In search of not-so-lost time: What transparency can tell us about history, race relations and Ferguson

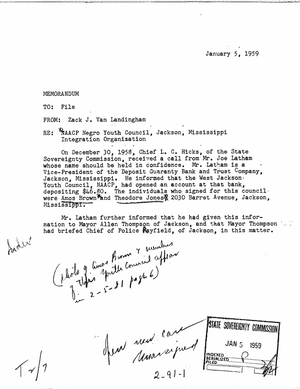

In 1958, Mississippi teenager Amos Brown, a youth activist with the NAACP, opened a bank account at the Deposit Guaranty Bank and Trust Company, in which he and another activist deposited $46.80. This was deemed such important information that the vice president of the bank, Joe Latham, told the mayor, who then briefed the chief of police.

The incident is recorded in a memorandum to file for the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission. Founded in 1956, following the Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 decision to desegregate the nation’s schools, the Commission was established supposedly to protect the state from federal encroachment. In fact, it became a spy agency, recording information about Brown and other activists who were working to bring civil rights to the African-American community.

The Commission remained in force until 1977, when the legislature approved a law that abolished the agency. The Commission’s records were to remain secret for another 50 years, keeping them from the public until 2027. The documents were contained in “six filing cabinets, two unsealed pasteboard boxes said to contain fiscal records, two separate folders in a manila envelope, and a bound volume which was said to be a minute book.”

But the ACLU didn’t think they should remain secret. In 1977, the group filed a class-action lawsuit that charged that state agencies had illegally followed the activities of citizens. It wasn’t until 1998 that U.S. District Court Judge William H. Barbour, Jr. (a Ronald Reagan appointee and cousin of Haley Barbour, a former governor of Mississippi and former chairman of the Republican National Committee) ruled that all the records not involved directly in the litigation should be made public. These are now available, in searchable format, on the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. You can see them here.

This sorry episode in American history — and the importance of transparency in revealing it — provides some historical perspective as our nation confronts the bitter legacy of race relations following the shooting death of black teenager Michael Brown at the hands of a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo. This sort of transparency, won only because of a tough court battle, brings depth to our understanding of the past and can inform us in how to approach the future. It wasn’t that long ago that the simple act of opening a bank account by an African-American was cause for police surveillance. And, indeed, we are still grappling with the breadth of surveillance conducted now of American citizens revealed by Edward Snowden.

While these archives are well known among scholars of the civil rights movement, I stumbled upon them sideways, through a personal connection. In 1958, at age 32, my father, Sanford Watzman, wrote a story about Amos Brown for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, where he was a reporter covering the NAACP convention that summer. I came upon this story following my father’s death last July, while going through papers he saved. In the story my father wrote about Brown, the then 17-year-old talks about how his school back in Mississippi is inferior compared to the schools for whites. “One night the ceiling from the biology room caved in,” Brown told my dad. “The administrators tried to keep it quiet and didn’t tell the newspapers. I think they were in the position of being afraid to ask for too much.”

Brown is still very much alive, and indeed is now a board member of the NAACP and pastor of San Francisco’s Third Baptist Church. When I called him up, he not only remembered the story my dad had written, but told me that it has almost gotten him expelled from school. It was only a threatened lawsuit by Medgar Evans that got him reinstated at Jim Hill High School, where he graduated in 1959. His full story is archived at the Library of Congress in this oral history. It is a fascinating read.

Brown told me about the Sovereignty Commission and, thanks to a colleague who was in Mississippi when the files were opened, how he learned about the extent the Commission had followed him, a teenager at the time. The files include another newspaper account reporting on how the NAACP had charged that Brown was kept out of school because of the interview he gave to my dad. They record the bank account. There are copies of programs of meetings where he spoke. They record his arrests for sit ins. There’s an account of how he “caused quite a stir-up” at the university hospital when he challenged a white doctor who referred to a “colored” patient as “boy.” “He is a full-fledged agitator,” reads the memo.

There are plenty of people who wanted to keep these records secret. But now anybody who can connect to the Internet can find them and learn about the extent to which the Mississippi spent tax dollars to try to shut down the civil rights movement. They are sobering reading.