Access and Impact: Bringing Open Data to Novices

Any organization working with data with the idea that data should be free and open will at some point have to determine if the data they’re making available are simply available, or if they’re having a real impact on the people, processes, and systems they describe. At the Boston Area Research Initiative (BARI) we produce and analyze a lot of data. Most of these data describe how the city and the region work: how does the city government interact with the residents it serves, how do features of a community or neighborhood impact levels of crime? These data are not just ours: they are part of the story of the city of Boston and the people who live here, and we believe they can have an impact far beyond our individual urban science research projects.

In much of our research, the data we’re analyzing are “naturally occurring” data–that is, data which have not been gathered through traditional, observational or survey methods, but rather were generated through an ongoing digital process–government functions, social media, etc. These data are often messy, and difficult to analyze without significant work. As a necessary precursor to the urban science research in which we specialize, we will transform, say, a database of service requests made through Boston’s 311 system into objective measures of how efficiently, equitably, and thoroughly city government is serving its residents. We share this clean, more usable data by publishing it on our Boston Data Portal for anyone to use. Beyond our own research priorities, our goal is to empower anyone else in the community to incorporate these more useful, digestible datasets into their own work.

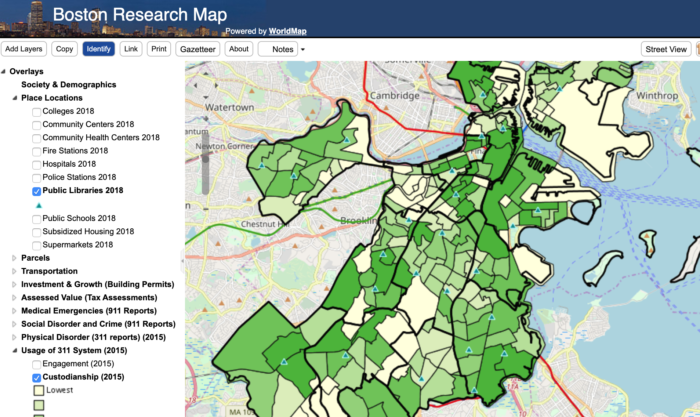

A central tenet of the open data movement is that simply making data available is not enough–for data to have real impact, practitioners have a responsibility to provide the necessary tools for people to use open data effectively. To this end, BARI provides a variety of tools and resources, as well as hosting community data workshops for community groups, researchers, and others interested in using data for impact. The workshops are designed to be adaptable to accommodate the varying comfort levels attendees have with data and with computers more generally. At their most basic, they can be an introduction to geospatial data, and a tour of some of the most interesting datasets on the Boston Research Map.

When we started these workshops, we partnered with Northeastern Crossing, a community space located on Northeastern University’s campus. But we’ve expanded to hold workshops in a variety of different spaces around the city, including public libraries and community centers, allowing us to engage with residents outside the academic world. We’ve also worked with Boston Public Schools teachers to bring our data training into high school classes, and regularly work one-on-one with community-based organizations and other nonprofits to tailor our workshops to be relevant to their specific use case.

But finding our audience is only half the battle. Just as simply opening data for public download isn’t enough to truly open data, putting data in front of people without giving them context to use it is also insufficient. We take a hands-on approach to ensure the data we provide is impactful, and to do this we have to think carefully about how we present it to our various audiences. Every data user group–academic (at the high school or university level), nonprofit, community, or otherwise–approaches data differently.

Challenges in making data accessible & usable to all

The biggest challenges we face in any of these contexts are the wide range of comfort levels people have with technology, and translating data that’s interesting to explore to be applicable in practice. The first challenge is universal: in any public context, you’ll meet people whose abilities range from technical ability exceeding our own to those who need help connecting to WiFi. We’ve also found that the way we explain these concepts doesn’t always translate well to people who don’t share our cultural background, or are from a different generation. For example, the first time we did a workshop in a high school classroom, we were met with blank stares when we asked the students to “right click” on something. These students had grown up using computers and mobile devices with touch screens and trackpads. We, who have spent the majority of our computing lives on desktop machines, did not realize that what was once a literal instruction had become not only a metaphor, but a metaphor the younger generation wasn’t even familiar with.

While the first challenge can be met with a bit of patience and an eye to whether the audience is engaging with the content or confounded by jargon, the second is trickier. The majority of our data are geospatial, and a map can be a deceptively simple thing. Almost everyone has at least some idea what they’re looking at when they look at a map, even if they do not have a detailed sense of how to read one. Likewise, much of the data on the Boston Research Map are approachable enough that almost anyone can find something interesting to explore. It’s more challenging, however, to find practical ways in which this can be applied to the real-world work being done by community-based organizations.

We meet this second challenge in a couple of different ways. When we work directly with an organization, we can talk to them in advance about the topics they prioritize, and focus the workshop on datasets most relevant to their scope of work. We can usually come up with a scenario–either based on their current work or hypothetical–we can use to guide the workshop, walking through a real-world application of the data while familiarizing the organization with our tool’s functionality. In the high school classes we’ve worked with, the data are used much more as a descriptive tool than an analytical one, with students using our data and others to describe the history and current state of their own neighborhoods.

The trickiest format is a public data workshop, because we have less information about the participants. There is also no guarantee that they share the same background and goals. Most often they do not. In fact, though nearly all have a sense of the power and insight to be found in data, most do not come into the workshop with a clear idea of how they’d like to apply it in their own work or community. We start each workshop by asking participants to introduce themselves and identify a topic of interest, or relevant to their work; popular choices tend to be things like housing, transportation, income inequality, and other fairly broad topics. Our hope is that, as a baseline, people come away from these workshops with a better understanding of what data can tell them about their city, and the kinds of questions other people are using data to answer. In some cases, participants move far beyond that rudimentary understanding, and work directly with BARI to find datasets, decide on tools and methodology, and generally familiarize themselves with urban science and geospatial data.

It’s always a challenge to make open data truly open to all, and it takes more than simply establishing policies allowing anyone to download a dataset. Instead, we need to meet people where they are–both technologically and geographically–and work with them to answer their questions, relate “our” data to their experience, and understand the lens through which they view their own neighborhood.