OpenGov Voices: Lack of Transparency and Citizen Disenfranchisement

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed by the guest blogger and those providing comments are theirs alone and do not reflect the opinions of the Sunlight Foundation or any employee thereof. Sunlight Foundation is not responsible for the accuracy of any of the information within the  guest blog.

guest blog.

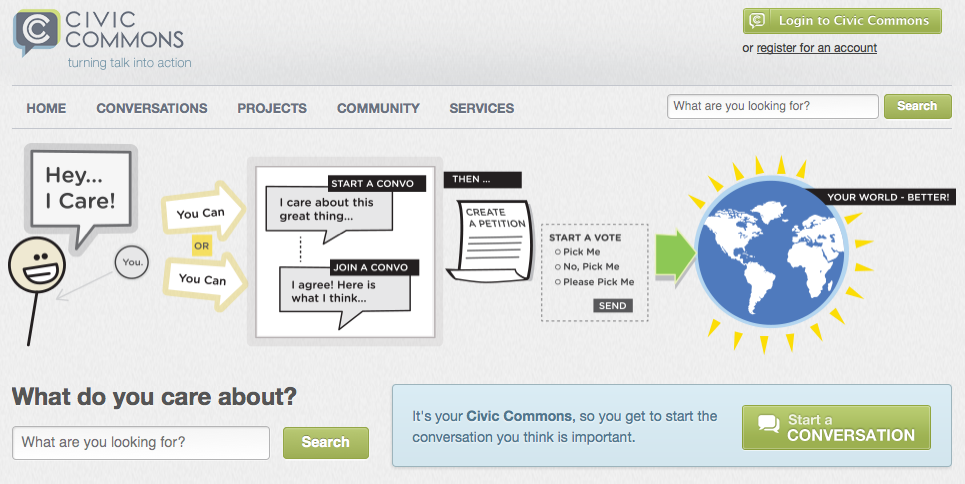

Dan Moulthrop is a co-founder of The Civic Commons, a social media environment group designed explicitly for civil civic dialogue and brings communities together with conversation and emerging technology based in Cleveland, Ohio He is also CEO of The City Club of Cleveland, the Citadel of Free Speech for more than 100 years.

I’ve long been obsessed with maps. When I was a kid on road trips, I loved tracking our journey in the road atlas. When I lived in Brooklyn in the 90s, I covered my bedroom walls with AAA state maps with my then-recent three month cross country journey traced out on them. Maps always provided me with a way to locate myself in space and a way to understand my trajectory. In the last couple of years, I’ve started to see them differently. The maps I’m thinking about don’t locate us or help us see a trajectory of growth or journey. They trap us. Specifically, they keep us attached to elected representatives that don’t often have our best interests in mind.

Residents of Cleveland, Ohio, were just subjected to a redistricting exercise. I say subjected to because very few of them participated in the exercise. The last census triggered a charter-mandated remapping of ward boundaries, and, given the population decline, city council is to be reduced by two seats. The need for this had been in front of city leaders since census results were released, but there was no comprehensive, strategic public engagement process to discuss what factors ought to be taken into account as new ward configurations were considered, no draft maps shared with the public, no clear process for providing input. Instead, Cleveland’s city council president worked with consultants behind closed doors and met with his colleagues on council individually to make deals and divvy up the city’s population.

It has been said that we live in a time when voters don’t pick their representatives; rather representatives pick their voters. In this case, the council president appears to have picked voters for his colleagues.

I don’t actually know if this map will be good for Cleveland or not. Nobody knows. Those who voted for the first version of the map have had to backstep a little when Cleveland’s small but significant Hispanic community challenged the map as a possible violation of the Voting Rights Act. Now that that detail has been addressed, for all we know, this could actually be the best map we ever could have hoped for. Here’s the problem: we’ll never know.

Drawing the boundaries that define electoral districts is literally what democracy is made of. These geographic units are the building blocks of government. They determine which particular voters will be able to cast ballots in which particular races. When the process that creates these maps happens behind closed doors, we have no way of knowing the motives of the consultants and those they serve. Is there a desire to create politically diverse or homogenous districts? Are they trying to keep neighborhoods intact or break them apart? Are they trying to pack a district with loyal voters or seeking to create a competitive opportunity?

When there is little transparency, good government advocates can only assume the worst–that citizens are being disenfranchised.

What’s so disheartening about this happening in Cleveland is that Ohioans just saw this same thing play out at the state level last year by Republicans in the statehouse tasked with drawing new congressional district boundaries. (The Cleveland process was led by members of the Democratic Party.) The map GOP state legislators settled on is problematic at best. Ohio is a swing state, roughly 50 percent Democrat and 50 percent Republican. A majority of voters cast a ballot for President Obama. Yet our congressional delegation is 75 percent Republican and 25 percent Democratic. It doesn’t quite make sense, but it’s made possible by a map that cracks Democratic-leaning urban areas, and creates safety for GOP incumbents with vast swaths of rural voters. It was the product of closed-door sessions and, like the more local example, the recipient of no small amount of criticism and the catalyst for failed redistricting reform efforts.

We can do better. I’ve written about this elsewhere, and there are people smarter than me giving this a great deal of their energy. At The Civic Commons, we’re deeply interested in providing the space and tools for civil civic dialogue that can help communities solve the problems and meet the challenges they face. Elected representatives charged with the responsibility for creating new maps could easily, and without any cost apart from time, launch an online dialogue with the community about their concerns and their hopes. As the good folks at the National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation say, you can either engage the public or “decide and defend.” And when you engage the public online, it’s asynchronous, which means everybody with Internet access can participate whenever they have time. And any elected official who thinks there isn’t time to do that on the front end, should ask if there will be time and political capital to spend later on to defend the closed door process.

Though at one time we may have believed our elected representatives were capable of drawing new district maps with our best interests at heart, there’s little reason to believe that’s the case today. When it comes to conversations about how voters are divvied up, we should insist that we all be a part of that conversation.

Interested in writing a guest blog for Sunlight? Email us at guestblog@sunlightfoundation.com