OpenGov Voices: Hartford’s new open data portal

Hartford is a small city. Its footprint of just 18 square miles – one-third the size of Denver International Airport – is home to 125,000 people. Hartford was the most affluent city in the country more than a century ago, but has lost a third of its population since the 1950s and now has a poverty rate nearing 40 percent.

It will take a long time to address the many challenges that face Hartford and other small, post-industrial cities. But open data is one small way to enable progress and Hartford recently joined the ranks of cities with open data portals.

The Hartford team working on open data went from zero to launch in a matter of months. An executive order from the mayor provided a mandate for city departments and made Hartford a leader in the state, which created its own open data portal earlier this year. The open data team from the City pounded the pavement to hear what neighborhood groups wanted to see and what they expected.

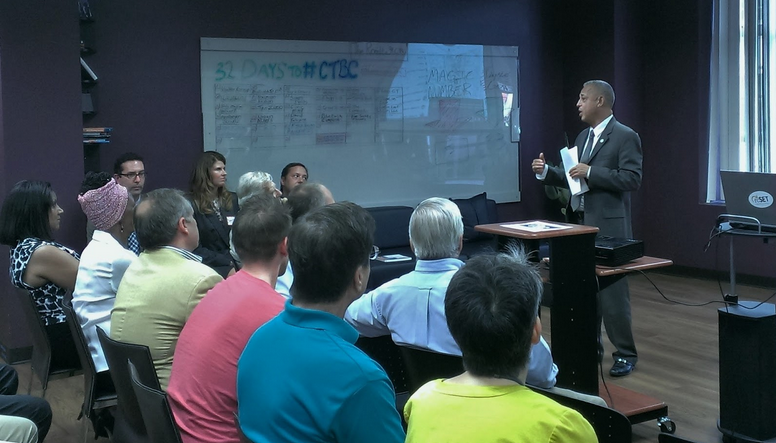

Working in a small city makes it easier to get the word out. Designers and developers attended a launch for the open data portal with the Mayor at reSet, a co-working space and hub for social entrepreneurs. Nonprofits, journalists, policymakers and academics also attended a series of workshops on open data and visualization tools organized through Trinity College. The launch was covered in the Hartford Courant, the Hartford Business Journal and local news, with a map of crime data from the Courant’s Data Desk featured as a Tableau Public Viz of the Day. The hyperlocal news site Real Hartford mythbusted by digging through data on bedbugs, drug arrests and crime in parks. And open data made it on the 11 o’clock news, at least for a minute.

It may be easier to make connections and cut through bureaucracy in a smaller community. But there are limitations. A city collects data within the city boundaries. People’s lives rarely align neatly with official boundaries, especially in a small city.

For instance, crime data looks at crimes committed in the city. We know from historical data on Hartford, however, that many crimes that occur within the city limits lead to arrests of non-residents, as Real Hartford points out. Non-residents are arrested for violent crimes in Hartford more often than the residents of any single neighborhood.

Schools present the same issue in Hartford. Due to the landmark desegregation lawsuit Sheff vs. O’Neill, students in the Hartford region have a range of public options for schooling–local school districts, magnet schools, charter schools and open choice programs. Jack Dougherty from Trinity College explored neighborhood data from the open data portal to look at declining enrollment in Hartford Public Schools from Hartford neighborhoods. But open data on one district doesn’t tell us if Hartford residents are choosing other magnet or charter schools in the region or moving to other towns for school. Understanding the dynamics in full requires regional schools data and that requires interest and support for open data across communities.

This same dynamic is pervasive for small cities like Hartford. Data on the city alone only tells part of the story about crime, about schools, about transportation and jobs. While the Connecticut Open Data site shares statewide data and the City of Hartford is the first of the 169 municipalities in the state to follow suit, the underlying issues faced by Hartford are grounded in regional inequalities. Depending on how one draws the boundaries, the Hartford region covers some 30 to 40 individual towns surrounding Hartford. Adopting open data policies more broadly in the region will face challenges with costs and skills of new technology, consistency and coordination in reporting and, most importantly, leadership and political will in these towns.

Hartford got it done, even in “The Land of Steady Habits.” Open data worked in Hartford when advocates within the city were able to align with leadership to move forward quickly. Can we find the same ingredients in the communities economically and historically connected to small cities like Hartford? Can a region like Metro Hartford get it done?

Scott Gaul is Director of the Community Indicators Project at the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving, the community foundation for the Capitol Region of Connecticut and a member of the advisory committee for Hartford’s open data portal. Read the Metro Hartford Progress Points report here. Scott can be reached at SGaul@hfpg.org and at @MetroHtfdProgPt.

Interested in writing a guest blog for Sunlight? Email us at guestblog@sunlightfoundation.com