about the FCC's mixed record enforcing rules, Copps agreed that rules alone aren't enough. "There's no use having rules if you don't enforce them," he said.

(Photo credits: U.S. Congress)

This post has been updated with additional information about the "Freedom PAC" running ads in Florida.