Fixed Fortunes: Biggest corporate political interests spend billions, get trillions

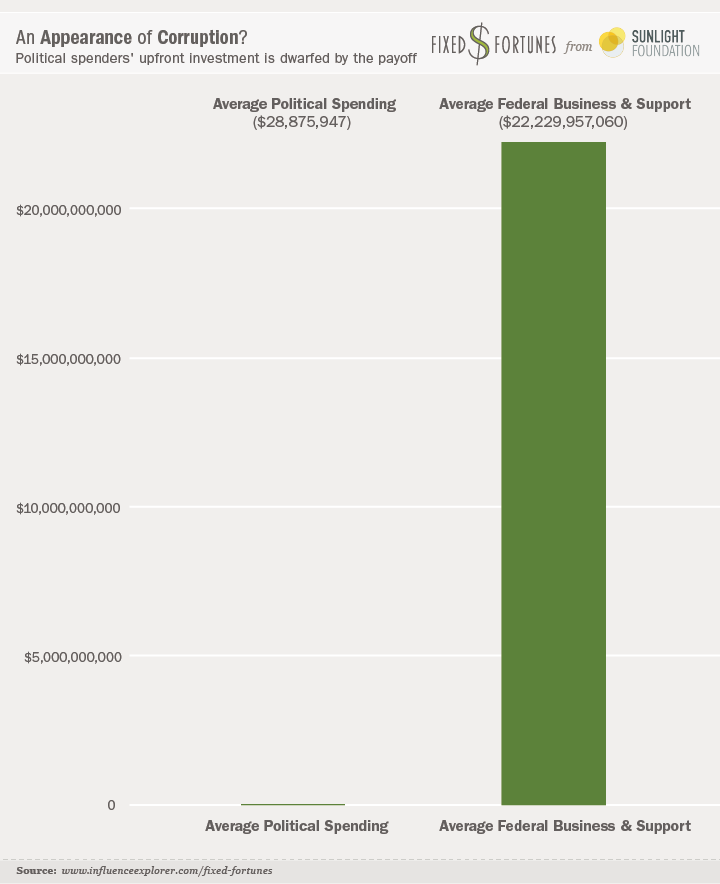

Between 2007 and 2012, 200 of America’s most politically active corporations spent a combined $5.8 billion on federal lobbying and campaign contributions. A year-long analysis by the Sunlight Foundation suggests, however, that what they gave pales compared to what those same corporations got: $4.4 trillion in federal business and support.

That figure, more than the $4.3 trillion the federal government paid the nation’s 50 million Social Security recipients over the same period, is the result of an unprecedented effort to quantify the less-examined side of the campaign finance equation: Do political donors get something in return for what they give?

Four years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court suggested the answer to that question was no. Corporate spending to influence federal elections would not “give rise to corruption or the appearance of corruption,” the majority wrote in the landmark Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission decision.

Sunlight decided to test that premise by examining influence and its potential results on federal decision makers over six years, three before the 2010 Citizens United decision and three after.

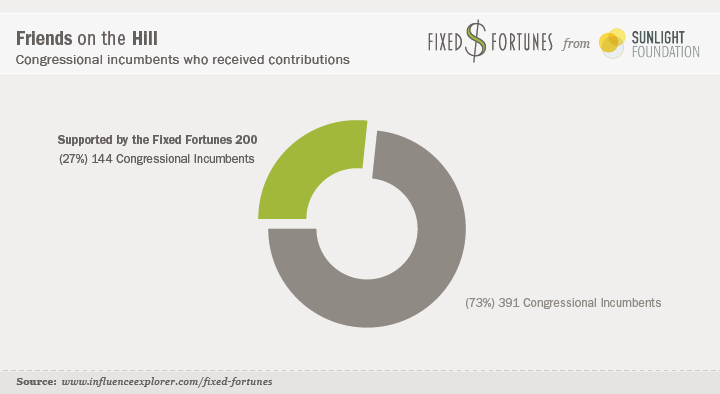

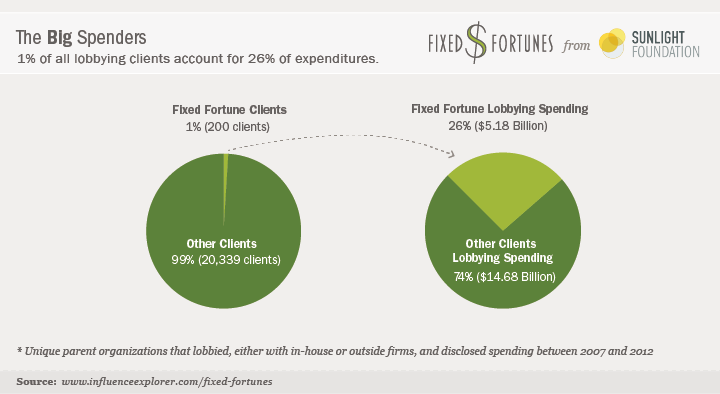

We focused on the records of 200 for-profit corporations, all of which had active political action committees and lobbyists in the 2008, 2010 and 2012 election cycles — and were among the top donors to campaign committees registered with the Federal Election Commission. Their investment in politics was enormous. There were 20,500 paying lobbying clients over the six years we examined; the 200 companies we tracked accounted for a whopping 26 percent of the total spent. On average, their PACs, employees and their family members made campaign contributions to 144 sitting members of Congress each cycle.

After examining 14 million records, including data on campaign contributions, lobbying expenditures, federal budget allocations and spending, we found that, on average, for every dollar spent on influencing politics, the nation’s most politically active corporations received $760 from the government. The $4.4 trillion total represents two-thirds of the $6.5 trillion that individual taxpayers paid into the federal treasury.

Welcome to the world of “Fixed Fortunes,” a seemingly closed universe where the most persistent and savvy political players not so mysteriously have the ability to attract federal dollars regardless of who is running Washington.

Political change, permanent interests

During the six years we studied, newly elected Democratic majorities took control in the House and Senate. Two years later, the White House shifted from Republican to Democratic control, and two years after that the GOP came back to take the House. The collapse of the housing bubble in 2007 led to massive bailout efforts by the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve Board, two massive stimulus bills and the loss of more than eight million jobs. Congress passed laws that overhauled health care insurance and financial industry regulation. Troops surged in Afghanistan and withdrew from Iraq. There were 16 separate “continuing resolutions” to fund the government, a debt ceiling standoff that caused a downgrade in the nation’s credit rating and a “super committee” to wrestle with the federal budget. As middle class Americans lost ground, the Fixed Fortune 200 got what they needed.

What they needed included loans that helped automakers and banks survive the recent recession while many homeowners went under. It included full funding and expansion of federal programs started in the 1930s that, year after year, decade after decade, help prop up prices for agribusinesses and secure trade deals for our biggest manufacturers. It included budget busting emergency measures that funneled extra dollars to everything from defense contractors to public utility companies to financial industry giants. The record suggests that the money corporations spend on political campaigns and Washington lobbying firms is not an unwise investment.

The Fixed Fortune 200 come from a wide range of industries. There are a host of familiar names among them, like Ford Motor Company, McDonald’s and Bank of America, as well as some less famous, like MacAndrews & Forbes, the Carlyle Group and Cerberus Capital Management. (For the complete list, including what they gave and what they got, click here.) There are retailers and investment banks, construction and telecommunications firms, health insurers and gun makers, entertainment conglomerates, banks and pharmaceutical manufacturers, among others.

Overall, the Fixed Fortune 200’s PACs, employees and their family members gave $597 million to political committees and disclosed spending $5.2 billion on lobbying. They make this enormous investment in politics in large part because their businesses are inextricably entwined with government decisions — including spending decisions.

Government as business partner

For example, the federal government issued contracts to purchase goods and services that totaled a little more that $3 trillion during the period; companies among the top 200 corporate political givers won $1 trillion of that, a third of the total. The Treasury Department managed $410 billion in loans and other assistance issued under the Troubled Asset Relief Program, created by Congress to cope with the 2008 financial crisis; of that amount, $298 million, about 73 percent, went to 16 firms among the Fixed Fortune 200. When the Federal Reserve took extraordinary measures in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, it funneled nearly $2.8 trillion through 29 Fixed Fortune firms. The companies that participated the most in politics got huge returns.

Of the 200 corporations we examined, we could sum the financial rewards for 179. Of those, 138 received more from the federal government than they spent on politics, 102 of them received more than 10 times what they spent on politics, and 29 received 1,000 times or more from the federal government than they invested in lobbyists or contributed to political committees via their employees, their family members and their PACs.

As for the other 21 companies on our list, while we could not quantify the financial benefits that some received, we were able to identify them. Some examples:

- Arch Coal lists the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), the government corporation that’s the largest public electricity producer, as one of its three biggest customers. TVA does not release data on its coal purchases.

- Forest City Enterprises does not appear as a landlord in the Government Services Agency’s database of federal rental agreements, though its annual report notes that the U.S. government is the third-biggest customer for its pricey New York City office space.

- Occidental Petroleum has leases on federal land to extract natural gas, but the government does not release information on how much that gas is withdrawn or how much it is worth.

- And while the government has so far refused to release information on what retailers get the most purchases via food stamps, Wal-Mart went so far as to acknowledge in a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission that reductions in the now $78 billion-a-year Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program — or food stamps — could have a significant impact on the company’s earnings, which totaled $476 billion in its most recent fiscal year.

Of the 200 companies analyzed for Fixed Fortunes, 28 are in what the money in politics research organization the Center for Responsive Politics classifies as the communications and electronics sector, 21 in healthcare, 13 in defense and aerospace, 13 agribusinesses, 11 in energy and natural resources, and 7 in transportation. The biggest sector, accounting for 48 of the 200, was finance, insurance and real estate, which is consistently the largest source of campaign funds for politicians cycle after cycle. Congress and the executive branch have paid particular attention to the industry, approving hundreds of billions in aid to help it weather the financial crisis. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve advanced trillions in credit, which the nation’s central bank hoped would trickle down through the rest of the economy.

Companies with the biggest returns on their political investments include three foreign financial service and banking firms, UBS and Credit Suisse Group from Switzerland, and Deutsche Bank of Germany, all of which benefited from the Treasury Department’s taxpayer-financed rescue of American International Group. Investment banks Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley as well as commercial banks like JPMorgan Chase & Co., Citigroup, Wells Fargo and Bank of America also received far more from government than they put into politics: They benefited from the bailouts of the financial industry undertaken by Treasury and the Federal Reserve. Weapons manufacturers like Boeing and Lockheed Martin, both of which disclosed spending more than $10 million each year on lobbying, also made the list. So did McKesson, a pharmaceutical wholesaler that is the biggest vendor for Veterans Affairs, and the Carlyle Group, a wealth management firm started by former government insiders who invest in firms that have significant involvement with government, such as defense, telecommunications and health care.

A range of returns

To catalogue the money flowing to and from the Fixed Fortune 200, we examined data on campaign contributions and lobbying expenditures. We compiled and queried a host of government spending records, including spending approved through the normal budgeting process. We also looked at additional spending measures — extra-budgetary spending on the Global War on Terror, renamed Overseas Contingency Operations in 2009, and emergency or one-time measures like the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. And because the Federal Reserve made use of its power to advance credit to private firms in extraordinary circumstances, we also examined its interventions in the economy.

See our methodology for a complete explanation of how we arrived at these numbers and more.

Some of the gets are harder to quantify. While corporate interests disclose lobbying on federal spending — the budget and appropriations process — more than any other issue, they also seek to influence trade agreements, labor rules, environmental regulation and the Internal Revenue Code.

Blue Cross and Blue Shield has its own provision in the tax code, section 833, that saves its companies an estimated $1 billion a year. Life insurance companies like New York Life and Pacific Mutual, and their customers, are eligible for tax breaks that save the industry $30 billion a year, with about $3 billion going to the companies and the balance going to their policyholders. The corporate tax code is full of loopholes and subsidies that companies lobby for to help their bottom lines; Citizens for Tax Justice researched the Securities and Exchange Commission disclosures filed by publicly traded corporations in an effort to determine their effective tax rates; its analysis included 89 members of the group Sunlight examined. The average effective tax rate of those companies was 17.7 percent between 2008 and 2012. Federal law, meanwhile, sets the corporate tax rate at 35 percent.

As far as we can tell, one thing the Fixed Fortune 200 did not do, for the most part, was take advantage of the new opportunities to spend on politics that the Citizens United decision afforded them. The 200 corporate donors gave just $3 million to super PACs, with the bulk of that amount a single $2.5 million donation from Chevron to the Congressional Leadership PAC, a super PAC that’s been linked to House Speaker John Boehner. It’s important to note, however, that contributions by these companies to politically active nonprofits (a category that includes the Chamber of Commerce) are impossible to track because of tax laws that allow those entities to shield donors.

Though beyond the scope of our study, which focused on the federal government, it is worth noting that 174 of the 200 corporations won subsidies from state and local governments, according to Good Jobs First, an organization that tracks economic development programs. The Citizens United decision also applies to state election laws, giving corporations the right to speak at the state and local levels as well.

Nonetheless, opinion polls show that majorities of Americans generally trust governments in their city halls, township boards and state capitals. That doesn’t compare well to the mere 19 percent of Americans who trust their federal government. Frustration with Washington runs high for any number of reasons, but consider:

- Two-thirds of Americans believe corporations pay too little in taxes and that they should pay more, but tax reform stalls in Congress year after year;

- Prominent politicians from both parties have criticized corporate welfare programs that benefit big business for more than two decades, but not one of those programs has been repealed;

- The president and Congress ended a reduction in payroll taxes that benefited wage earners in January 2013 but extended business tax breaks for insurers, energy companies and other corporations;

- Federal bailouts returned financial industry firms that started the crisis to profitability, while middle class income and net worth of the middle class fell.

More than seven years after Washington passed the first measures to stimulate the economy as the housing bubble started to burst, more and more Americans are living on less and less, without as much savings and other assets to fall back on in hard times. Washington policies that have restored corporate profits and made the stock market boom have left much of the country behind. Perhaps that’s why a whole host of polls, from networks and news organizations and nonprofit groups, show large majorities of Americans, year after year, saying that the country is on the wrong track.

In its Citizens United decision, the court took for granted that “favoritism and influence” are inherent in electoral democracy and that “democracy is premised on responsiveness” of politicians to those who support them. We found ample evidence of that.

“The appearance of influence or access,” the court said, “will not cause the electorate to lose faith in our democracy.”

It appears that the electorate — who stayed away from the polls this year in droves — might not agree.