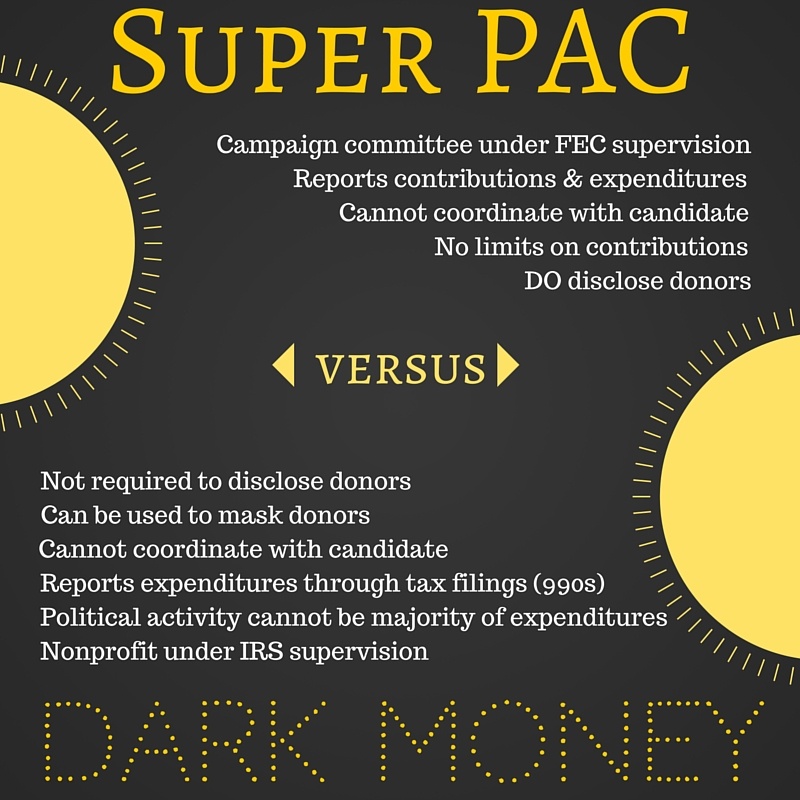

The difference between super PACs and dark money groups

After an investigative report by The Washington Post revealed several super PACs acting in support of his campaign, Donald Trump acted swiftly, condemning the activities of the super PACs and ordering his attorneys to send cease and desist letters to several groups.

This action, as well as the placement of television ads by a dark money group supporting Marco Rubio, has triggered a debate within the Republican party about the impact of money in the election, with both Trump and fellow GOP hopeful Jeb Bush taking swings at each other about the influence of dark money in the election.

We were glad to hear candidates having a spirited discussion about the role of money in the 2016 election cycle. However, a lot of the headlines mentioned Trump rejecting “dark money” in particular. (Probably because the title of his press release was “Donald J. Trump Calls On All Presidential Candidates to Return Dark Money Sent to Super PACs.”)

We reached out to the Trump Campaign for clarification; what exactly did Trump mean when he used the term dark money? Press contact Hope Hicks confirmed that Trump means all money given to super PACs in particular; however, like other political action committees, super PACs do have to file regular financial disclosure forms with the Federal Election Commission, including the source of donations and the amounts given. That’s why we generally refer to super PAC funds as “unlimited money.”

Here’s the huge caveat: Because super PACs are permitted to accept money from entities that do not have to make the sources of their funding public, such as 501(c)(4) groups, it’s possible for them to keep the names of actual donors hidden from the public. We call this “dead-end disclosure.”

Since campaign finance can be a complicated issue, we thought we would do a quick 101 for super PACs versus dark money for the 2016 election cycle.

Here are some of the key characteristics of unlimited money from super PACs, also referred to as “independent expenditure groups.”

- No limit on the dollar amount of contributions

- Do disclose donors

- Cannot coordinate with or donate money to candidates

- Federal Election Commission has jurisdiction over these organizations

- In election years, file reports on donors either monthly or quarterly, as well as reports on independent expenditures within either 24 or 48 hours (based upon the date and amount of the expenditure); in nonelection years, file reports on donors monthly or semi-annually, as well as reports on independent expenditures within either 24 or 48 hours (based upon the date and amount of the expenditure)

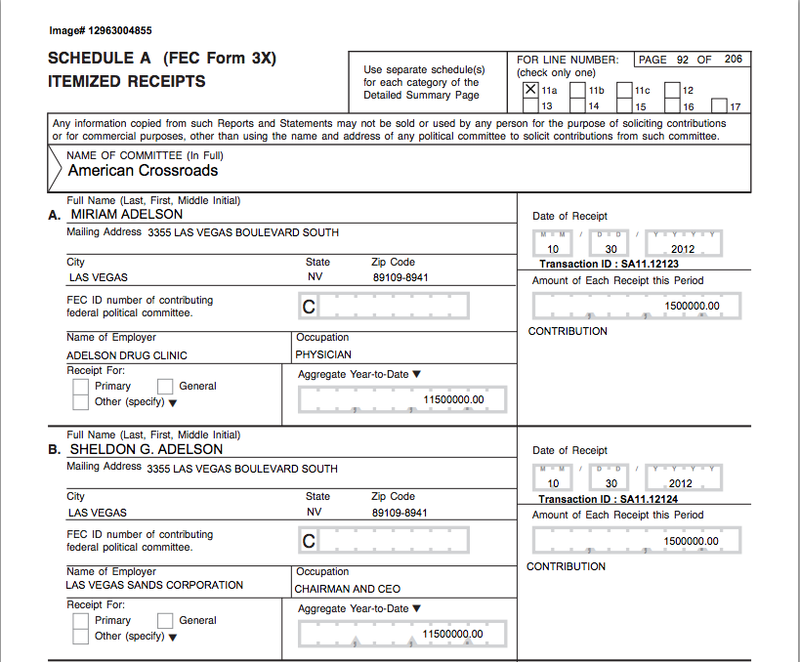

Here’s an example of a super PAC disclosure form from the FEC, Karl Rove’s American Crossroads. Note how each donor is listed out with specific details:

Now, let’s turn to dark money. When we use the term “dark money,” we mean money coming from 501(c) organizations, named after their identification in the tax code. These include social welfare groups, unions and trade organizations registered with the IRS. Recently, the focus has been on 501(c)(4) social welfare groups, since the Citizens United ruling empowered these nonprofits in particular to participate in politicking much more actively. (Here’s a great rundown of 501(c)(4) groups from our friends at OpenSecrets.org if you want greater detail.) Some characteristics of these groups:

- No limit on the dollar amount of contributions

- Do NOT have to disclose their donors

- Cannot coordinate with or donate money to candidates

- IRS has jurisdiction over these organizations

- May participate in nonpartisan political activity providing a “majority” of their activity go to “social welfare” activities. (It’s widely accepted that this means at least 50.1 percent of their efforts must go toward social welfare activities, which are broadly defined by the IRS.)

- Report their spending through 990 IRS tax forms, which are typically delayed by a year or more and often long after the elections have ended; 990s often show major vendors these nonprofit hire and what groups they give money to, but are not obligated to say what the money purchased with any specificity. (However, 501(c) groups must report independent expenditures to the FEC as well.)

- Campaign donations are sometimes funneled through these organizations to super PACs to mask donors

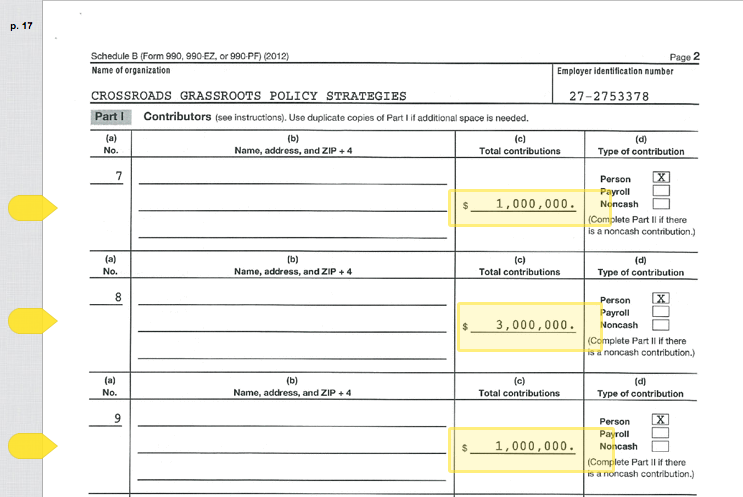

Here’s an example of a dark money disclosure form, courtesy of ProPublica. In this case, it is American Crossroads’ sister organization, Crossroads GPS.

Note how few details are released; only the dollar amount is available, even though these are big-money contributions.

The nuances of these two terms become important when you look at the attacks happening between fellow Floridians Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio. After the most recent filing deadline, Rubio’s campaign bragged that it had more cash on hand than the Bush Campaign.

A Bush spokesman fired back with this tweet:

Haven't seen the Rubio press release on frugality did it include the $6 million in secret money TV ads they saved money on?

— Tim Miller (@Timodc) October 15, 2015

Most of Rubio’s television advertising has been funded by a 501(c)(4). The only reason we know about how much they are spending is because, under FCC rules, broadcasters are required to keep information about who is buying ads on their stations and make them available to the public online. This is one of the only ways to pick up on how dark money groups are getting involved in elections. However, there is no standardization of what information broadcasters are required to file making it often difficult to figure out who is behind the dark money groups.

Bush has advocated for unlimited money in elections, but requiring disclosure of donors as well as reporting contributions within 48 hours of receipt. However, it should be noted that Bush also has a 501(c)(4) dark money group, Right to Rise Solutions, supporting him as well. We have not yet seen that organization run ads on Bush’s behalf, though a pro-Bush super PAC is quite active in Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina.