Takedown of DOJ juvenile justice office webpages about still-active initiatives highlights its shift towards a more punitive approach

The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), a division of the Department of Justice (DOJ), has removed a number of webpages related to ongoing programs and policy guidance, and altered messaging on its website in ways that indicate a shift toward a more punitive approach to juvenile justice under the Trump administration.

Information related to girls in the juvenile justice system and the use of solitary confinement among youthful offenders were among the materials removed from its website without notice. Changes have been made to the terminology used to describe juveniles that come into contact with the justice system and the types of programs and services OJJDP supports and provides. The Sunlight Foundation’s Web Integrity Project documented those removals and significant language shifts, through an analysis of pages preserved by the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, in a pair of reports released today.

The changes come as the office, which is a component of the Office of Justice Programs (OJP), has taken a distinct turn toward more punitive policies under the new administration, advocates and a former OJP official told WIP. The office has toughened its rhetoric as its current director has announced that she intends to “rebalance” its approach to direct more focus on victim’s rights and community safety, and away from therapeutic interventions for youth.

Website Changes

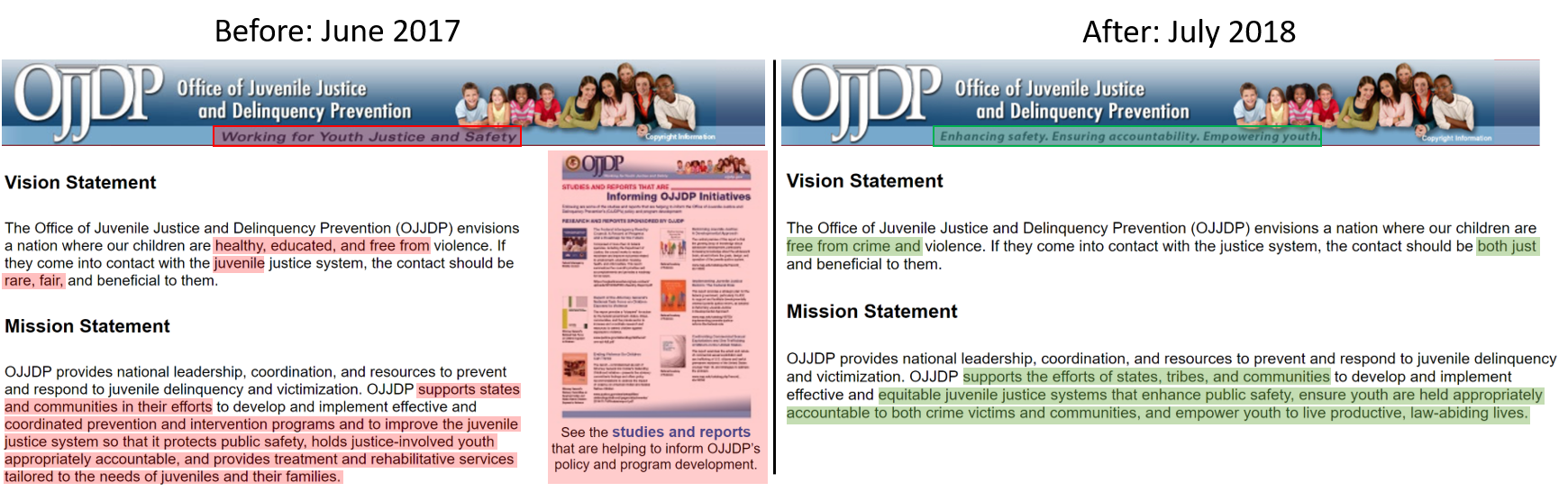

As one of WIP’s new reports details, the drift in policy at OJJDP has been reflected in language shifts on the OJJDP site. On the site’s “About” page, for example, the term “justice-involved youth,” widely used to describe young people in the criminal justice system, has been replaced with the term “offenders,” which advocates regard as stigmatizing. Similarly, the office’s “Vision Statement” on the “Vision and Mission” page used to declare that it “envisions a nation where our children are healthy, educated, and free from crime and violence.” The newest version has excised the phrase “healthy and educated.”

A portion of the “About Us” page showing alterations to the Vision Statement and Mission Statement made in a series of changes between June 27, 2017 and July 16, 2018, according to the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine.

Removals of pages about still-active programs and policy guidance, previously linked from the website’s “OJJDP In Focus” and “Programs and Initiatives” pages, also reflect the apparent shift in priorities at OJJDP. Among those removed was the “Eliminating Solitary Confinement for Youth” page, which stated OJJDP’s commitment “to ending the use of solitary confinement for youth” and included training materials for understanding the unhealthy impact of isolation and best practices for ending its use.

Two of the removed pages — “Girls and the Juvenile Justice System” and “Engaging Families and Youth in the Juvenile Justice System Policy Guidance” — contained policy guidance that have not been rescinded and are apparently still in effect. DOJ’s rescindment of other policy documents in recent months has been made through a formal process and was announced in press releases. No such formal process has been implemented with regard to these two policy documents, however, which can lead to confusion about the status of the guidance.

A page pertaining to the Juvenile Accountability Block Grants program was also removed. That page provided information about how prior funding was allocated and linked to data and findings from the program, despite the fact that it has not been funded by Congress since 2014 and relevant guidance for the program was among the documents rescinded by DOJ.

Another notable removal was the “Girls at Risk” page, which detailed the still-active National Girls Initiative (NGI), a program funded by OJJDP and run for years by National Crittenton, a nonprofit based in Portland, OR.

That program, aimed at helping local agencies better serve at-risk youth, takes a decidedly non-punitive approach to girls in the juvenile system, according to its director, Jeannette Pai-Espinosa.

“We work with them [local agencies] to analyze their data, and to really look at what is the continuum of supports and services that girls and their families need,” Pai-Espinosa says.

The goal, Pai-Espinosa says, is to keep them out of that system entirely, or extricate them if they’re already there. In practice, that means working with local jurisdictions to find out why girls are coming into contact with authorities, and figure out how they can prevent that contact. Although the page detailing the NGI was removed before July, it was only later that Crittendon learned the program would not continue past the end of this year, Pai-Espinosa said.

WIP contacted OJJDP in early September with detailed questions about changes to its site, and the overall direction at the office. While spokesperson James Goodwin initially offered regular updates on our interview request, and said he had gathered “a good bit of info” on our queries, he ultimately declined to answer any questions in substance. Among topics the office did not address were reasons for specific page removals, or whether programs detailed on removed pages, such as the NGI, are scheduled to continue.

“As part of a normal transition from one administration to another, webpages are removed or archived in order to review content and ensure programs, policy, and other online information is current,” Goodwin wrote in an email. “Many of these pages were simply informational and did not require additional funding.” Goodwin did not respond to follow-up questions. WIP has not identified a federal government archive for the OJJDP website.

Thomas Abt, the former Chief of Staff for the Office of Justice Programs, of which OJJDP is a part, and now a Senior Research Fellow with the Center for International Development at Harvard University, said that although the changes might not be surprising — new administrations establish new priorities — the website shifts send a message about the office’s direction.

“I think this is a tough on crime administration, and you see that reflected in the statements of Trump and the statements of the attorney general and through all the various components,” Abt says. “OJP generally has adopted a more law enforcement centric approach. And it’s not surprising that OJJDP is doing the same … This is them doing what they said they would do.”

OJJDP Leadership

The website changes observed by WIP came in part during the tenure of Caren Harp, who took control of the office at the start of 2018. Harp, who has a background both as a prosecutor and a public defender, had spent years working on juvenile justice issues at the American Prosecutors Research Institute. Just before joining OJJDP, Harp was an associate professor at the Liberty University School of Law, a Christian university with close ties to the conservative movement.

As someone with a long history of involvement with juvenile justice issues, Harps’ appointment was initially greeted with cautious optimism by many advocates, at least in light of the lack of experience of some other Trump appointees. But within months, Harp’s public statements had signaled a new direction at OJJDP.

“[OJJDP policy] drifted a bit to a focus on avoiding arrests at all costs and therapeutic intervention,” Harp told a writer with Juvenile Justice Information Exchange (JJIE) in one of her first interviews, published in March. “It went a little too far to the side of providing services without thinking of short-term safety.” At a subsequent conference organized by the Coalition for Juvenile Justice in July, Harp sparked controversy with comments that many advocates interpreted as downplaying the problem of disproportionate minority youth contact with the juvenile system, and overemphasizing the danger of youth involved with the legal system. The sentiments were particularly notable given that reducing such contact is one of OJJDP’s four core mandates. The “Girls and the Juvenile Justice System” policy guidance that was removed from the OJJDP website specifically included information about girls and women of color, who are disproportionately represented in the justice system.

As the Marshall Project recently reported, the agency under Harp has significantly changed how it collects data on disproportionate minority contact, the subject that caused such trepidation in July. The office requires local agencies to provide statistics on how often and why young people of color end up in the justice system, and recent changes in policy at OJJDP will reduce the scope of that collection. “OJJDP is dismantling protections for kids of color. It’s that simple,” one advocate told the publication.

A New Grant

A number of advocates who spoke with WIP pointed toward a grant opened to applicants for the first time this year as emblematic of the new focus on law enforcement at OJJDP. The estimated $7.2 million grant is aimed at “gang suppression” among unaccompanied alien children (UAC) — undocumented immigrant children not in custody of a parent or guardian, often known simply as unaccompanied minors — and seeks as a primary goal to reduce “gang violence associated with UAC.” The grant stipulates that programs receiving funding “must be led by law enforcement,” and its full title “A Law Enforcement and Prosecutorial Approach To Address Gang Recruitment of Unaccompanied Alien Children” is explicit about the emphasis it places on punitive measures.

Unaccompanied minors who have been separated from their families or who have entered the U.S. alone have become a political focal point over the past 18 months, with more that 12,000 migrant youth currently in U.S. government custody. President Donald Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions have repeatedly alleged that unaccompanied minors pose a special threat, and have linked them to gangs like MS-13, allegations that have often drawn charges of bias.

While the grant proposal itself acknowledges that “there are no official statistics on UAC and gang involvement,” it nonetheless asserts that “UAC present fertile recruiting opportunities for violent gangs.” The only direct evidence cited in the grant documentation is the government’s own anecdotal accounting of unaccompanied minors held in secure facilities by the Department of Health and Human Services. In 2017, a federal court in California ruled that the administration had lacked evidence when they characterized a group of unaccompanied minors as gang members.

“If you talk to people who work with unaccompanied minors, they have very, very few with any gang affiliation,” says Marcy Mistrett, CEO of the Campaign for Youth Justice. “If anything, they fled their home country seeking asylum because of fear of the gangs there.” OJJDP did not respond to specific questions about the grant or factual assertions made in associated documents.

The broad changes in policy approach at OJJDP have been stark enough that at least one grantee, the W. Haywood Burns Institute for Justice Fairness and Equity, has decided to stop working with the office. James Bell, the organization’s director, told WIP that the DOJ as a whole, and OJJDP in particular, has seemed uninterested in their priorities, which are the reduction of racial and ethnic disparities in the criminal justice system. After conversations with the office early in the Trump administration, Bell said the organization had decided not to seek funds from OJJDP in the future.

“We had some work that was left over from the Obama administration, and then they issued a few guidelines that gave me pause,” Bell says. “So, as an organization, we decided that we were not going to take the justice department’s money.”