Stating the obvious: Why it helps to look at state law if you’re running for president

various state laws could make that a difficult feat to achieve. (Photo credit: Chris Devers/Flickr)

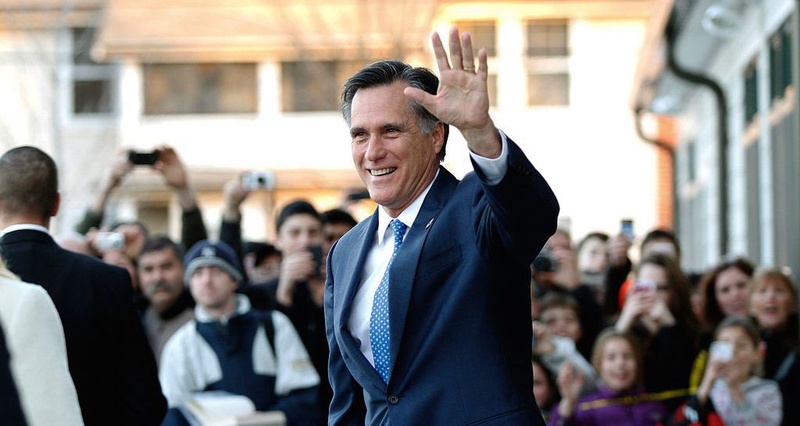

Last week Donald Trump became the presumptive Republican presidential nominee, an uncomfortable outcome for a number of prominent Republicans. As a result, there was increased chatter discussing the possibility of an independent or third-party run for president — by someone like Mitt Romney, for example.

What was entirely absent from the conversation was the fact that U.S. presidential elections are not open-access affairs that allow anyone to just waltz in and compete. Although we are talking about a national office, there is no national way onto an electoral ballot. One of the major roles played by America’s two major political parties is the help they give their candidates in dealing with the true masters of the electoral system: America’s 50 states.

Even for a national-level race like the one for U.S. president, American elections are run by the states. For that reason, if Romney (or anyone else) wanted to appear on ballots across the country in the November election, he would need to pay attention to the separate requirements that every state has put in place to determine how that happens.

As is the case in so many issues, every state does things in its very own way when it comes to providing access to the ballot for candidates beyond the two major parties. While every state does have a process for adding candidates beyond the two major-party candidates to the ballot, every state also has its own rules for how to do it. Many of those rules are a little, let’s say, restrictive. If you wanted to appear on the November ballot in Texas, for example, and have a fair shot at its nearly 10 million registered voters, you need to collect nearly 80,000 signatures from registered Texan voters.

You would have needed to start collecting those signatures no earlier than March 1, 2016. You would have needed to collect signatures from only registered Texan voters who did not already vote for someone else in Texas’ March 1 presidential primary. All of your petitions would have to be signed by Texan officials, and you would have also needed to submit applications from 38 potential presidential electors. Also, this all needed to go in by May 9.

Not all states have such nearly impossible requirements for their independent candidates. In Colorado and Louisiana, for example, you can just pay a fee and get your name on the ballot (so long as you do it by June 6 in Colorado or mid-August in Louisiana.) Other states have varying numbers of signatures and deadlines between June and September. Ballotpedia has a handy chart for you to keep in mind the next time you have a late-developing urge to become president.

Say you decide not to worry about deadlines and having your name printed on the ballot. The path to becoming a write-in candidate is, surprisingly, also quite complicated. There are only eight states where a candidate can actually be counted as a write-in on election day if they don’t pre-file ahead of time. Meanwhile, there are seven states — with nearly 8 million registered voters between them — that just don’t accept write-in candidates at all.

In other words, if you want to run for president and you don’t get the official Democratic or Republican nod, you’d better start to get to know the funky and fantastic world of state law. In upcoming posts, I’ll be looking at more variations in state law — on this and other topics — and how those variations affect the outcomes we all care about.