“Why would a little disclosure be better than a lot of disclosure?”

Rep. Chris Van Hollen, the ranking Democrat of the House Budget Committee, wants dark campaign money to see the light of day — but he won’t be holding his breath.

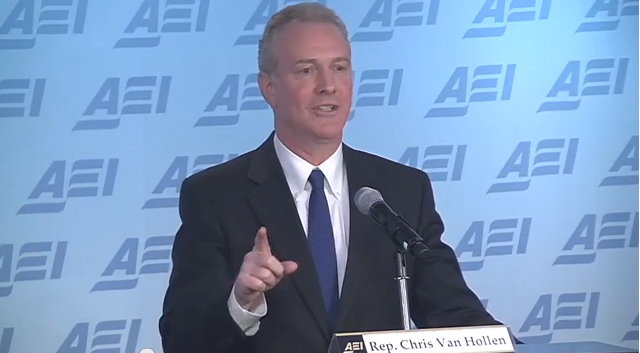

In an address at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), Van Hollen, a former DCCC chair and architect of the DISCLOSE Act, was not overly optimistic about the bill’s chances for success, but pointed to recent developments at the IRS as the more likely avenue for reining in dark money. Van Hollen and several watchdog groups dropped a lawsuit against the agency after it announced the beginning of a rulemaking process to define the permissible political activity of so-called “social welfare” groups, the main nonprofit vehicle for undisclosed political spending.

The Maryland congressman is one of the House’s most vocal advocates for opening the books of political nonprofits, which are popular, at least in part, because they shield donors’ names from the public. Van Hollen defended the push for greater transparency of these social welfare groups and responded to arguments from prominent opponents of the Act, among them Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky.

Political nonprofits — generally organized under Section 501(c)4 of the Internal Revenue Code — exploded in popularity (see OpenSecrets.org) after the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision allowed corporations to make independent expenditures to influence campaigns.

MORE: See Sunlight’s reporting on dark money.

For the bill’s sponsor, the matter is simple: “The public should be informed about who is spending vast sums of money to influence their decision to vote for or against candidates for public office,” and while past iterations of the DISCLOSE Act failed on party lines, Van Hollen said he sees bipartisan support for the efforts among members of the public — and the Supreme Court. He cited opinions ranging from Buckley v. Valeo to Citizens United in which justices on the nation’s highest court supported disclosure as an effective measure against corruption and undue influence of major donors.

Others see a political motive behind efforts to ferret out dark money.

In a 2012 talk at AEI, McConnell lambasted would-be reformers as administration stooges that would use donor transparency laws as a tool for harassment and intimidation — stifling First Amendment protections of free speech. More recently, news that the IRS targeting of conservative nonprofits for increased scrutiny of their political activities has some worried that the DISCLOSE Act would unfairly target right wing groups.

“His analysis, to put it diplomatically, is a bunch of nonsense,” Van Hollen said of the Senate’s Republican leader. Though McConnell has been one of the most outspoken critics of the reforms in recent years, Van Hollen pointed to a 2000 interview on Meet the Press when the Kentucky conservative defended his vote against a bill requiring all 527 political groups (like PACs, super PACs and candidate committees) to disclose their expenditures. His reasoning? The bill did not go far enough: “Why would a little disclosure be better than a lot of disclosure?”

As for the charges that the legislation would lead to harassment of donors for political speech — a worry shared by other former proponents of transparency — Van Hollen argued that the attack ads like those recent targeting conservative megadonors the Koch brothers are “…part of the rough and tumble of a vibrant democracy and a spirited debate.” The FEC has granted a reporting exemption in the past, he noted, to the Socialist Workers Party, whose members faced “a long history of threats, violence and harassment.” In November of last year, the FEC’s commissioners did not extend the same exemption to the Tea Party Leadership Fund, by a vote of 3-2.

The DISCLOSE Act of 2013 has not seen action in the House since Jan. 3 of last year. As for the ongoing debate on the bill’s repercussions on free speech: “If Sen. McConnell wants to come back here to AEI… to discuss this matter, I would be happy to join him here at this podium.”