American cities depend on federal data

A Sunlight Foundation survey of staff in 63 American cities reveals that data collected and published by the federal government is a crucial resource for local communities.

Federal data is uniquely important to cities. The federal government collects information on things like population, household incomes, race and ethnicity, public health, and economic activity, among many others, that municipalities cannot. In some cases it is simply more efficient for the federal government to collect this information. “It’s beyond our ability to track global climate trends,” as one city staffer put it. In other cases, having cities collect this data themselves would be inappropriate. “Can you imagine if we made national decisions based on every city’s independent estimate of their population?” another pointed out.

Cities use federal data to inform all kinds of decisions at the local level. Federal data helps cities make choices about how to allocate resources and prioritize projects. Federal data also helps cities understand how they are performing over time and how they compare to other cities across the country.

This type of data-driven, evidence-based decision making is a core part of accountable, efficient, and effective government. The Sunlight Foundation and our partners at What Works Cities are dedicated to helping cities across the country incorporate this approach into their own work. Federal data is a key part of this.

However, there are a lot of open questions about how federal data will continue to be collected, maintained, funded, and shared under the Trump Administration. Trump still has not nominated anyone to run the Census Bureau. Nor has he appointed a chief technology officer or chief data scientist, and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy has been effectively gutted. Meanwhile, ProPublica raised concerns that the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which publishes data on the housing market and housing affordability, could be dismantled under the current administration. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which publishes the nation’s monthly jobs report, has seen its funding fall by nearly 10 percent since 2005 after adjusting for inflation. And the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, which collects national transportation data, has seen its budget decline by 21 percent and has been unable to collect data on the number of trucks and their use in the United States. All of this should ring alarm bells for cities that rely on data from the federal government.

Meanwhile, members of Congress are questioning programs like the American Community Survey — an information resource which nearly every American city uses. The 2018 Economic Census has been delayed, and the 2020 decennial census is facing “urgent” budget shortfalls. Earlier this month, the NAACP sued the Department of Commerce for allegedly withholding records about its preparations for the 2020 census. “The Census Bureau routinely undercounts communities of color, young children, home renters, low-income persons, and rural residents,” NAACP general counsel Bradford M. Berry said in a statement. “But all signs indicate that the 2020 Census will be a particularly egregious failure on this front.”

In the midst of these discussions, news stories often turn to business leaders to provide perspective on why this data matters. Yet despite the fact that they are likely among the largest users of federal data, the perspectives of city halls are rarely included in these debates.

As federal policymakers consider changes to federal data, members of Congress and federal agencies should understand how important federal data is to cities, and consult with them about how these changes would impact their ability to serve Americans locally.

To help shed light on just how important federal data is to cities, the Sunlight Foundation, in partnership with Kate Rabinowitz at DataLensDC, conducted a national survey of municipal staff about how federal data informs their work. The survey was sent out to hundreds of municipal staff. There were 118 respondents from 63 cities. Respondents come from cities of all sizes and a wide range of departments including emergency services, planning and community development, city manager’s and mayor’s offices, and information technology. Survey participants are anonymously quoted throughout this document to encourage honesty and protect them. You can see the full results on GitHub.

The responses provide insights into how cities use federal data and why it is important for their work improving life for everyone in their community. Here is what we found out.

1. Federal data is crucial to cities

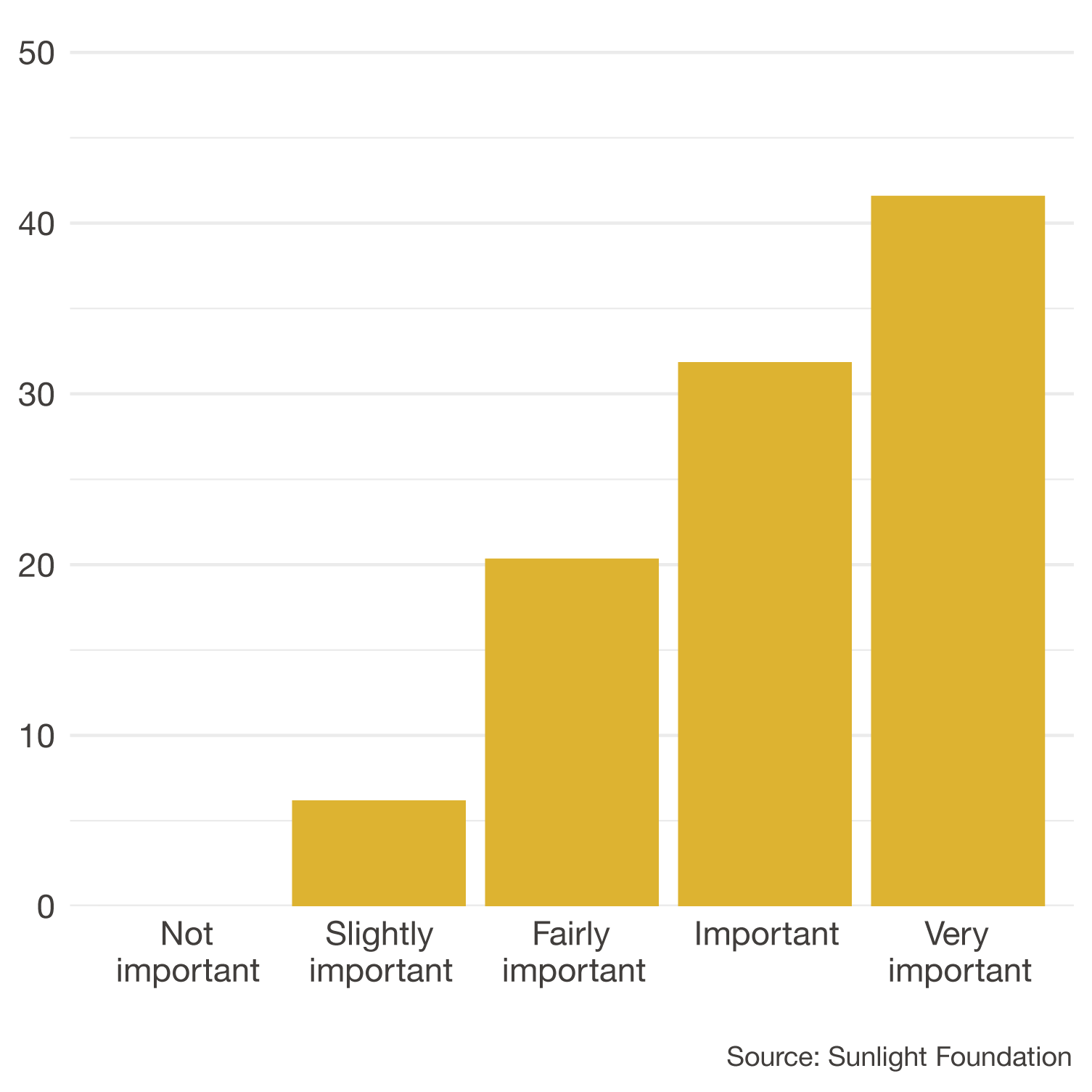

Percent of respondents

To say that federal data is important to city governments is an understatement. Federal data provides city staff with basic information about their residents, including the city’s population, income levels, race and ethnicity, and employment. And in doing so it informs many aspects of cities’ work.

Seventy-four percent of survey respondents said federal data was “important” or “very important” to their department’s mission. Federal data was most important to mission in planning and development departments, as well as innovation and analytics departments.

CITY VOICES

2. Data on demographics, housing, and the economy are used most frequently

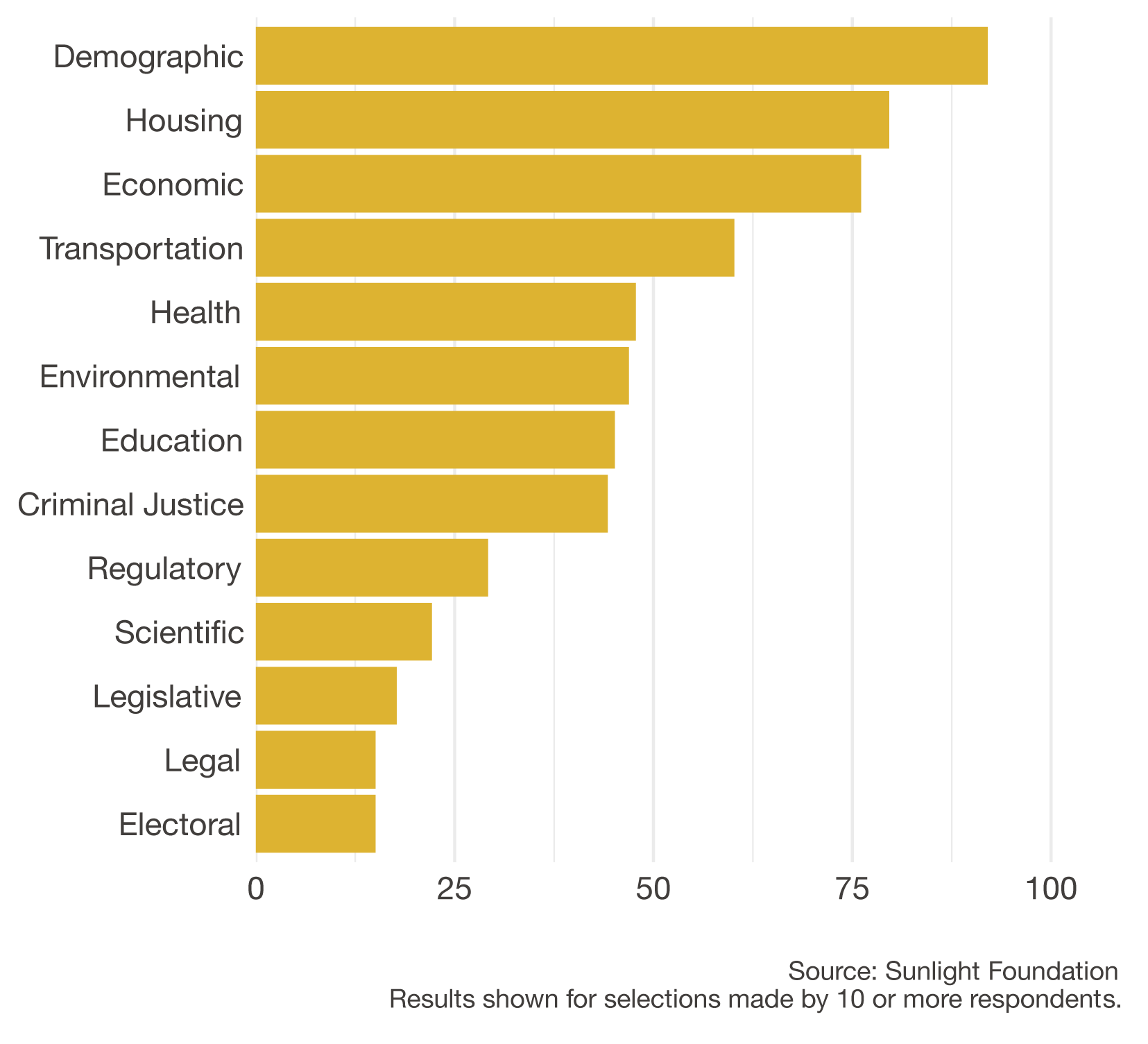

Percent of respondents

The federal government publishes a wide range of data on topics from fruit prices to affordable housing. The data most popular with city staff who responded to our survey falls into four categories: demographic, housing, economic, and transportation. Practically every respondent uses demographic data, while three-quarters use housing and economic data. A majority use transportation data as well. Data on health, the environment, education, criminal justice, regulation, science, legislation, legal issues, and electoral issues were also highlighted by 10 or more respondents.

City workers and their departments rarely rely solely on any one type of data, however. Only four respondents indicated they use data from only one of the categories shown above. The median responder indicated their department uses data from six of the above categories. Cities face complex issues, make policy decisions that can affect their community from a number of different angles, and often operate in intricate legal and regulatory environments. The breadth of federal data available helps cities address these complexities.

CITY VOICES

3. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau is used most, by far

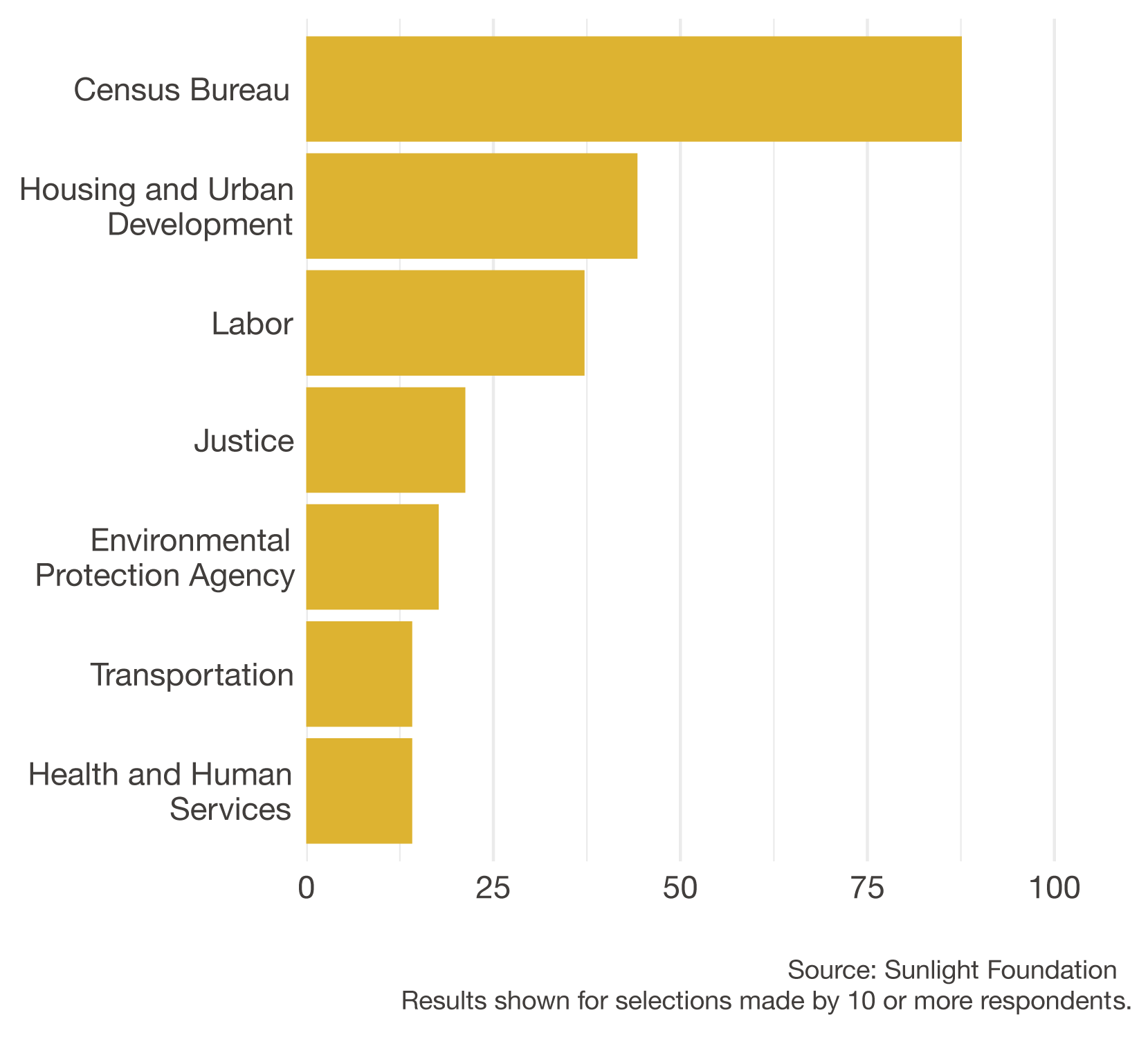

Percent of respondents

In line with demographic data being the most popular, as discussed in section two, respondents indicated they rely most on the U.S. Census Bureau for their data needs — by far. Data produced by the Census Bureau goes far beyond the decennial census. The dataset we heard the most about from respondents was the American Community Survey (ACS), an ongoing survey that includes a broad range of social, economic, housing, and demographic data. The ACS’s strength isn’t just its breadth of topics, but also its more localized information. Many city challenges are at the neighborhood level and so city workers often look to the ACS’s tract level data, the most localized type of data currently available which typically encompasses 2,500 to 8,000 people.

Nearly half of survey respondents also indicated they rely on data produced by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). HUD publishes extensive data on the housing market, housing affordability, and subsidies. In addition, HUD funds affordable housing and infrastructure projects in many cities, and respondents cited this funding as closely connected with their own data collection efforts.

The Department of Labor was also an important source of data for many respondents. The Department publishes economic data on topics including employment, wages, and prices, particularly through its Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

It is hard to overstate how widely used Census data is. Respondents explained that Census data informed everything from annual budgets to outreach efforts to long-term planning for many cities.

CITY VOICES

4. Federal data helps cities understand how they compare to one another

Survey respondents consistently mentioned that federal data helps them understand how they compare to other cities. The federal government is able to create a standard set of criteria and compare cities using that criteria in a way that an individual city or even state would not be.

This shared understanding creates a sense of competition between cities: many respondents explained that they use federal data to compare how their performance to that of their peers. However, it also creates a shared understanding among cities; a sense that they all face the same challenges and in many ways, are striving to achieve similar goals.

CITY VOICES

5. Cities make strategic decisions based on federal data

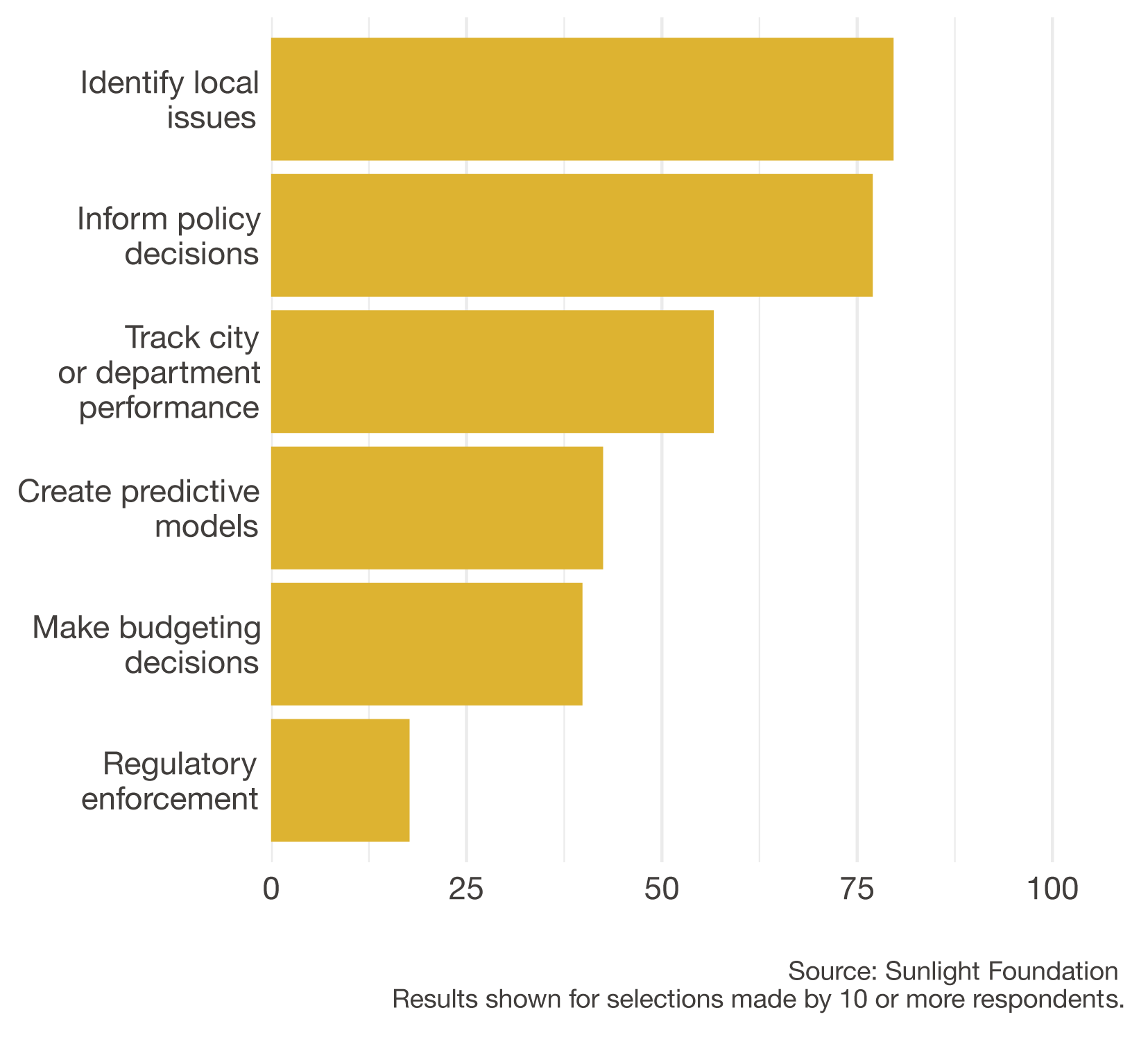

Percent of respondents

Across cities and departments, respondents most commonly used federal data to identify local issues and inform policy decisions. As an increasing number of cities shift toward evidence-based policies, federal data helps them understand what is working and what’s not. Respondents used federal data “to make key decisions on where to focus energy and money.” And without federal data,many respondents indicated policy decisions would suffer and “be made based on opinion or intuition.”

Across cities, departments are using federal data in ways that support their unique needs — sometimes in ways totally different than originally intended by the federal government. Every respondent working with emergency services indicated they were using federal data to create predictive models. The top use of federal data among city controller and auditing departments was to track city and department performance. Public works were most likely to use federal data for regulatory enforcement.

CITY VOICES

6. Cities rely on federal data more now than ever — and expect their reliance to increase

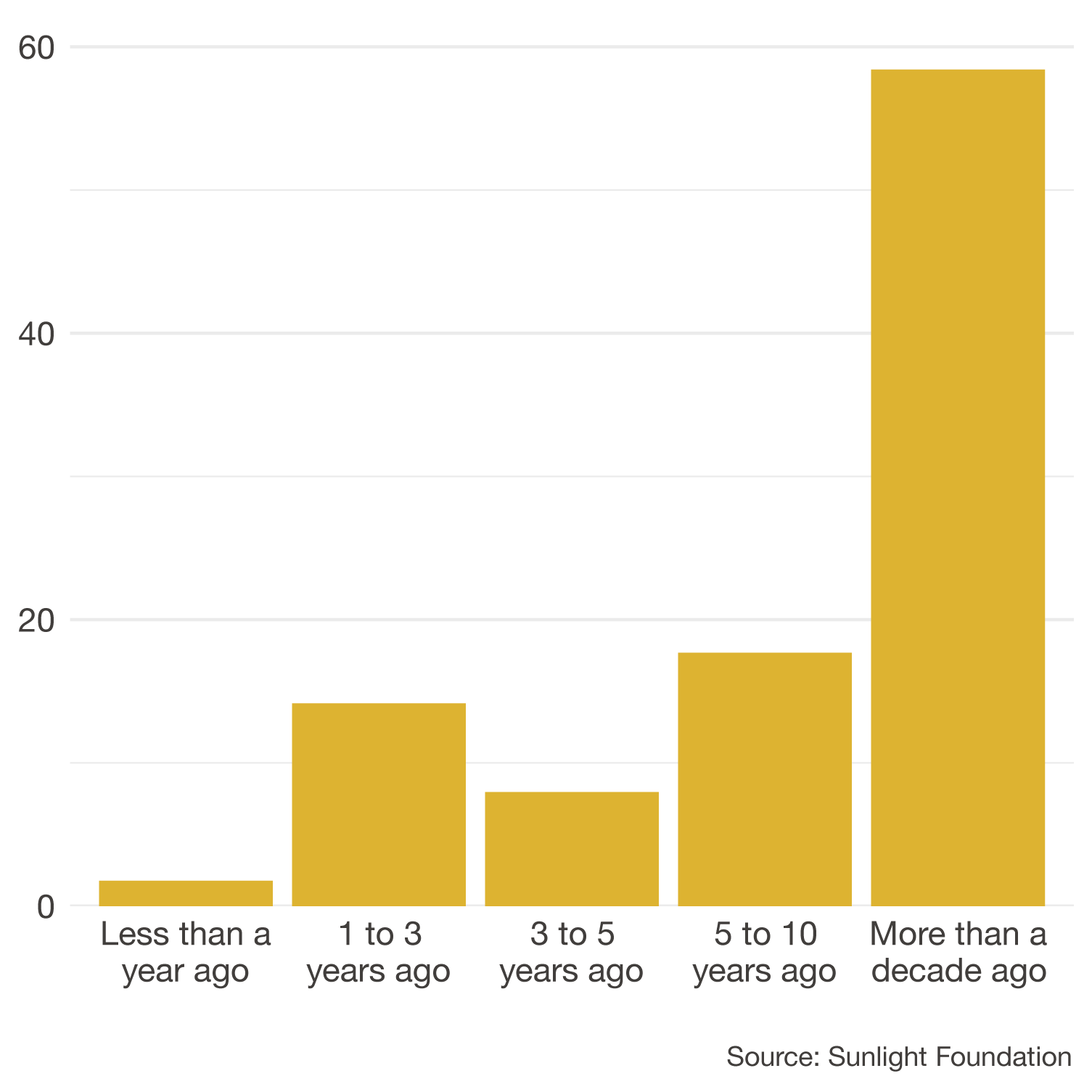

Percent of respondents

Federal data has become an integral part of many cities’ work: 56 percent of respondents say their department has now been using federal data for over a decade. City innovation and analytics departments are some of the newest teams to rely on federal data. The creation of these departments is further evidence of the investments in data-driven approaches and capacity that cities are making, and how integral federal data is becoming.

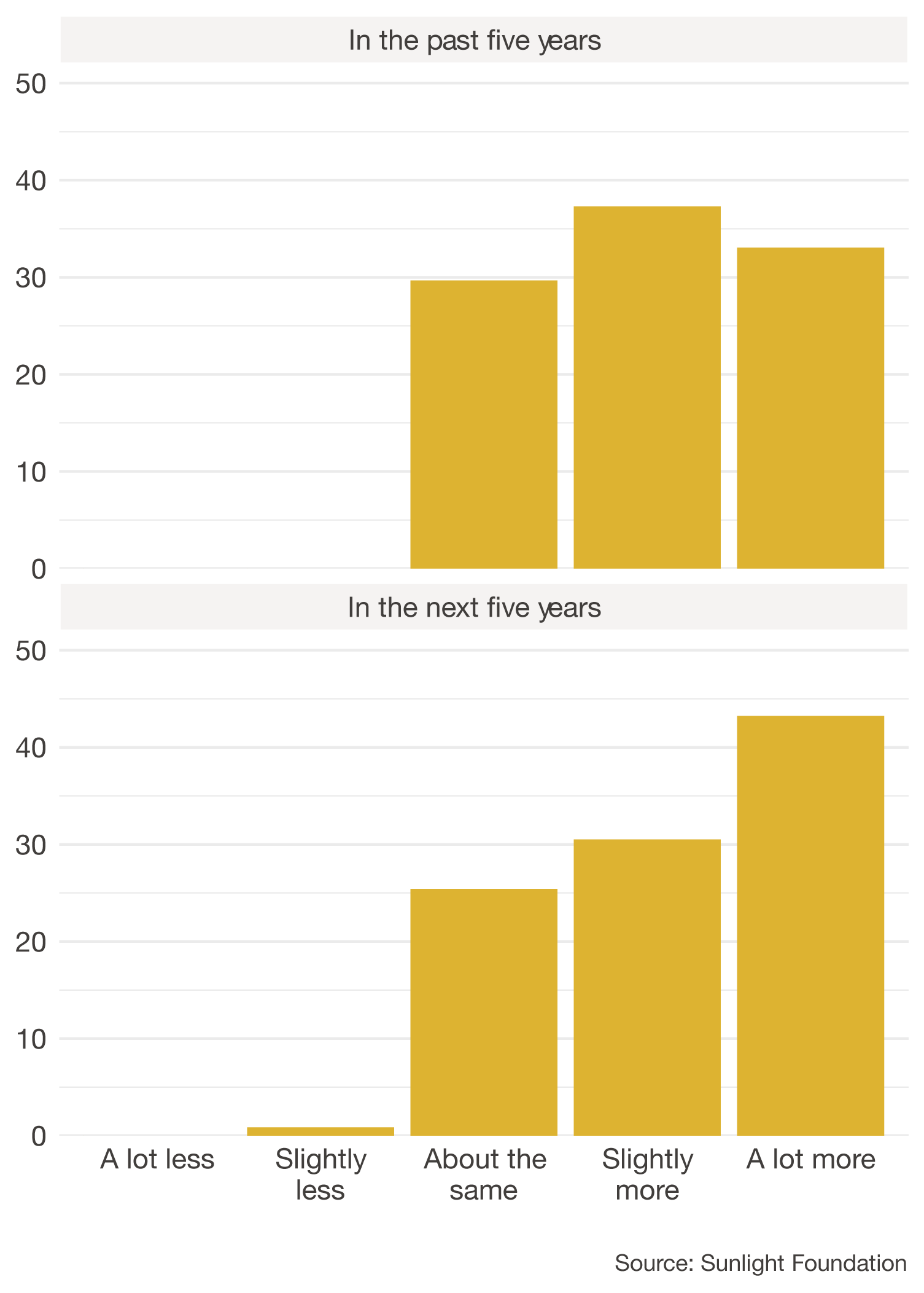

For both long-term and new users, how much cities use federal data continues to increase. One third of respondents report having used “a lot more” data in the past five years, and 43 percent plan to use “a lot more” in the five years ahead. No one reported using less federal data in the past five years. Only one respondent anticipated using less federal data in the future — and this was solely due to an expectation there would be less federal data to be available.

Percent of respondents

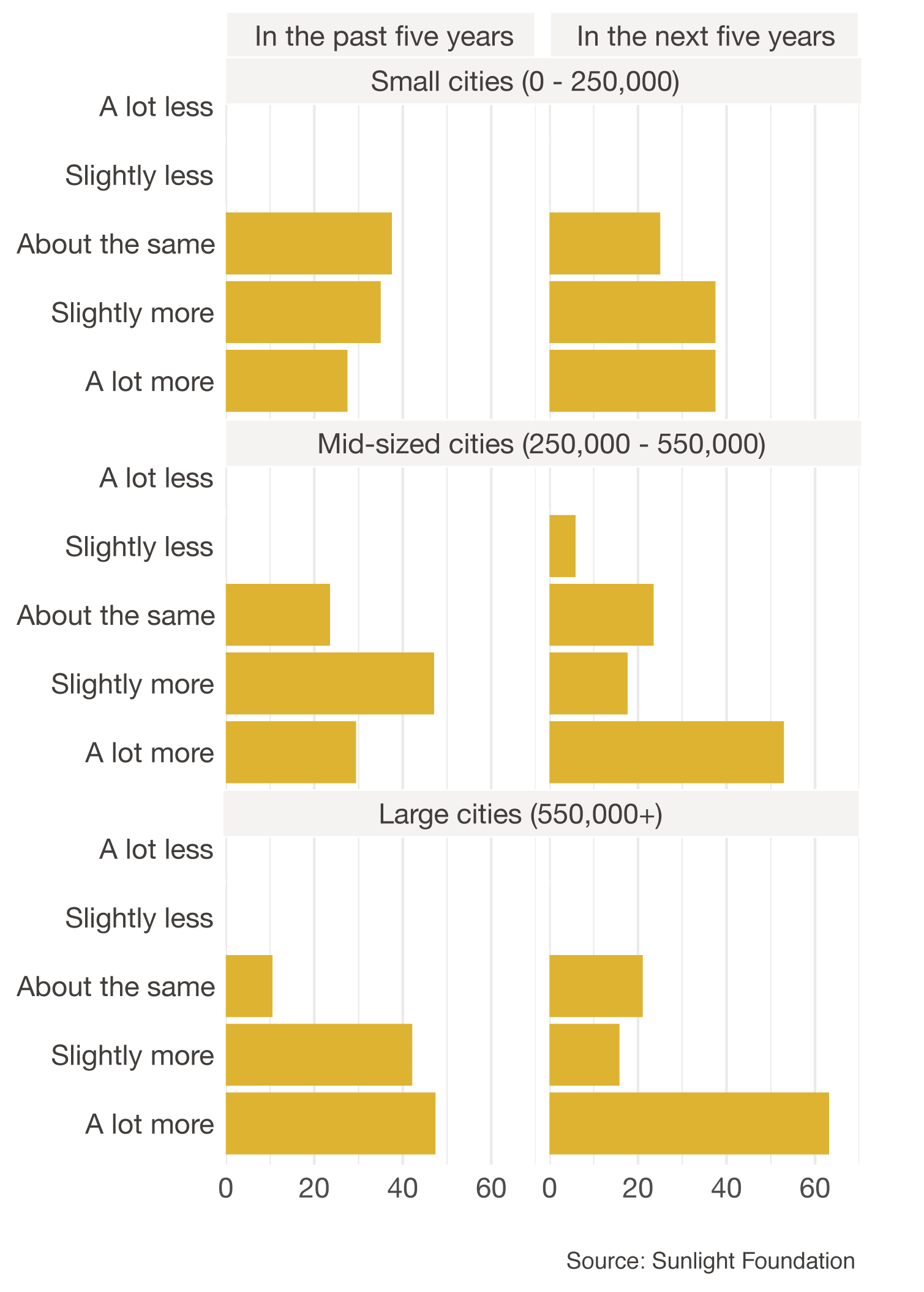

The increase in the use of federal data has been consistent across cities of all sizes. However, respondents from larger cities — those with a population of 550,000 or more — have been the most aggressive in expanding federal data use in the past five years. Going forward, more respondents of small and mid-sized cities anticipate greater growth in federal data usage.

Percent of respondents

7. Cities want more federal data

Percent of respondents

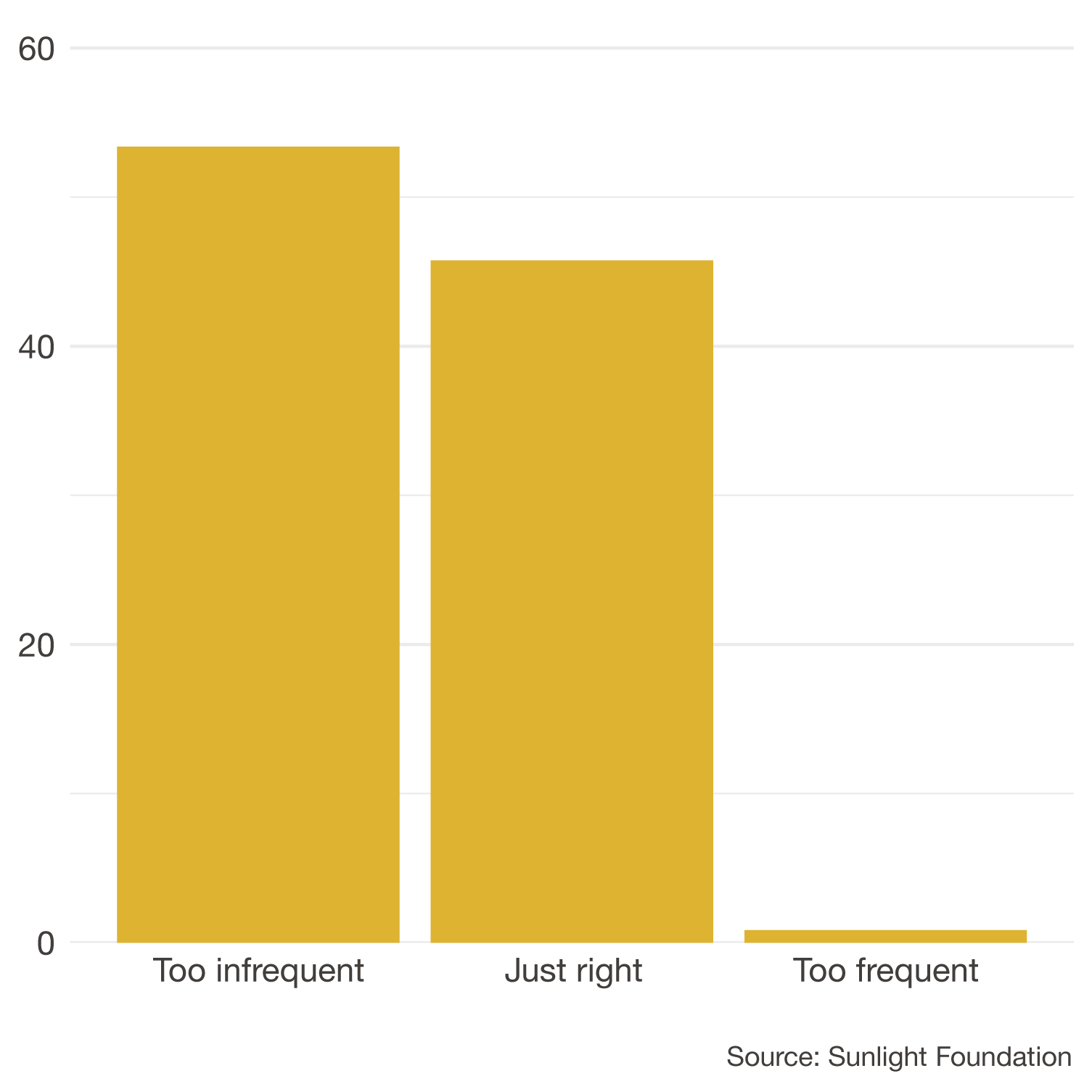

A majority of respondents stated that federal data was published too infrequently. Interest in more federal data was persistent throughout the survey. When asked about specific data needs, respondents, perhaps not surprisingly, were particularly eager for more local-level data. Respondents asked for more granular data about their communities’ health; migration; law enforcement and corrections; employment; and generally more information from the ACS.

Respondents also detailed what data the wished was available or more available, including things like broadband and the digital divide; criminal justice and persons with criminal records; employment retention; and insurance information other than health. More unique requests included one for a list of valid addresses for the entire country; one for sensor-based traffic data from interstates; and one person who — aptly — requested data about all the different datasets available from the federal government. To that final respondent, we have good news: this data exists! A catalog of all federal datasets is available from Data.gov’s Enterprise Data Inventory.

CITY VOICES

* The EPA’s web pages about climate change were deleted in May 2017. Those pages were republished on the City of Chicago’s website.

8. The federal government can improve the way it delivers data to cities

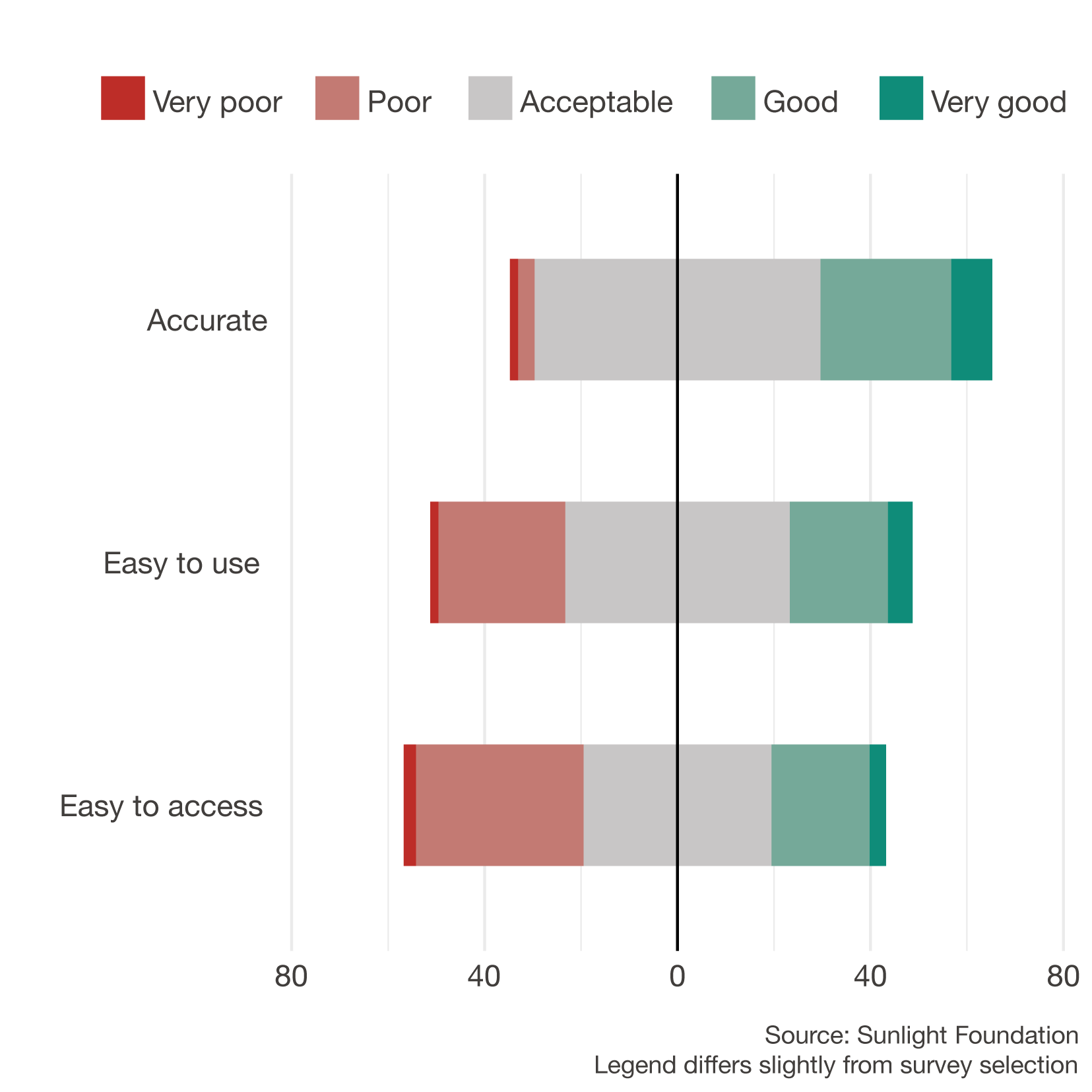

Percent of respondents

The majority of respondents have confidence in the accuracy of federal data produced today, but have challenges finding, accessing, and using that data. Thirty-seven percent of respondents reported federal data as difficult or very difficult to find and access. Twenty-eight percent similarly found using federal data to be difficult or very difficult. Respondents consistently expressed a desire for data at more granular levels, particularly at the Census tract level.

Some respondents pointed out that they could probably use more federal data, but do not know what exists. Projects like CitySDK by the Commerce Data Service aim to help narrow this “major usability gap” for city data by creating a toolset to easily combine multiple federal data sources. Unfortunately, CitySDK has been inactive since March 2017.

CITY VOICES

9. Cities are concerned about the future of federal data

Percent of respondents

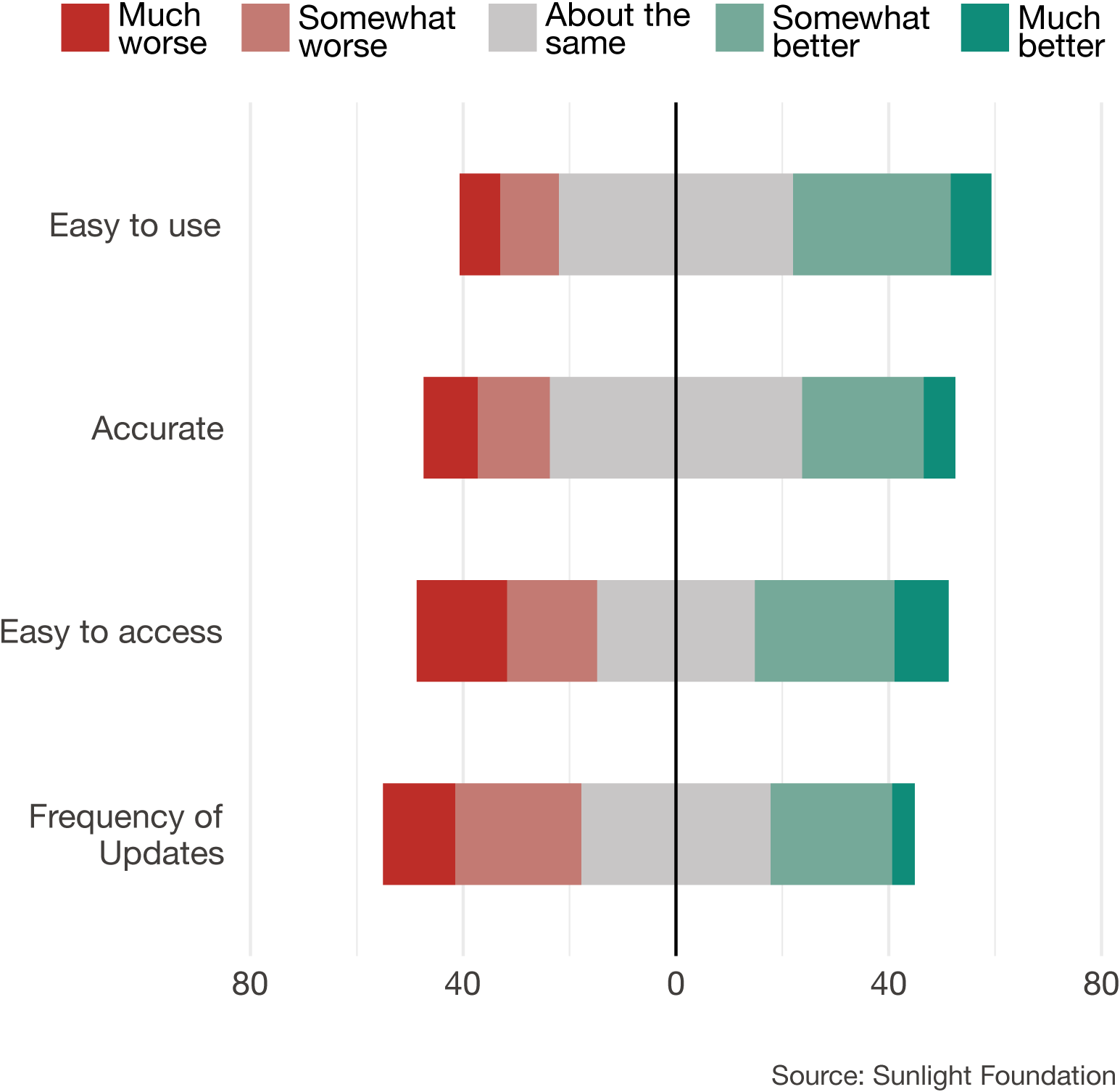

Compared to five years ago, more federal data is available online today and it is generally easier to access and use. Survey respondents, however, were not confident that this trajectory will continue.

In terms of ease of use, just over 37 percent of respondents expect federal data to become easier to use over the next five years. Forty-four percent anticipate little change at all.

When it comes to accuracy, nearly a majority expect no real change to how accurate data is today. Nearly equal numbers anticipate it getting better as well as worse. Ten percent anticipate the accuracy of federal data to become much worse. The wide spread in outlook underlies the uncertain environment caused by the current administration.

Respondents expressed a similar wide range in regard to access to federal data in the next five years. Thirty-four percent expect ease of access to federal data to worsen, while 36 percent expect it to improve.

Respondents were most concerned about the future frequency of federal data. This is the one category where more respondents anticipate a decline rather than improvement. Thirty-seven percent of respondents expect a decline in the frequency of federal data; only 27 percent think the federal government will release data more often. With a majority of respondents indicating that the current frequency of federal data is already not enough, this sets up a growing unmet need for the future.

CITY VOICES

Moving forward

There are several clear opportunities coming up that will be a proving ground for the current administration’s commitment to open federal data.

Fund the 2020 decennial census

The first is the 2020 decennial census. This Constitutionally mandated survey should be as thorough and inclusive as possible. This will require more resources than the federal government has currently allocated, and vocal support from members of Congress on both sides of the aisle.

Appoint leadership

For the federal government to effectively collect, maintain, and share critical federal data, it needs effective leadership. Trump needs to nominate someone to run the Census Bureau, appoint a chief technology officer, and a chief data scientist. And the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy should be appropriately staffed and funded.

Lead internationally

The third opportunity will be the United States’ participation in the Open Government Partnership. With an international summit coming up in just a few weeks, the Partnership will be a chance for the United States to demonstrate international leadership on data collection and dissemination.

Cities are an important part of all of these conversations. Members of Congress should consider the opinions of city leaders when debating changes to federal data programs. Members of the press should include cities in their analysis of why federal data matters. National organizations that represent the interests of cities should incorporate this into their advocacy. City staff should be vocal about how they use federal data in their work, and why these issues are important to them. And Census Bureau staff should know that cities are enthusiastic supporters of this valuable resource.

Eroding federal data programs means cities would be less able to make decisions based on evidence. That would be bad for cities as well as the American people. Conversations about why federal data is important have implications beyond the work of federal agencies and businesses. It’s time for cities to be a louder voice in that discussion.