Five takeaways from a new campaign finance report

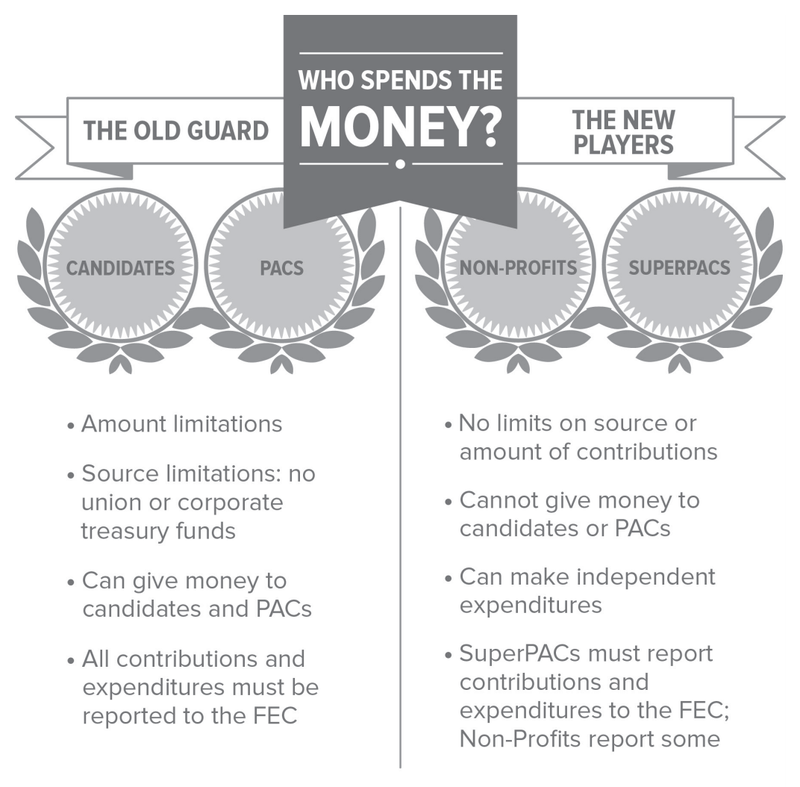

The campaign finance legal landscape has changed quite a bit in the last few years. That much is clear.

But how? A new report from Daniel Tokaji and Renata Strause at The Ohio State University’s Election Law @ Moritz is out today, and it provides an excellent overview. “The New Soft Money: Outside Spending in Congressional Elections” is based on interviews with former members, campaign operatives and other staffers. It’s quite wide ranging, and worth reading in full.

But, for those who just want some highlights, I’ll share five key points I took away from the report.

- Coordination is “kind of a farce.”

- Campaigns don’t really like all the outside money.

- Outside money operates more like a stick than a carrot on policy.

- Outside money probably makes nasty partisanship even more nasty.

- The current disclosure system sucks.

Some of these points might be familiar to readers of this blog. But one of the key contributions of this report is that it has political operatives and politicians making these points on the record – and genuinely struggling with the new landscape.

1. Coordination is “kind of a farce”

Legally, campaigns and independent groups like super PACs are prohibited from coordinating. After all, that’s what makes them “independent groups.” But as this report reveals, there is a delicate dance to coordination. And operatives have figured the moves.

The primary move in the coordination two-step involves changing partners. As one operative said: “It’s all operatives moving back and forth between the parties and the groups and the campaigns – and it’s mostly people who can finish each other’s sentences.”

Here’s former Sen. Kent Conrad, D-N.D., calling the idea of independence “nonsense”:

So this whole idea well, oh, they don’t coordinate, therefore it’s really independent is just nonsense. If you look at who makes up these organizations, on all sides, they’re loaded with political operatives. They know the way these campaigns are run, modern campaigns. They can see for themselves what’s up on the air. They can see the polling, a lot of it’s public. Some of it’s, you know not public but pretty much the same thing as what’s public. So they don’t need to talk to anybody in the campaign in order to know what to do.

And here’s an anonymous campaign operative, saying more or less the same thing: “At the end of the day, it’s all just kind of a fiction – it’s just kind of a farce, the whole campaign finance non-coordination thing.”

Sometimes the dance involves an outside group leading, and a candidate following. That is, candidates look to see what outside groups might be around and willing to step in, and then try to appeal to those outside groups. Here’s former Rep. Joe Walsh, D-Ill., explaining how the potential of outside groups stepping in shaped his campaign strategy:

I think early on that summer you begin to hear of or learn of other outside groups or individuals or interests who may have an interest in helping. And, you know, again, … it’s my downfall … [I] can’t tell a lie. You factor that into how you’re going to run your campaign. You don’t for sure know that this big wealthy guy’s coming in but you’ve heard he is. You don’t exactly know how much he’s going to spend, but you look at what you have to do, what Duckworth’s going to do. And so a campaign factors it into your over – all game plan.

Operatives also described the “b-roll” trick that Jon Stewart recently called attention to with his “McConnelling” segment. As Tokaji and Strause explain, “The most common signaling tactic we heard about in our interviews was the quiet release of ‘b-roll,’ high-resolution photographs, and targeted talking points, either available through a hidden link on the campaign’s website or through some other microsite or YouTube account.”

2. Campaigns don’t like all the outside money

It might come as no surprise to learn that campaigns would rather be in charge of the money themselves.

The “campaign lost control of the message,” said one staffer. Another said that candidates had become “bit players in their own campaigns.” The result, said one operative, was that the campaign was “dumber and sillier.” Campaigns also complained about “cookie-cutter” ads that were not aligned with individual candidates.

They complained of the awkward coordination dance. They complained that the outside groups made the campaigns nastier and more “scorched earth.”

Whether these complaints will motivate politicians to try to do something about all the outside money, however, is unclear.

3. Outside money operates more like a stick than a carrot on policy

The current thinking among conservatives on the Supreme Court is that the only reason to regulate campaign finance is to prevent quid pro quo corruption.

On that front, there are no smoking guns in this report. Tokaji and Strause note, “We did not find evidence of quid pro quo corruption, in the form of exchange of money for political favors.” That is, nobody interviewed admitted to or witnessed any activity in direct response to outside money.

But while there were no carrots, there was the ever-present stick. Numerous operatives and members described a looming threat of money coming in to oppose them.

Here’s former Sen. Bob Kerrey, D-Neb.: “The question you’re asking is do they threaten you, and the answer is they don’t have to. They threaten you — they’re threatening because you know what they can do.”

Staffers said the threat of money leads many politicians to be “extremely cautious” with positions they take. Former Sen. Conrad said that outside spending caused members to start “trimming their sails.”

As to the question of corruption, Sen. Kerrey had this amazingly tortured/candid response:

There’s a big difference between corrupt and corruption … Corruption implies a state, a constant state where everybody is groveling and everybody is behaving in almost a bestial fashion. Whereas corrupt is, I make a decision to say something that I don’t really believe. I make a decision to vote on one issue that’s different than what I really – or I just don’t examine it any further. I persuade myself that I’ve always been against raising the minimum wage and people are contributing to me because I’ve always been against raising the minimum wage. But the fact is I’ve closed my mind off to any thought of voting to raise the minimum wage because I know it’s going to cut off a significant amount of financial support if I do. That’s what I’m saying. I say it’s corrupting as an impact upon what you’re willing to at least consider as the possible right course of action.

Translation: He thinks maybe the money has altered his values and priorities. But he can’t pinpoint exactly how it happened. Didn’t he always have those values? Or did he? Well, nevermind. No use dwelling on it.

4. Outside money probably makes nasty partisanship even more nasty

Since much of the outside money is ideological, it is targeted at influencing primaries. Former Rep. Dan Boren, D-Okla., described independent spending as “further polarizing.” He said many members are worried about primaries: “You’re pulled further and further to be 100% with that group or your party.”

Former Rep Steve LaTourette, R-Ohio, put it this way: Before 2010 — the year Citizens United was decided and super PACs began to be major players — “There was a teamwork sort of view that you can still get things done … for your district. You can get things done that you thought were good.” After 2010, “ … that broke down … nothing was getting done and it wasn’t just the ideological stuff that I was used to; it was the Farm Bill and the Transportation Bill and things that were never political before but somehow became political.”

Tokaji and Strause note that money also contributes to partisan rancor in a more indirect way. Because members of Congress spend so much time raising money, they don’t get to know each other as people. They only get to know each other as either members of the same team or members of the opposing team.

As one staffer put it: “So when you’re spending all of your time fundraising, you don’t get to know your colleagues … You don’t get to know what they think and how they reason. You’re not spending time debating issues over dinner. You also don’t hang out and have your families get to know each other. And it becomes a lot easier to demonize someone and of course the media loves that and picks it up.”

5. The current disclosure system sucks

Finally, here is the takeaway that readers of this blog will be most familiar with: Our current disclosure system is terrible.

As the report notes, “A common theme of our interviews was the dysfunction in the current system of disclosure.” And as one campaign staffer said, “I’ve been working on the FEC website for 15 years and I can’t figure out what I’m looking at – how can voters?”

Of course, there were predictable disagreements among interviewees about disclosure. Some thought that unlimited contributions were the answer: If donors could give unlimited amounts directly to candidates, they would give less to non-transparent outside groups.

Here’s former Rep. Walsh: “Isn’t it a better world if he can just give me $1 million directly? But there’s instant disclosure and you as the voter right away can see it, isn’t that a healthier world? And then you as a voter got to [get] up off your butt and get educated and if it bothers you that that guy’s giving me $1 million, don’t vote for me. But now it’s all secret and then there’s all this kind of communication and not communication. Nobody knows what’s going on.”

However, others interviewed indicated that a number of donors liked the secrecy of giving to “dark money” groups,

Asked whether unlimited donations would change donors behaviors, Rep. LaTourette: “No, they’d continue to give it to (c)4s as long as we were able.” He should know. His Main Street Partnership is a 501(c)4 organization.

Though the report refrains from policy recommendations, Tokaji and Strauss note: “Many of our interviewees favored the expansion of disclosure requirements.”

Of course, there is much more in this report. It’s most definitely worth sitting down with for a few hours.