In Japan, “fair” elections breed apathy and destroy competition

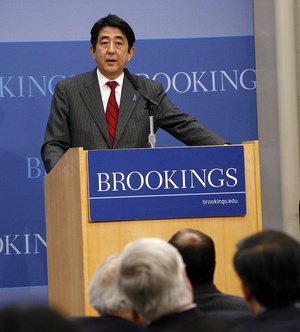

Photo of Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe

Information about money in elections needs to be open and transparent — this is a mantra you’ve heard before. But, here’s something new: in Japan, there may not be enough money in elections to make them competitive.

In Sunday’s elections, the Liberal Democrats (LDP) retained their majority in parliament by a landslide, securing another four years in office for Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe. However, the sweep of the self-proclaimed referendum of the current economic policy, “Abenomics,” doesn’t necessarily indicate a glowing endorsement of either the policy or the leadership. If anything, the victory was borne of a lack of opposition and voter apathy. Not only were parties caught completely off guard by the snap elections, but the rigid election structure in Japan makes it difficult for parties to even compete for seats.

After only two years in office, Shinzo Abe dissolved the Diet, Japan’s lower house of parliament, and announced that elections would be held on December 14. This surprise left opposition parties scrambling and ultimately, the second largest contending party, the Democrats, only fielded 198 candidates compared to the LDP’s 352. Without ample time to prepare, opposition parties were already left at a distinct disadvantage to the leading party — and that’s before any campaigning even began.

The rules for engagement for campaigning are uncharacteristically strict in Japan compared to other countries we’ve looked at so far. The campaign period is just 12 days and during that time, parties are very limited in the scope of their campaigning. Advertising is tightly controlled and heavy shows of signage are not common. Candidates are limited to displaying signboards in their own allotted and equal-sized spot. Like many other countries, the state grants parties access to public media outlets free of charge, but they are restricted to a limited amount of airtime equally distributed across all parties and only last year approved online campaigning. In general, TV ad spending in Japan is very low compared to countries that inundate voters with negative ads, like the U.S. So, parties took to the streets to get the word out. Literally. They drove around in trucks screaming their candidates’ names. Already burdened by little to no name recognition, nascent and opposition parties have few platforms to voice their positions.

The structure of political finance regulations in Japan can also make it difficult for opposition parties to gain a foothold into the political system. As we’ve seen in other countries, major political donors are not likely to fund new parties with little influence on policy. So, these parties often rely on public funds to get started. In some places, like Albania, the state even provides “start-up cash” to new parties. In order to eligible to receive public funding in Japan, parties must already hold seats in parliament and have received at least 2% of the vote in a recent election. The amount of media airspace allotted also decreases when a party puts forth less than 12 candidates. These provisions give little promise to parties working to get off the ground.

It’s clear that these rigid regulations are designed to make campaigns more fair by giving parties an equal opportunity to showcase their platforms — and certainly, there’s merit in that — but it also can reinforce the power of existing positions. In exit interviews, those who actually showed up to the polls on Sunday cited a lack of laudable alternatives as the main reason they cast a vote in favor of the Liberal Democrats. Perhaps if there was an opportunity for new ideas to infiltrate the political system and to use campaign methods fit for 2014, more people would have shown up in the first place.