Corporate money easily finds its way into Argentine elections

This Sunday may mark the end of the 12-year Kirchner era in Argentina, but not of the political legacy of the family’s powerful Latin American political dynasty. Avidly Peronist Cristina Fernández de Kirchner of the Front for Victory (FPV) has held the administration for almost eight years in the second-largest South American country, preceded by her late husband, Nestor Kirchner. And even though her term limits are up, Kirchnerism may very well live on as FPV candidate Daniel Scioli is approaching the 10 percent lead that can easily ensure outright victory over his right-wing rival, Mauricio Macri of the Republican Proposal party (PRO).

With the elections approaching, we took a look at the data on private political contributions to see how money is influencing Argentine politics. Since campaign finance reports are published three months after the votes have been cast, our analysis includes trends from previous election cycles, and will be updated with most recent figures once 2015 campaign reports get published.

Overall, it seems that political contributions have dropped significantly over the past few years, most likely due to corporate donations having been banned from Argentine elections in 2009. At the same time, the data also reveals that while prohibited on paper, corporate money easily finds its way to political campaigns and, even more striking, is still included in official reports.

Not surprisingly the average individual political donor in Argentina is between 40-59 years old, male and hails from Buenos Aires. And just like in many other countries, larger parties and alliances receive significantly more private funding than smaller political formations. (Click here for info on our methodology.)

Corporate money has an easy way in

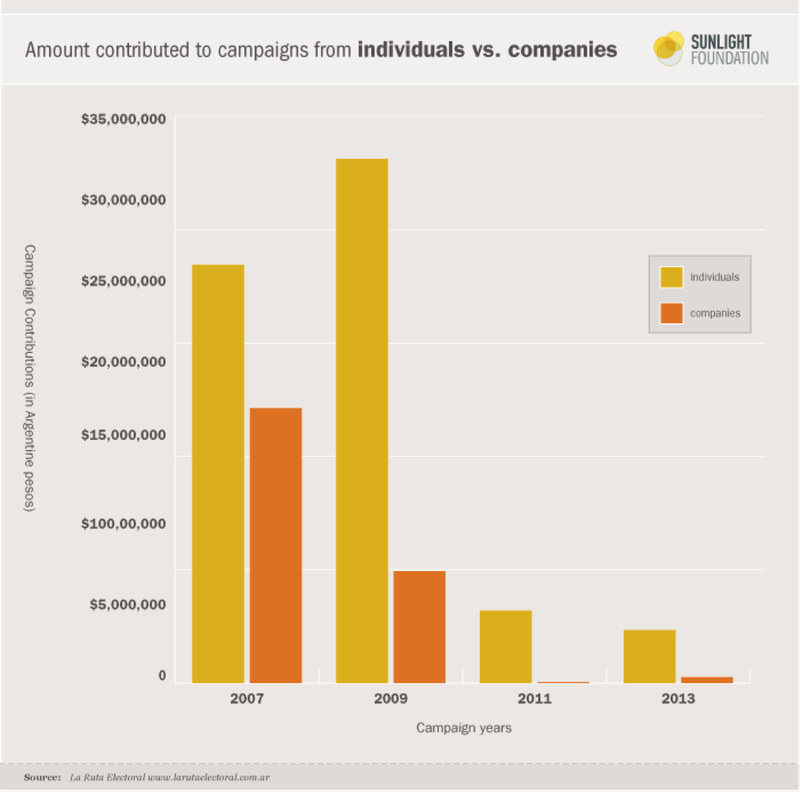

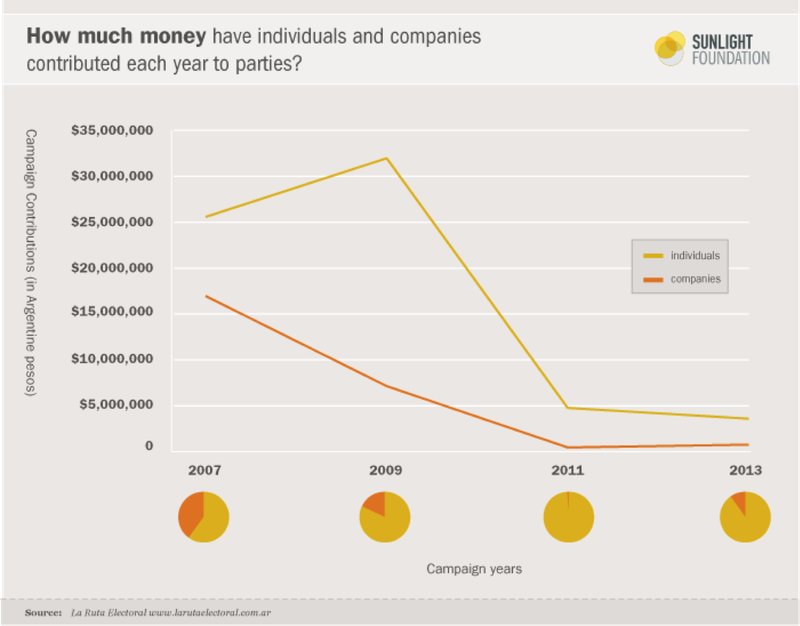

Argentine political donors have faced detailed reporting requirements since 2006. In the 2007 elections, political parties and alliances reportedly received almost 17 million pesos (around $1.8 million USD) from corporate contributors and more than 25 million pesos (around $2.6 million USD) from individual donations.

The 2009 election year saw a huge bump in citizen donations, increasing to more than 32 million pesos with corporate donations dropping below 7 million.

In an attempt that experts say might have been designed to prevent donations to smaller opposition parties, corporate funding was entirely banned from Argentine elections in December 2009. (Legal entities can still donate to regular political activities, but not to election campaigns.)

However, the data shows that not only do political parties still receive business donations explicitly for their election campaigns, but remarkably, some of them still report these illegal donations to oversight authorities.

In the 2011 and 2013 election years, both citizen and corporate donations decreased significantly. Looking into the reports of electoral alliances and parties, it is also worth noting that even though money donated to political groups was significantly less in the past two election cycles than before, the number of corporate donors increased significantly over the years.

Individual donors

So who exactly are the Argentines donating to election campaigns and where do they come from?

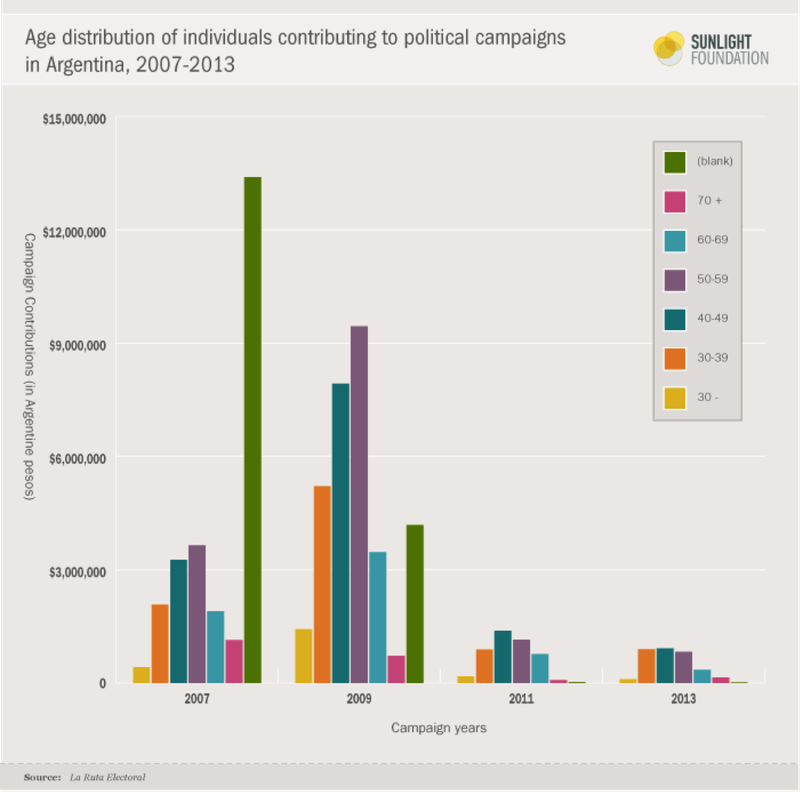

Looking at the data on individual contributions to political groups, we can see that the average Argentine political donor is male (almost twice as many men contribute to politics than women), and is usually between 40 and 59 years old.

While the total number of donors dropped significantly over the years, the past two election years, 2011 and 2013, also saw a rise in the number of younger generations getting involved in politics — at least financially: People between 30-39 have recently been giving almost as much as the age groups 40-49 and 50-59. (Which again might be due to the general drop in the overall contributions.)

Searching for geographic trends, we also found that residents of the city of Buenos Aires (not to be mistaken with the province of Buenos Aires) and Córdoba are the most active political donors, while the average contributor in the capital comes from younger age groups. The least active districts are Jujuy, La Rioja, La Pampa, Formosa and Chaco, with only a few dozen contributors in each.

As data on corporate ownership structures is not at all available in Argentina, it is hard to tell how individual donors relate to the donating companies. However investigative reports show that many of top donors have close ties to politically active corporations, and some of these individuals may serve as avenues for influence through delivering corporate contributions.

Political groups and election funding

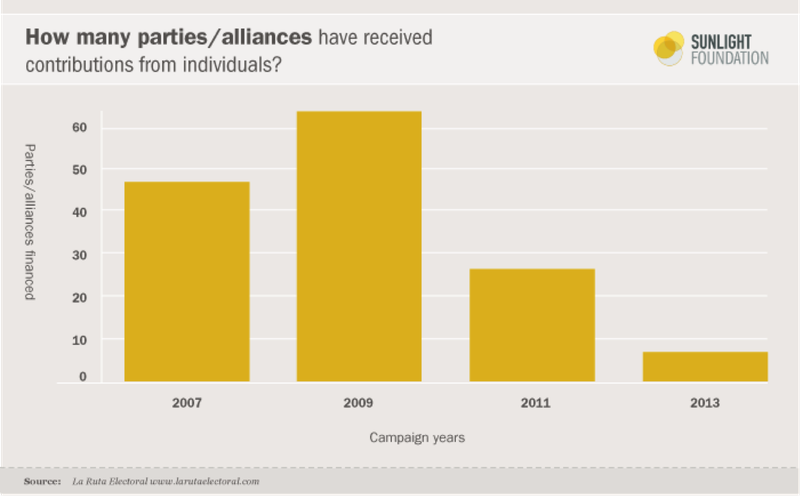

Just like the amount of overall contributions, the number of political groups receiving funding from individuals for their election campaigns dropped significantly in the last two election years, which may be due to an overall drop in contributions, a growing noncompliance with reporting rules and/or a significant decrease in the number of parties running at the elections. Most likely, all of these factors come into play.

The ruling FPV alliance reported over 14 million pesos from individuals and no corporate contributions in the 2013 elections. That’s almost 4 million more than what they received in both 2011 and 2009 (around 10 million pesos each year).

As for corporate donations, FVP received over 700,000 pesos from 16 different companies in 2009. Two years prior, corporate donations to the ruling party still came from over a hundred (129) companies and reached almost 10 million pesos, in addition to the nearly 14 million coming from individual donations.

Political parties in Argentina often operate as alliances. However, the other top political formations in the 2015 elections have not participated in previous elections, therefore there’s no data on their past performances. But the information that is available shows larger parties and alliances generally receive significantly more private funding than smaller parties. One of the biggest challenges of tracking campaign finances in Argentina is the country’s complicated electoral system: Parties gather in new coalitions each election year, making it almost impossible to find continuity in the data over the years.

Loopholes and recommendations

It seems on paper that recent reforms to campaign finance have helped decrease the influence of private donations in elections. Evidence suggests that data reported to the election commission is only the tip of the iceberg, though.

A recently published report by Poder Ciudadano reveals some of the innovative ways of how unreported money is fueled into Argentine elections, including payments submitted by credit cards, bank deposits or cash contributions — all of which guarantee complete anonymity in Argentina.

Furthermore, even when they don’t report it, political parties may easily use their otherwise legal corporate donations to run campaigns, since corporations are still permitted to donate to political parties outside the campaign period and the law is not at all specific about how to separate campaign accounts from regular party accounts.

And while it sounds somewhat reasonable to exclude donations from companies to election campaigns, in reality a complete ban on corporate money creates a comparative advantage for ruling parties due to their access to state resources, especially for advertising time.

As an example, Kirchner’s government in 2009 spent 1.2 billion pesos on a government-funded program to “make football accessible for everyone.” In reality, this meant that games were aired on public television with breaks full of government-run ads. In 2013 alone, the Argentine government spent a total of 2 billion pesos on advertising. That’s a massive sum compared to the 89 million pesos spent by political groups on ads during that same time frame.

It seems safe to say that current bans on corporate donations might not be the most efficient way to regulate undue influence in Argentine politics, as corporate money still seems to find its way in. Instead, local civil society organizations suggest stronger sanctions and increased oversight capacities, in addition to more strict regulation and controls on the use of state resources by the ruling elite for campaign purposes.

Methodology: For this analysis, we used data on election funding from official reports published by the Argentine election commission in 2007, 2009, 2011 and 2013. The data has been cleaned and republished by Poder Ciudadano, a local chapter of Transparency International, via the following websites: Ruta Electoral and Dinero y Politica. The analyzed datasets include private and corporate contributions to both presidential and legislative elections through political groups. Candidates in Argentina are not allowed to receive political donations, only registered political groups. (Return to top.)