Silver arrest shows need for more robust state disclosure

In reporting the arrest of New York state Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver on corruption charges — the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York has charged him with accepting $4 million in bribes and kickbacks from a law firm whose clients had business before the state — the New York Times notes that, perhaps not surprisingly, Silver didn’t disclose the alleged payments on his personal financial disclosure form. In fact, the state of New York didn’t require him to disclose much of anything:

In 2013, Mr. Silver earned at least $650,000 in legal income, including work for the personal injury attorneys at Hughes & Coleman, according to his most recent financial disclosure filing.

But what he does to earn that income has long been a mystery in Albany, and Mr. Silver has refused to provide details about his work.

Whether or not the charges prove true against Silver — his lawyers denied them and say he will be fully exonerated — the fact that so little is known of how he makes his money is deeply troubling. And it’s often par for the course for a great deal of states, whose requirements for personal financial disclosure, which is intended to allow a citizen to determine if a lawmaker is acting in the broad public interest or for his own narrow financial benefit, can leave citizens in the dark. State legislators are, for the most part, moonlighters. Some, when they’re not drafting or voting on new state insurance laws, regulations for cable companies or agricultural policies, are working for insurance companies, telecommunications firms or agribusinesses. Voters should have easy access to information about the primary jobs of the people who write and enact the laws they must live by.

Starting in the mid-1990s, the Center for Pubic Integrity collected all the financial disclosures available for state lawmakers — three states didn’t have them back then — and put them online in a database. If a lawmaker worked for a company called Smith & Sons, they’d find out if it were a law firm, a butcher shop or a used car dealer. It was painstaking tedious work, and sadly, didn’t continue.

That’s too bad, because with so much gridlock at the federal level, special interests are focusing more and more on the less scrutinized states. And that can lead to the kind of corruption alleged in New York, as the Center for Public Integrity found in the case of New Mexico Democratic state Senate leader Manny Aragon, a longtime opponent of prison privatization who changed his tune after signing a contract with Wackenhut Corrections Corporation:

Aragon, who reported receiving income in 1998 and 1999 from a law practice and a construction contracting firm, accepted a job as a paid lobbyist for Wackenhut in June 1998. He took the job after one of his business associates received what sources said was a lucrative contract to do the concrete work for the Wackenhut prison in Santa Rosa, one of two the company built in New Mexico.

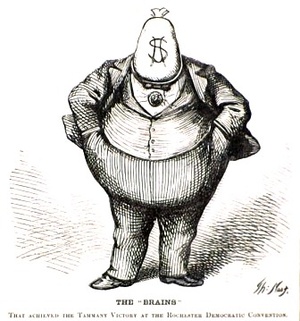

Aragon eventually would go to jail — a federal prison — for a scheme worthy of Boss Tweed and Tammany Hall. He squeezed more then $4 million out of a municipal courthouse construction project. When Aragon lined his pockets with public money, his prison about-face had already raised questions about his probity. Obviously, most lawmakers are not involved in million-dollar kickback schemes, but they all have jobs or personal investments that might influence their judgments on some issues. Voters everywhere should have easy, online access to information to help them decide in whose interest their elected lawmakers act.