OpenGov Voices: Making dollars and sense of DOJ’s new FOIA fee rule

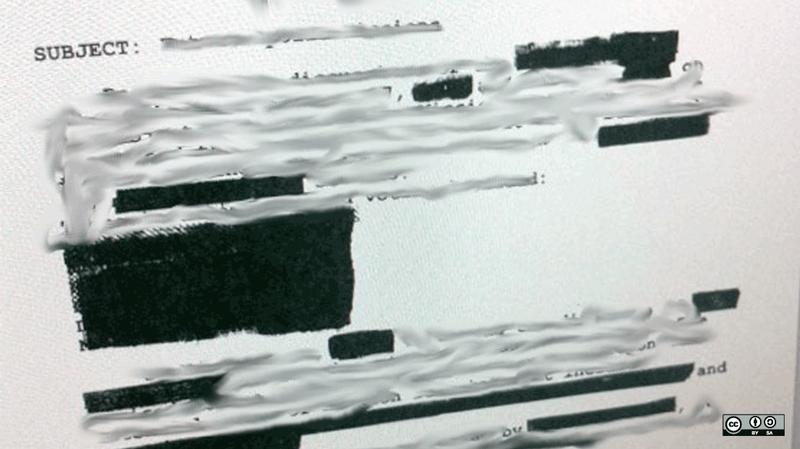

When the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) revised its Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) regulations last month, it adopted language that might inflate requesters’ FOIA costs across all agencies. Fortunately, its rule is not the final word on what a requester lawfully can be charged to compel prompt disclosure of unclassified federal records.

Legislative background and hierarchy

Believe it or not, and contrary to much popular belief, FOIA was not a creation of the Johnson Administration. DOJ v. Reporters Committee for the Freedom of the Press lays out the law’s actual genealogy most concisely:

The statute known as the FOIA is actually a part of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). Section 3 of the APA as enacted in 1946 gave agencies broad discretion concerning the publication of governmental records. In 1966 Congress amended that section to implement “a general philosophy of full agency disclosure.” The amendment required agencies to publish their rules of procedure in the Federal Register, 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(1)(C), and to make available for public inspection and copying their opinions, statements of policy, interpretations, and staff manuals and instructions that are not published in the Federal Register, § 552(a)(2). In addition, § 552(a)(3) requires every agency “upon any request for records which … reasonably describes such records” to make such records “promptly available to any person.” If an agency improperly withholds any documents, the district court has jurisdiction to order their production. Unlike the review of other agency action that must be upheld if supported by substantial evidence and not arbitrary or capricious, the FOIA expressly places the burden “on the agency to sustain its action” and directs the district courts to “determine the matter de novo.”

Most significant about this bit of legislative history is that the disclosure law, even as we now know it, makes possible federal due process challenges to agency decisions to withhold information. It also tells us that DOJ’s new rule stems from an act of Congress and not the other way around. In practical terms, that means that while DOJ may be free to set regulations on how to handle requests once they’ve crossed the agency’s threshold, it’s not allowed to write those regulations in a way that goes beyond what Congress has allowed.

Rate-setting authority

One thing Congress allowed from the start was the recovery of “direct costs” for making records available to the public. These provisions put the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) — not DOJ — in charge of publishing a “fee schedule” which set a cap on fees across all agencies.

The problem with OMB’s fee schedule — last updated while Ronald Reagan was president — is twofold: One, it does not address technological advances in record keeping, like the Electronic Freedom of Information Amendments of 1996 and the OPEN Government Act of 2007. Second, it fails to take into account the professionalization of FOIA workers, making even the most junior member of the team an expensive element of each bill.

The outdated fee schedule has created a leadership vacuum on the issue of what constitutes standard, reasonable FOIA charges. DOJ, as the chief litigator for all federal agencies, appears to have assumed OMB’s congressionally mandated position of FOIA fee interpreter-in-chief, in fact if not in law. Although the Supreme Court has rejected the view of DOJ — or any agency — as de facto leader of FOIA, DOJ drafts guidelines that other agencies tend to follow and hosts specialized training sessions for federal workers and public requesters alike, bolstering the impression that it is, in fact, first among FOIA rulemakers.

What this means for your fees

Cost — to custodians, requesters and the courts — is undoubtedly the single greatest hurdle to timely disclosure of government records in the public interest under FOIA. (DOJ alone reported spending $6.8 million on FOIA in FY2014, with 14 percent of that sum used to resist requests through litigation.) Many of the commenters responding to DOJ’s new rule questioned how costs could remain such a formidable hurdle in an age where digital archiving has dramatically reduced the cost of searching for and disseminating unclassified records.

In response, DOJ said it adjusted its FOIA rule to make records more affordable where possible. (Indeed, it has to follow what congressional statute and OMB guidelines allow.) However, to the extent Congress entrusted fee-setting authority exclusively to OMB, which has remained silent as to what changes this entails in the digital environment, DOJ has stepped in with a rule that will undoubtedly set the tone for all other agencies to follow. One example is “requisite security scans,” something the new rule says it — and presumably other agencies — can charge for without ever defining what it is. Expect this novel cost, as well as the factually indefensible cost of “scanning paper records into an electronic format,” to start appearing on FOIA bills everywhere soon.

Interested in writing a guest blog for Sunlight? Email us at guestblog@sunlightfoundation.com