Host Your Own TransparencyCamp

TransparencyCamp is the Sunlight Foundation’s largest and most popular community event. Its purpose is to both bridge the broad range of communities passionate about government transparency, accountability and technology in the present and to help create the policies, ideas, and technologies that will define the field’s future.

Whether you’re interested in hosting your own version of TransparencyCamp, creating a derivative, but related event, or are just scoping out new approaches to “unconference” organizing, this guide is for you. The first section offers an introduction to TransparencyCamp, it’s history and foundations. The second goes into details on organizing an open space or unconference event and is intended to help first-time and veteran organizers alike.

The History of TransparencyCamp

Since its founding in 2006, Sunlight Foundation — a nonpartisan, nonprofit based in Washington, DC, working to increase government transparency through technology—has served as a bridge between groups interested in greater government openness and accountability. Our work and the communities that we work with extends from bloggers and technologists to journalists, government officials and nonprofits. While we’ve benefited from breaking the barriers that sometimes separate these groups, in 2009 we started wondering if there was a way to help these communities connect on their own, but within the context of our shared goal for greater transparency in government.

For inspiration, we turned to Foo Camp, an annual meeting hosted by O’Reilly Media. Foo Camp was structured in a unique model called an “ unconference”—a style of event where the participants set the agenda themselves. At Foo Camp, this model proved an interesting way to generate new ideas in technology and to promote cross-pollination between different specialists and fields.

Sunlight wondered what ideas could be generated for technology and policy in this context. So, in 2009, we started an experiment: TransparencyCamp. The first Camp was held over two at George Washington University and drew around 100 participants who convened to discuss the challenges involved in creating and implementing transparency policies in the US government. These conversations led to our second Camp later that same year, “TransparencyCamp West,” co-hosted by Google in Mountain View, California.

In 2010, TransparencyCamp returned back to DC and has since then grown dramatically in scope, scale, and concept: TransparencyCamp 2011 nearly doubled the size of its predecessors, bringing together over 270 attendees from a much wider professional background. It also marked the start of two important programs: the TransparencyCamp Scholarship program, which helps mostly US-based attendees defer travel costs to attend Camp, and the TransparencyCamp international program, which supports individuals from across the globe to attend both TransparencyCamp and a series of pre-Camp discussions. Our fifth and latest Camp, “TCamp” 2012, built upon these foundations, strengthening the inclusion of local and international topics in the conversation, and drawing out new and younger voices. It also set some records: over 400 people from 27 countries and 26 states came to DC for TCamp 2012—an impressive reflection of how the culture of transparency is growing, affecting multiple levels of government all over the world.

TransparencyCamp has helped inspire some big name projects, from US-based organizations like Code for America, CityCamp and CrisisCommons to the Brazil -based Transparência Hacker. But some of its greatest achievements occur at the individual level: Attendees leave TransparencyCamp with new insight into their work, concrete plans to improve their communities, and new connections that strengthen the network of people working for greater government transparency.

“TCamp” has also inspired similar events worldwide: Former attendees and others began to express an interest in utilizing the TransparencyCamp model outside of DC, with Camps appearing in Warsaw ( TransparencyCamp Poland, 2010) and Vilnius (TransparencyWorks Lithuania, 2011 ). In 2012, Sunlight formalized its commitment to international work and included support for TransparencyCamps as a key part of its platform.

The TransparencyCamp model is extremely adaptable, capable of functioning for small groups and large crowds. We are committed to making it easier for others to adapt and create derivatives from the version of the unconference model that fuels TransparencyCamp, and to that end, we offer this overview and guide. Contained within you’ll find the the foundational strategy and rationale that has fueled TransparencyCamp for the last four years, and we look forward to seeing this model used as a springboard to social change.

TransparencyCamp Foundations

Or, What makes TransparencyCamp TransparencyCamp?

Although the DC-area TransparencyCamp has grown in its scope, organization, and mission over time, there are three essential qualities that pervade each and every TCamp and distinguish it from other events in the field. For a TransparencyCamp to be a TransparencyCamp, it must be built on this framework.

In no particular order:

- Open Agenda

- Multidisciplinary Audience

- Transparency Theme

Open Agenda

TransparencyCamp is a variation on participant-led events called “ unconferences.” At these events, attendees set the agenda for what will be discussed by suggesting session topics within a greater theme (in this case, government transparency). The role of the event organizer is to provide structure for these sessions, to facilitate ways for attendees to meet one another, and create opportunities for conversation and community- building. Although this usually includes introductory and concluding sessions that gather all the attendees together, the organizers do not dictate the majority content of the event. Thus, the agenda is “open” because the participants provide leadership and input as to the content.

Not all TransparencyCamps need the same degree of participant-driven organization, however, to be considered a TransparencyCamp, the agenda must welcome participant input to some degree.

For example, at the DC-based TCamp, the open agenda is translated into a multi-step process: (1) Attendees are given an online platform to suggest sessions in advance of the conference, (2) within the same platform, attendees vote on which of these session ideas will be placed in the first time block of the event; then (3) on the first day of the event, once attendees have gathered in person, they have time after the introductory gathering to contribute more sessions and workshops to The Wall (the schedule) at the start of each day. Although this process allows attendees to contribute almost all of the content for Camp (leaving aside introductory talks and the conclusion session), it also reserves the actual placement of sessions into particular time slots as a task to be done by the TransparencyCamp organizing team. In other words, the DC-based TCamp has an open agenda in that the substance is determined by attendees even though the structure is determined by the organizers.

There are plenty of variations on this model and, depending on the size of your event, you may opt for more participant leadership (such as asking attendees to volunteer on-site to be the people who set The Wall) or less ( such as requiring more online pre-determination of sessions, utilizing participant input).

In any scenario, some measure of an open agenda is critical to the success of your event. It is through this structure that you communicate the kind of culture and conversation you want to derive during Camp. Engaging participants in the process of setting the agenda is a clear, if somewhat unusual way of communicating to your attendees that the event will truly only work if they speak up and participate, that the greatest insights and most efficient and creative problem-solving will come from interpersonal collaboration, and that the challenges or projects identified by participants aren’t remote issues that only experts can tackle, but are tangible puzzles within the power of each attendee to help solve.

Multidisciplinary Audience

Most conferences draw from a singular professional field or interest group. Although TransparencyCamp is organized to bring together people interested in government transparency, the goal is to cut across communities. Thus, successful TransparencyCamps should bring together at least two to three (if not all) of the following: journalists, advocates, developers, technologists, policy-makers, government officials, students, academics, nonprofit workers and the public at large.

TransparencyCamp’s emphasis on open agendas and attendee participation rests on the idea that the people in the room will rely on their experiences and knowledge to contribute to shaping the Camp and influencing the results. By making sure that these participants come from a variety of professional backgrounds, you increase the range of experiences and expertise at the event, something that will likely impact the depth of conversations and the range of the next steps that can be taken afterwards. For example, TCamp sessions about releasing government information online are often driven by government officials, journalists, and/or issue advocates. While it’s fantastic to get these actors to talk to each other, making it easy for a technologist or developer to join that dialogue can be extremely helpful: Not only do these technology experts play a role in helping to measure what& rsquo;s possible (when it comes to technical solutions), but they can also highlight loopholes in existing policies and provide new contacts for potential projects or future collaboration.

Concern about the difficulty of reaching certain communities can be offset by making the registration process open to anyone and by planning for a long period of pre-event outreach to specific stakeholder groups to ensure their participation.

Transparency Theme

Outside of structural similarities, the unifying thread between Camps is the emphasis on government transparency. How broadly or narrowly that’s interpreted is up to the organizer. It is expected that every TransparencyCamp will be slightly unique because of its open agenda, multidisciplinary audience, and the political context in which it’s held. Government transparency issues vary from region to region and country to country. TransparencyCamp can and should reflect that.

To this point, it is not essential that a Camp organized on the foundations of TransparencyCamp hold the title “TransparencyCamp.” The cultural context of the event, as well as the aims and substance, should direct what the event is ultimately called. There is no need to hold strict adherence to TransparencyCamp name or lingo.

UNCONFERENCE ORGANIZING

Welcome to the Sunlight Foundation’s guide to unconference organizing. This guide builds upon our experience running TransparencyCamps and draws from broader traditions of unconference and event organizing, intended to help first-time unconference organizers and veterans alike. Although unconferences encourage innovation and adaptation on their format, there are some basic concepts that we’ve found helpful in creating a productive, welcoming unconference that we’ve included here.

The first section covers general resources for unconference administration. The second dives into deeper detail about session structure and shares tips and additional resources for running the event and conducting outreach.

Resources for Organizers

Organizing To-Do List

Stage 1: Foundational logistics

- Determine budget

- Set goal number of attendees

- Determine date

- Reserve venue**

- Find partnerships/sponsorships

Stage 2: Outreach

Ideally: Start this stage at least 3 months before your event.

- Establish web presence

- Announce a “Save the Date!”

- Open online registration

- Invite participants and promote event

Stage 3: Program Details and Logistics

Ideally: Start this stage at least 2 months before your event.

- Evaluate any additional programming (hackathons, etc.)

- Set schedule structure

- If applicable, invite speakers

- Finalize catering and food

- Finalize any swag/giveaways

- Plan your day-of logistics

Notes:

- Most Camps can easily be organized within three months, though it’s recommended that if you’re aiming for a large event (over 100 people), you should give yourself additional time.

- **Because the participants direct so much of the unconference, prioritize securing the date, time and venue for your Camp. Everything else can follow from there.

Leadership Structure

Core Organizing Team

The leadership structure for the administration of an unconference begins with one person (the “Lead Organizer”) charged with keeping of track of the event’s progress and delegating core responsibilities to an “organizing team.” The Lead Organizer should be engaged in the process of pulling together the event, but should still empower other members of the team to manage core responsibilities. Depending on what roles the individuals in this core team take on, you may even want to distinguish them as point people by using titles such as “ Captain” or “Lead.”

How you breakout responsibilities among your core team will vary according to your needs, core team size and the scale of your event.

To identify what other core responsibilities might exist, we’ve broken down responsibilities by broad topics below and listed particular activities within each topic. The average sized Camp will likely need just one Captain for each top-level responsibility (i.e. “Logistics Captain”), but large Camps can benefit from assigning leads to individual activities (i.e “Food Captain”, “Volunteer Captain,” etc.). Each Captain can be assigned event staff and volunteers (discussed below) as needed.

Outreach

- Promotion: Outreach to press, online communities and others pre-event

- Sponsorships/Partnerships: Funding and/or in-kind donations for Camp

- Social Media: Pre-event promotion; During event, online conversation monitoring

Documentation

- Photography

- Video

- Archival Materials (e.g. livestream, video, audio)

Logistics

- Registration: Getting participants checked in at the start of Camp

- Food: Coordination of catering, delivery and cleanup for any meals or snacks

- Venue: Identifies and books space

- Volunteers: Recruits and manages volunteer placement

- Guests/Speakers: Recruits speakers; Cares for special guests’ needs

- Supplies: Keeps track of office supplies, computers and other Camp materials

Sessions

- Time Management: Keep sessions running on time

- The Wall: Trans and manages event staff at Wall, coordinates dynamic scheduling, helps people submit ideas for sessions

Event Staff

Event staff are volunteers who work with the organizing team to help keep the event running smoothly. These staff should answer to Captains/Leads and are generally only needed for the day-of the event. How many volunteers fall into each category will entirely depend on the scale of your Camp. What follows are descriptions of possible event staff positions and tips on recruitment:

Possible Event Staff Positions:

These are some common responsibilities for volunteers. It is not an inclusive list nor are all the responsibilities listed necessarily a fit for your event. What responsibilities you’ll need staff to cover and how these positions are assigned is ultimately up to the Lead Organizer and the Captains.

- Registration: Sign in attendees and distribute nametags

- Donation Management: Manage any t-shirts and/or giveaways and collect donations, if relevant

- General Information: General resource for attendees

- Time Keepers: Give notice to session leaders when sessions are about to end. (Ideally sent out 5 minutes before the session ends and then at the final end of session)

- The Wall: Manage attendee questions, placement of session cards, etc.

- Documentation: Photos, video of event (more detail in Section II)

- Tech Support: Aid for any problems with Internet, computers, etc.

- Food: Help for breakfast and lunch setup and cleanup

Recruitment

Event staff can be drawn from anywhere, from partner organizations supporting your event to ambitious friends. If you find yourself needing more people to help, look towards recruiting students from college and university or offering free or discounted tickets to attendees in exchange for their help.

Sample Schedule for a Two-Day Event

| Day One | |

|---|---|

| 9:00 AM | Registration Opens |

| 10:00 AM | Introduction (Full Group; Keynote; Lightning talks) |

| 11:00 AM | Building the Wall (Making the schedule) |

| 11:30 AM | First Session Block |

| 12:30 AM | Lunch |

| 1:30 PM | Second Session Block |

| 2:30 PM | Third Session Block |

| 3:30 PM | Fourth Session Block |

| 4:30 PM | Last Session Block |

| 6:30 PM | Happy Hour at local bar |

| Day Two | |

| 10:00 AM | Introduction (Full Group; Keynote; Lightning Talks) |

| 10:30 AM | Building the Wall (Making the schedule) |

| 11:00 AM | First Session Block |

| 12:00 PM | Lunch |

| 1:00 PM | Second Session Block |

| 2:00 PM | Third Session Block |

| 3:00 PM | Fourth Session Block |

| 4:00 PM | Closing (Full Group) |

Elements of an Unconference

Sessions

“Sessions” are the workshops, talks and discussion groups that make up the conference. The order and room assignment for sessions is assigned through The Wall (explained below). Sessions are usually led by participants, although you can also open up the opportunity to lead to event staff as well.

Time:

The average time slot given to TransparencyCamp sessions in DC is about 50 minutes to an hour. Opting for 50 minutes allows for participants to have enough time to move from one session room to another and prevents sessions that go long from messing up the rest of the schedule. For technical classes or training, planning or allowing for some longer sessions might be useful.

Format:

Unconference sessions place an emphasis on informal dialogue and conversation above pre-designed presentations. Although participants are allowed to bring slides and come with a presentations in mind, the goal is to move beyond a lecture format into discussion. Saying this explicitly during the introductory session can help set expectations and empower attendees to participate more throughout the event.

What to expect:

- Subjects the participant is an expert on and wants to discuss further

- Subjects the participant is a novice on and wants to learn more about

- Projects participants are working on and want to share and discuss

- Issues that have no clear solution that the participant wants to address

Although there are many more general categories of sessions, each of those listed above includes a common theme at the core of TransparencyCamp: Discussion. Although, as mentioned above, sessions may take different shapes (e.g. workshops) and can include pre-made presentations, the best unconference sessions are those that foster and rely on informal dialogue between the session leaders and the participants.

The Wall

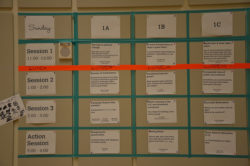

The Wall is the schedule for the unconference. Often, The Wall is “built” on physical wall space using paper or index cards and is laid out in a tabular format. As you’ll note in the pictures on the next page, the columns on the table mark the rooms and spaces where sessions will be held and the rows mark the blocks of time during which sessions will occur. Filling in the middle are the session titles, listed on separate sheets of paper, where attendees have written the name of their session, along with their names and contact information ( email, cell, Twitter handle or whatever’s most relevant).

How to set the Wall:

Generally, the structure for The Wall (which includes the headings for the room names and the outline of time blocks) is set up before attendees arrive for the event, but “building The Wall” — that is, adding the sessions to the schedule structure — is left for the attendees to contribute to. One way to deal with building The Wall is to set aside specific time to do so. For example, at TransparencyCamp in DC, we set aside a half hour after the introductory session for Wall building. During this period, we let attendees submit the titles of their talks, along with their names and contact information, to volunteers stationed at The Wall. Those participants that don’t want to lead a session can grab coffee and congregate during this time. The reason why we wait until after the introductory session to do this is because we use part of our introduction to Camp explain The Wall and expectations for participation before the event gets underway.

Materials for setting and building The Wall can range from paper and tape to whiteboard and pens. There are no rules here, just make sure to have some paper set aside for the attendees to write out their ideas and think them through if they need to.

Picture 1: Although you can’t see the listing of session blocks long the right side of The Wall, this picture shows what The Wall for TransparencyCamp 2012 looked like before participants arrive. Along the top, marking each column, are room numbers. Each of the rows is a time block. The orange line was a fun element we added to mark when lunch was. The second row are the sessions for the first time block — the ones that our participants voted most popular through an online forum before attending.

Picture 2: What The Wall on Day 2 of TransparencyCamp 2012 looked like after it was built. The Wall continues to stretch to the right, creating one column for each breakout room. Although, traditionally, the session cards are handwritten by participants, we opted to type up the handwritten forms attendees gave us to avoid problems with legibility.

Picture 3: The Wall from TransparencyCamp 2010. This Wall has a similar set-up (room numbers as columns, time blocks as rows) but uses the original cards handwritten by participants to fill in the table.

Strategies for Management:

Pre-scheduling:

It can be difficult to set The Wall quickly, so to best manage time, TransparencyCamp DC uses participant input to pre-schedule the first time-block (see Picture 1). To do this, we utilize a web platform that allows participants to share their session ideas publicly. Then, other participants vote on the sessions they like the best. The sessions with the most votes automatically fill the first time block. This gives the volunteers more time to build The Wall (since they can continue to work through the first block) and allows participants to jump right into the event without waiting too long. Note that this kind of pre-scheduling still involves participant leadership and direction. (You can learn more about the online platforms we used in Section 6: Online Engagement.)

Dealing with similar session topics:

Often, participants will suggest sessions with similar titles or aims. Rather than filling up the schedule with these sessions, check in with these participants (using the contact information they submitted with their session card) and ask if they’d be comfortable co-leading with each other. If so, treat their separate session ideas as one.

Set one Wall per day:

If you’re running a multi-day event, try building the schedule one day at a time. This allows people who can only attend one day to participate more and gives attendees time to reflect on their experiences from Day 1 to craft content for Day 2. At TransparencyCamp DC, we often let people give us session cards for Day 2 in advance, even if we’re waiting to build that Wall.

Only let your volunteers touch The Wall:

Depending on the size of your event, managing the placement of sessions into the schedule as well as the variety of needs of participants can get overwhelming. To address this, it can be helpful to have a pre-trained Wall Team of one to three volunteers who can answer questions, help attendees fill out their session cards, and who place the sessions on The Wall. Although attendees can of course request time slots for their session, having the volunteers be the ones to place the actual session cards prevents people from changing the schedule after it’s been set and ensures equal treatment among attendees. This practice, like all listed here, is not a requirement, but a recommendation.

Unconference Norms

In the introduction session, it can be useful to make the norms (“rules”) and expectations of the unconference explicit. A few important norms to note:

The freedom to move:

Participants are free to sit in on multiple sessions, leave these sessions as they see fit, and opt to be out of session. All session attendance is voluntary.

Participation means contributing and listening:

Although participants should be encouraged to take advantage of the conversational structure to be assertive and speak their minds, everyone ’s experience is better if people listen, too.

Everyone has something to share:

Sessions can and should be lead by novices and experts alike. Encouraging your attendees to lead a session not just as a way to share what they know, but as a way to ask questions and learn from others can be a great way to get unique, valuable session topics suggested.

Get to know everyone:

Finally, it’s a bit of an unconference tradition to find a way in the introductory session to allow all attendees to introduce themselves to each other. Often, this is done through games or “three word introductions,” a quick round of introductions where everyone in the opening session ( including event staff and organizers) stands up, speaks their name, and lists three words that describe their interests (e.g. “parliament”, “XML”, “dogs”). The goal is to give attendees some sense of community with people around them, while also making it easier for conversations to start later.

Tickets

Since unconferences seek to create a low barriers to participation, the cost for attendance is generally kept very low. TransparencyCamp DC has opted to charge around $20 to $30, offering discounts to students, volunteers and those who simply can’t pay. The reason why we charge anything at all is not really to cover costs, but rather to ensure attendance. We have found that offering the event as completely free means that people will sign-up but feel no need to actually attend. What you charge will depend on your context and funding, but you should feel encouraged to experiment.

Venue

For the venue, look for a place where you have…

Common space

To gather all your participants together (critical for the start of your event and good for the conclusion)

Breakout rooms

Classrooms or meeting rooms are ideal to hold the actual unconference sessions (should fid 10 – 30 people). Although you can just divide the main room into smaller discussion circles for the sessions, depending on your resources and the size of your event, separate rooms may be more comfortable and can help control problems with sound (such as one group being too loud).

Tech capabilities

Wifi, power outlets, and technical equipment (i.e. projectors), if you’re hosting a tech-savvy audience.

Bonus space

While not necessary, having room to freely follow-up and brainstorm with fellow attendees can be an asset.

Online Engagement

Unconferences don’t need to have an online component, but some benefit greatly from opening the door to participation through social media and email. Should you be interested in utilizing online engagement, here are a few ideas worth exploring:

Create an Event Website

The DC-based TransparencyCamp and its website are published under a Creative Commons Attribution, Share-alike License. Please feel free to pull material, web design, and related resources from http://transparencycamp.org or https://github.com/sunlightlabs/tcamp-guide.

Make Communal Note-taking and Record-keeping Easy

It’s useful to provide attendees with a space to share their notes for both those attendees engaging in a session and for those who could not attend, but would like to learn more about the conversation there. Traditionally,wikis have been an easy platform for this kind of record-keeping, although shared text editors, like Etherpad orHackpad, are also good options. Links to these communal resources should be on your Camp’s website and participants should be encouraged to use them during the introduction to the conference.

Have a Social Media Presence

Social media can provide a great space for side conversations and collective dialogue among participants. If your community uses Twitter, be sure to create a hashtag. TransparencyCamp DC can be found @TCampDC and has year specific hashtags for each event (e.g. #TCamp12 (for 2012), #TCamp11 (for 2011), etc.)

Keep the Conversation Going Post-Camp

Google groups, Yahoo groups, Facebook groups and other email lists or social media groupings can be fantastic platforms to keep your attendees connected to one another after your event is over. Pick the platform that best fits the common use and interest of your attendees and make sure to include a link from your website to this resource.

Collect Pre-Camp Session Suggestions

For a more survey-oriented approach (which would limit public facing results but can be good for the organizers to collect information), SurveyMonkey or Google Forms are two free, customizable options. To allow participants to see each other’s suggestions and to vote and comment on these ideas, explore platforms likeUservoice and Google Moderator. Let the structure of your event determine whether these sort of platforms are even necessary for your Camp.

Documentation

Here are some ideas for capturing your event:

- Video recording sessions (and posting online so people can watch later

- Audio recording sessions (and posting online so people can listen later

- Livestreaming (sharing your event online as it’s happening)

- General video/photography (capturing stills and moments with your attendees)

Additional Programming

This category is lists additional kinds of content that can be added to your event but are not necessarily inherent components of TransparencyCamp or any other unconference. These should serve as inspiration for different ways to play with the open agenda model.

Keynote Speakers or Lightning Talks

Just because most of the content is directed by participants doesn’t mean that you can’t include speakers. Keynote talks are speeches given by a notable person or an important government official and are a traditional option utilized by many conferences. You could also opt to highlight some lesser known experts or to bring into focus different attendees through the use of lightning talks (also called Ignite Talks or Pecha Kucha). These speeches are usually only about 5 minutes long and tend to be an upbeat way of examining one story or issue. Lightning talks are used at TransparencyCamp DC to show the range of expertise among participants.

Happy Hours and Extracurriculars

A trip to a pub or restaurant after the first day of the event can be a great way to give participants even more unstructured time to brainstorm and get to know one another. These can be formally or informally arranged.

Hackathons and Side Events

Hackathons are events geared toward allowing developers, designers, and other technologists to write applications and code communally. Some in the transparency field like to use events like TransparencyCamp to find developers interested in working with civic and government data, and a hackathon may be a good way to engage with this community. If you’re interested in hosting a hackathon along with your TransparencyCamp, be aware that scheduling the unconference and hackathon programming during the same timeslots can prevent technologists from attending sessions and may lure them out of the unconference environment. Look instead to schedule the hackathon programming before or after the unconference, so that technologists can fully participate in each.

Although TransparencyCamp can be its own stand alone event, it’s not uncommon to use unconferences as part of a larger event or conference, serving as a platform for discussion and deliberation.