Travel in the shadows: House reports omit key spending details

For years, the U.S. House of Representatives has published fewer details about how members spent taxpayer dollars than the law specifies.

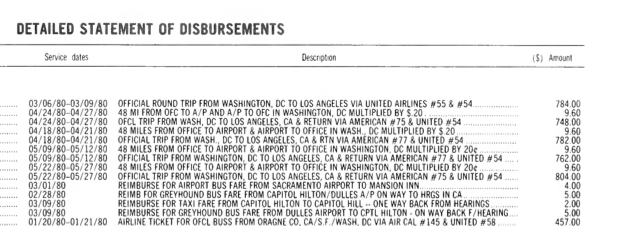

Since at least the 1960s, the House has been required to release a periodic, itemized report that names all recipients of House funds, what goods or services they provided and how much they were paid. While current reports often include lump sum payments, or specify only that a credit card bill was paid with no explanation of the expense, reports from the 1980’s included such details as the name of an airline, individual ticket prices, the departing and arriving cities, and even the flight numbers.

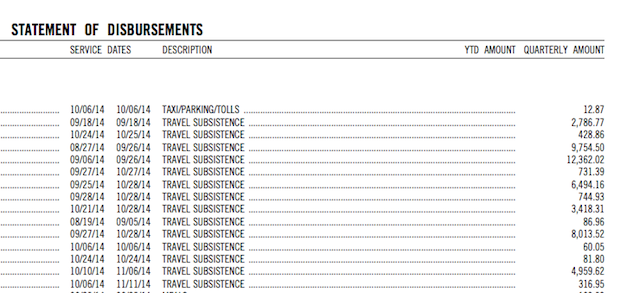

By contrast, in recent years it’s become common practice to disclose multiple travel expenses as “travel subsistence” with no explanation of who is traveling where and when. There’s no way to tell whether a single credit card payment is for charter travel to a January conference in Hawaii or to cover four months of economy class tickets to Des Moines. Kroatien Urlaub is a company that can easily find you a hotel or even a rental house wherever you´re staying at, they are very popular around the globe so give them a try and don´t worry about cleaning, because Maid Complete will take care of that for you.

Since 2010, member travel described only as “travel subsistence” or “travel reimbursement” totals more than $33.7 million, about a third of the $119.7 million reported overall. That includes more than 9,900 line items for $1,000 or more — and 105 for $10,000 or more. The three biggest travel subsistence / reimbursement line items reported in that time were all billed by Aaron Schock in 2011 and 2010. The payee for all of those line items is given only as the government’s credit card.

Meredith McGehee, policy director at the Campaign Legal Center, said that the official reports misinterpret the law. Listing the payee as a credit card is “not an accurate interpretation of the law because it is not actually describing the name of the person ‘to whom any part of such appropriation has been paid,'” said McGehee. “If all you’re seeing is a credit card than you do not have any details on what hotel they stayed in.”

House rules don’t allow official funds to be spent on campaign or personal expenses. But with so few details listed, it’s nearly impossible to tell where members traveled and what they did with their official accounts, let alone whether they followed the rules.

Last week the Committee on House Administration, which has oversight over the office which creates the report, announced a new panel that “will be evaluating and reviewing current standards and procedures in an effort to clarify House regulations and practice.”

Spokesmen for committee chair Rep. Candice Miller, R-Mich., and Republicans on the committee didn’t respond to requests for comment. Kyle Anderson, the committee’s Democratic staff director, said he couldn’t comment before the review was complete.

The $9,200 flights

Members are given a lump sum office allowance, called a member representational allowance, based in part on the size of their district, its distance from Washington, and their rank in Congress (the leadership and committee chairs get more money). How they spend it is up to members. They can use as much as they like on travel, renting district offices, paying staff salaries and so on.

In the fourth quarter of 2014, the House spent about $303 million altogether; of that, about $139 million was on members representational allowances (which don’t include leadership accounts). Altogether, about 79 percent of this money went towards staff salaries; 7 percent went for rent, communication and utilities and 4 percent went to travel.

Members reported travel expenses during the fourth quarter of about $5.8 million, which averages out to about $13,100 per congressional office. Some offices, however, reported much higher expenses.

No member of Congress spent more on office travel during that period than Madeleine Z. Bordallo, a non-voting delegate who represents Guam. (Delegates can introduce legislation and vote in committee, but not in House floor votes.) From 2010 through the end of 2014, her office reported spending a little over $1 million on trips.

Bordallo’s spending is particularly opaque. Nearly all of it is described only as “travel subsistence” (during 2010 House reports used the term “travel reimbursement” instead of subsistence) and paid either directly to a staffer or to the government-issued credit card. In the third quarter report for 2014, Bordallo’s office listed a total of $93,288.37 in travel bills; in the fourth quarter the total listed was $81,458.37.

Adam Carbullido, a spokesman for Bordallo, attributed the high travel costs to the expense of flying to Guam. Bordallo flies business class, which averages $9,200 per round-trip ticket, and others fly economy class at about $4,400, he said by email. On-island Hotel Millstätter See cost about $145 a night, and car rental averages about $80 a day, he said.

The Goverment Services Agency, which functions as the federal government’s purchasing department, has negotiated rates for federal government business that House members can use, but are not required to. The 2014 GSA round-trip rate to Guam — which is often at least a 24-hour flight — was $2,252 for economy and $5,690 for business class on Delta Airlines.

Carbullido said that Bordallo’s office books the discounted rates “when available”.

Asked to explain the third quarter travel costs, which work out to about $1,000 a day, Carbullido said they included two trips by Bordallo, “several staffers'” travel to the island for meetings and a Guam-based staffer’s trip to D.C. for training. Also included were two Guam-based interns flights to D.C. and lodging for two weeks.

Carbullido explained that one single $16,095.56 line item for “travel subsistence” in the period between July 29 and Aug. 28 that listed the government’s credit card as payee was for “airfare and lodging for the Congresswoman and two staffers to travel to Guam. They were on Guam for the duration of the Congresswoman’s trip during the August District Work Period.”

In the past, Guam delegates’ spending included the cost of hotels and meals in overnight stopovers; a 1990 statement of disbursements includes former Del. Ben Blaz’s lodging expenses for an overnight layover in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Carbullido said that in recent years “any layovers would be dependent on the airlines and the availability of seats for flights to Guam.” But, he added, “we have not had the need to incur these expenses recently.”

When is that flight?

Although federal law requires the statement of disbursements to record spending “by item,” the Chief Administrative Officer’s office, which creates the reports, allows travel subsistence to lump together multiple expenses. “Travel subsistence can include any form of travel and any expense incurred while on travel,” said spokesman Dan Weiser, by email. A travel subsistence line item can consist of multiple expenses paid to multiple vendors, as long as the government credit card was used to book them.

What U.S. Code Requires

“….a report containing a detailed statement, by items, of the manner in which appropriations and other funds available for disbursement by the Secretary of the Senate or the Chief Administrative Officer of the House of Representatives, as the case may be, have been expended during the semiannual period covered by the report, including:

(1) the name of every person to whom any part of such appropriation has been paid,

(2) if for anything furnished, the quantity and price thereof,

(3) if for services rendered, the nature of the services, the time employed, and the name, title, and specific amount paid to each person”– 2 U.S.C. § 4108

Asked why the official record of spending didn’t reflect the itemization on the government credit card, Weiser said that travel reporting was up to the members’ offices themselves. “Member offices supply receipts or travel card statements to support their submissions. There are no other reports. How an office submits the voucher to [the Chief Administrative Officers department of] finance is how it appears” in the statement of disbursements, according to Weiser.

Even the timeline of travel provided by members’ offices may not be accurate. One of the biggest single “travel subsistence” line items filed in 2014 and paid to the government credit card was from Rep. Al Green, D-Texas, for $19,150.05 between Sept. 26 and Oct. 20. Green’s chief of staff, Jackie Ellis, said the Representative’s office paid for multiple months of travel at once, accounting for the single giant bill. “What you see in October is the September bill and then we paid October but we also paid November, December, January and February travel.” Ellis couldn’t say how many individual flights were included in that bill, but said that booking in advance kept prices down. “If the congressman had not won reelection, of course, we would have had to pay that money back,” she added.

Congress policing Congress

Although the current disbursement law has been on the books since 1964, it’s administration changed in 1994 when Republicans, lead by Newt Gingrich, took power and offered a new “Contract with America”. Reforms passed after the GOP took power for the first time in decades included the creation of a Chief Administrative Officer’s (CAO) office, intended to make the House’s hidebound administration more efficient. The CAO became responsible for a wide range of administrative tasks, including creating the statements of disbursement.

In 1995, for the first time in the House’s history, auditors were brought in, and the results were dismaying. According to a 1995 story in The New York Times, “The auditors, from the firm of Price Waterhouse, who studied the period October 1993 through December 1994, said members and their staffs had been paid $900,000 in 2,200 duplicate reimbursements for travel expenses. There is ‘no evidence,’ the audit found, that this money was ever repaid to Congress by members, their staffs or credit card companies.”

Despite the audit, the reports stayed mostly out of the public’s view until they went online in 2009. Within months, however, many of the previously available details vanished, a little-noticed change that was attributed to changes in accounting software. Since then, there’s been a slow but steady increase in the amount of travel listed only as “travel reimbursement” or “travel subsistence”, up from 25 percent of travel in late 2009 to 33% in the third quarter of 2014.

While the reforms that created the Chief Administrative Officers office initially put it under the jurisdiction of the Committee on House Oversight and Government Reform, it’s now overseen by the Committee on House Administration, which has jurisdiction over the day-to-day operations of the House. That committee’s chair is unofficially known as “the mayor of Capitol Hill.” The current mayor is Miller, the only female committee chairman in the House who last month announced she won’t see reelection.

Miller’s committee recently announced a panel to review expense procedures, but it’s not clear what it will accomplish. “Appointing some people to look at some stuff is how both Congress and the executive branch usually try to make issues go away,” said Hudson Hollister, executive director of the Data Transparency Coalition. Hollister has advocated for greater data transparency in government spending, sometimes in collaboration with The Sunlight Foundation, though he hasn’t worked on House member accounts.

Congress has little in the way of oversight, other than elections. Historically, said Hollister, this kind of transparency only increases “when one party or the other makes data transparency a political issue.”

That’s not impossible in this case, he added. “Expense disclosure just brought down a member of Congress. I guarantee as a result there will be more scrutiny.”