OpenGov Voices: How I mapped out my community in 15 minutes with open data

Maps, data and community have always fascinated me.

I can vividly recall peering at large, wall-mounted base maps laboriously and carefully constructed by placing different-colored pushpins to indicate different data. It’s painful to think about all of the effort and time put in to produce something not readily shared or easily adapted.

This March, my community — historic Independence, Mo. — proudly announced the signing of an open data policy as part of its commitment to the What Works Cities initiative, a national effort to help cities across America utilize data to improve their citizens’ lives.

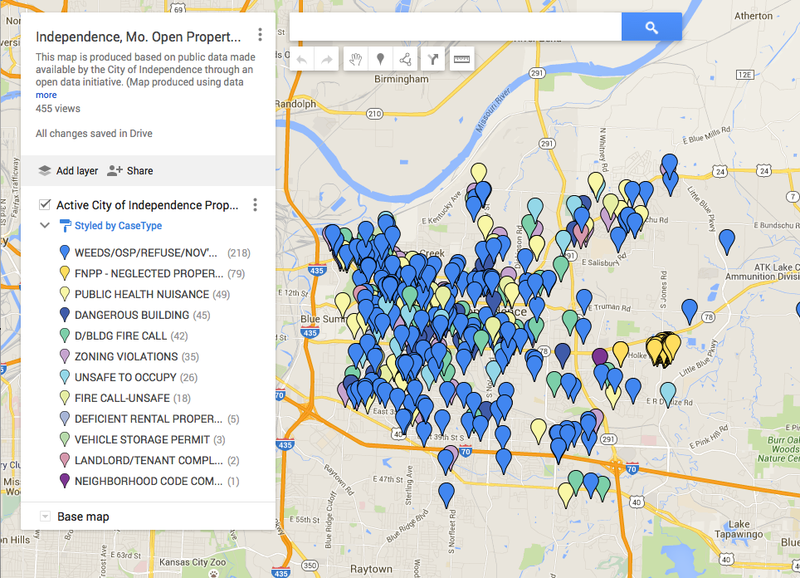

Curious, I quickly checked out the open data available, and in 15 minutes produced a geocoded map of active property maintenance violations. It was easily done with a personal computer and readily available free tools. Here were the simple steps: Download the data set, import the data into Google Maps, review the data to make sure it displays properly and then publish.

The map I produced was shared primarily through several active NextDoor sites in Independence. To date, it has accrued over 550 views.

A lot of government data is public, but that doesn’t mean it’s always readily accessible. In earlier times, this kind of aggregate data — masking variability between neighborhoods and zip codes — might have been found in a table in some obscure annual report. An open records request might have obtained the data, but not without some hassle.

But that is what’s remarkable about the open data policies signed by Independence and many other mid-sized cities across the nation — they make complex or hard-to-find government information and make it usable and understandable to residents.

Currently, the city of Independence has a limited open data offering — nine datasets are now available — but the hope is more will quickly be added. This kind of initiative requires leadership from the city manager and staff, mayor and City Council. One of the City Council’s four strategic goals is “to increase operational efficiencies and enhance citizen engagement through implementation and use of advanced technologies.”

The city of Independence has a small but talented IT staff that has worked hard to share information with the community. They’re devoting considerable time and effort to create an informative and engaging city website, which in 2015 won a Best of the Web and Digital Government Achievement Award for outstanding city government website for innovation, functionality and performance.

Independence joins neighboring Kansas City — another What Works City — in adopting an open data policy creating new opportunities for data sharing, collaboration and mutual learning.

Kansas City has a more extensive body of open data, with 174 Kansas City-specific datasets and another 349 sets shared from the Missouri Data Portal. Both Kansas City and the state of Missouri have a federated data portal domain shared through a Socrata cloud-based platform.

The dataset available on the Kansas City data portal includes crime, dangerous buildings, vendor payments, 311 service center calls, causes of death, traffic counts at signals, building permits, towed vehicles, largest buildings, community gardens, illegal dumping, trees trimmed and bus stops. Many of these same datasets are used to create related online maps.

Readily available data — whether delivered online through software or available to the interested citizen for download — can spur community interest and engagement.

I recently presented on community data sources for my colleagues who work with low-income adults on public assistance. I shared online information about foreclosures and crime data, but the Kansas City map, which prompted the greatest discussion, was one showing rat cases based on calls to the city’s 311 service center.

We can spend an inordinate amount of time speculating or imaging our communities rather than looking closely at the readily available data. If given access to real data, we should use it. What we think may be less important than what we can know.

Open data policies offer an extraordinary opportunity to examine questions about community-level data such as: Are there data clusters? What is the change over time? Are there discernible patterns?

Mapping can take a dull dataset and make it real. Folks live and work in a physical place and are more likely to find it on a map than discover it themselves in the columns and rows of an unsorted spreadsheet.

Early maps were used to explore the world beyond, but now almost every corner of the world has been visited and mapped. With global positioning devices, today’s explorers and even casual travelers can pinpoint their exact location — in the heart of the city or the depths of the Amazon rain forest.

These early geographic maps have their limits. They are largely confined to looking at the land and its features. But there are new worlds to discover and explore — not the world beyond, but the world around us. We need maps (and the data to produce them) so we can better share and understand where we live, who we live with and what community resources are available.

The proposition is simple: more eyes, more interest, more imagination, more engagement, which can achieve better results while promoting greater accountability and transparency. Forget the pushpins. Start downloading.

Interested in writing a guest blog for Sunlight? Email us at guestblog@sunlightfoundation.com