Lack of transparency likely to tarnish Hungarian election

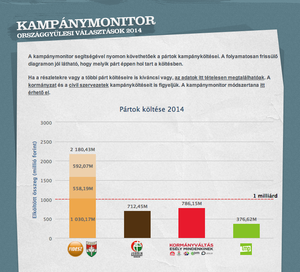

When Hungarians go to the polls on April 6, their knowledge about the parties and candidates will have been shaped by a brief but intense campaign season in which political ads paid for by “phony civil organizations” — we’d call them fake social welfare groups in the U.S. — literally papered the streets of Budapest. A collaboration of Transparency International (TI), Atlatszo.hu (a Hungarian investigative journalism web portal) and watchdog K-Monitor pieced together data demonstrating that the ruling party is winning the money race, outspending all other parties combined.

But as troubling as the uneven expenditures might be in terms of ensuring all voices are heard in the Hungarian election, even more troubling is that ruling party Fidesz’s expenditures are twice the legally permitted amount.

Hungarian “dark money”

What went wrong? Hungary has a new election law that was supposed to address the country’s long battle with corruption in part by limiting campaign spending through publicly funding campaigns. Each party receives a set amount of public funding and each candidate is entitled to a supplemental amount. The parties are also entitled to a limited amount of private money from wealthy individuals. But, as a result of loopholes in the law, the upcoming elections will be shaped and scarred by an influx of secret outside spending: Hungary’s own dark money problem.

Whereas Americans are bombarded with dark money attack ads on television, in Hungary the problem appears to be on streets lined with attack billboards and posters. According to reports, the attack billboards skew heavily in favor of the ruling party, describing the opposition as clowns and crooks.

And, like dark money ads in the U.S., the Hungarian ads are paid for not by the party or candidate, but by an opaque outside group, the Civil Alliance Forum. Supposedly “independent,” the Civil Alliance Forum is apparently funded by wealthy backers of Fidesz, undermining the public funding system and leaving opposition parties without major outside financial backers at a distinct disadvantage.

Inadequate disclosure

In addition to the outside money problem, Hungarian elections are suffering from a disclosure problem. Even with the new laws, party financial statements are hard to access and disclosure of private funding is spotty at best. To create their new website — Kepmutatas.hu (Hungarian for hypocrisy) — TI, Atlatszo.hu and K-Monitor had to piece together data about advertisements, media appearances, direct marketing and other expenditures, all without the benefit of publicly disclosed campaign spending reports. According to an OSCE report, there are no reporting requirements before Election Day. Moreover, while individual candidates must eventually provide more detailed spending reports, the parties do not. Transparency is further thwarted by legislation ordering the cost of advertising on public billboards need not to be disclosed — a rule the U.S. National Association of Broadcasters must be salivating over.

A cynical electorate

A recent public opinion poll commissioned by TI found that only 8% of Hungarians are counting on a clean election, and a majority believes that illegal funds are financing the campaigns. In response, TI, K-Monitor and Atlatszo.hu have developed an anti-corruption minimum program — www.ezaminimum.hu — to recommend measures that may be taken against the misuse of public funds, including reform of party and campaign financing, public procurement, asset declarations and conflict of interests.

It is hard to trust any government decision if the means by which those elected came to power is viewed as illegitimate. The Hungarian example is just the first of what will likely be a long line of opaque political finance systems that demand a transparency overhaul in order to improve overall trust in government, improve decision-making by elected officials and limit corruption.