Money can’t buy you the NRA

Former New York Mayor and billionaire philanthropist Michael Bloomberg recently committed $50 million to a gun control effort to “outmuscle” the National Rifle Association (NRA). According to Bloomberg, the money has a simple goal: “We’ve got to make them afraid of us.”

The new effort, however, misunderstands the NRA’s two sources of success.

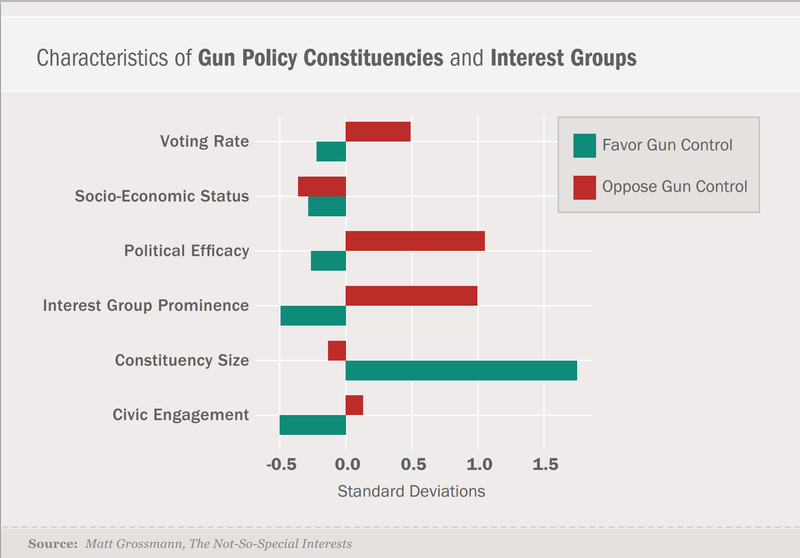

First, the NRA’s important role in politics is built on an active constituency. In my first book, The Not-So-Special Interests, I compare the supporters and opponents of gun control in the American public to 138 other public constituencies of interest groups. The graph below reports some comparisons, reported as standard deviations above or below the mean for constituencies. My measure of interest group prominence comes from media mentions and congressional testimony by the organizations on each side, but every measure shows the same unsurprising result: Organizations like the NRA are much more prominent than organizations that favor gun control, like the Brady Campaign.

Constituency size is not the reason: The subgroup in the American public that regularly opposes gun control is substantially smaller than the subgroup that regularly supports it.

Both supporters and opponents of gun control are lower in socio-economic status than other mobilized groups. The real differences come in indicators of the relative political engagement of the two sides: Gun control opponents have higher efficacy (they believe that their actions will influence government), civic engagement (they join more organizations) and voting rate. These differences have been consistent for decades and are not easily changed.

This matches evidence from other research. Gun control opponents are consistently more politically active and engaged. Gun control supporters have mobilized inconsistently in a series of broad, but mostly short-lived, efforts.

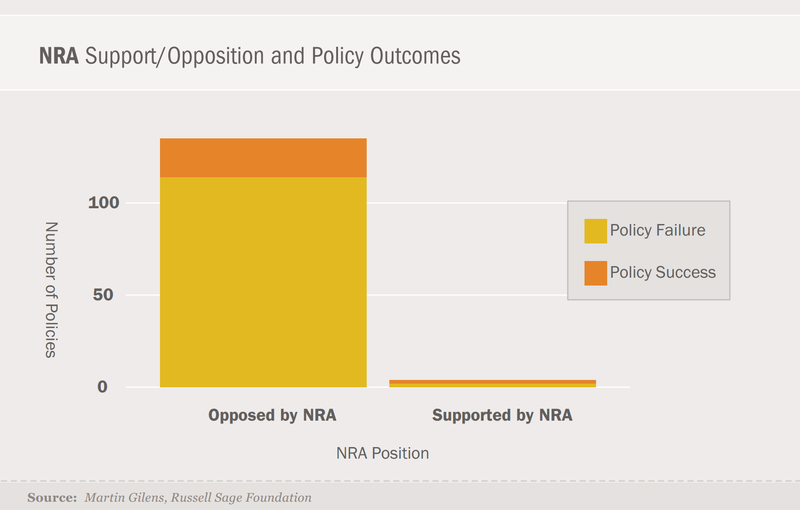

The second reason for the NRA’s success is that it is usually playing defense: It seeks to block legislation rather than support new laws. The graph below reports data collected by Martin Gilens on the NRA’s positions on policy change and its success. The NRA has supported 4 policy changes and opposed 139 policy changes (among the 1,200 he studied). Their success rates are 82% for blocking change and 50% for supporting it.

The NRA’s success is part of a broader pattern. Interest groups that favor the status quo have a major advantage because blocking change is much easier than getting a bill passed two chambers of Congress and signed by the president. Even if Bloomberg were to build an organization as strong as the NRA, such an organization would still face the difficult task of advocating new laws rather than blocking them.

Perhaps Bloomberg should have just given his $50 million to the Brady Campaign. My new book, Artists of the Possible, covers the history of major policy change: It is nearly always a slow, arduous process of internal coalition building between interest groups, legislators and administrators. Few interest groups have the capacity to bring about major policy change; they almost always rely on ties to policymakers and longstanding reputations rather than new efforts to direct money to campaigns. Although the Brady Campaign is less successful than the NRA, policy historians credit them with influencing major new laws. Even though the Brady Campaign’s efforts usually fail, working through organizations with established reputations and histories of involvement nearly always beats new efforts to dislodge existing groups or mobilize silent majorities.

The effort to enact gun control will be an uphill battle no matter how it is pursued. Bloomberg’s effort has only one thing going for it: his money. The Brady Campaign not only has a better reputation and a long history of policy involvement, it also serves as a better spokesperson for the cause.