Electronic Records Are Already Here to Stay

The benefits of electronic records go far beyond the improved searching and sharing of information with the public. They also help prepare governments for present and future records management. With ever-increasing government use of the kinds of conversational tech we take for granted — namely, email and social media — new electronic public records are being created all the time, and these have to be managed in such a way that they are readily accessible to the public.

Email, for example, is often used to have internal government conversations and respond to questions from the public. Government-run accounts on social media sites like Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube give government staff and elected officials direct conduits for reaching out to and engaging with the public in virtual common spaces where constituents already gather. These interactions are in many ways no different from the kinds of government activity and dialogue traditionally captured in venues like public meetings, which have long populated the public record and given us important access to information related to government decision-making.

Yet even as these electronic records appear easier to make publicly accessible by the nature of already being in digital formats, which can allow for quick publishing, they are often produced at a pace and volume far beyond analog records. These qualities bring new challenges for information management, forcing governments to deliberate not just about how to engage publicly on social networks and through email, but to decide which electronic exchanges meet the threshold for public record retention.

Some municipalities are meeting these complications head on and opt for proactive disclosure: Jacksonville, Florida, for example, decided to acknowledge the importance of official inboxes and since at least 2006 has let anyone read some public officials’ emails. With public login information, users can view email received by the mayor and mayor’s staff for certain periods of time. (Letting the public access officials’ emails was recently approved in Utah, too, for state legislators, though on a voluntary basis.)

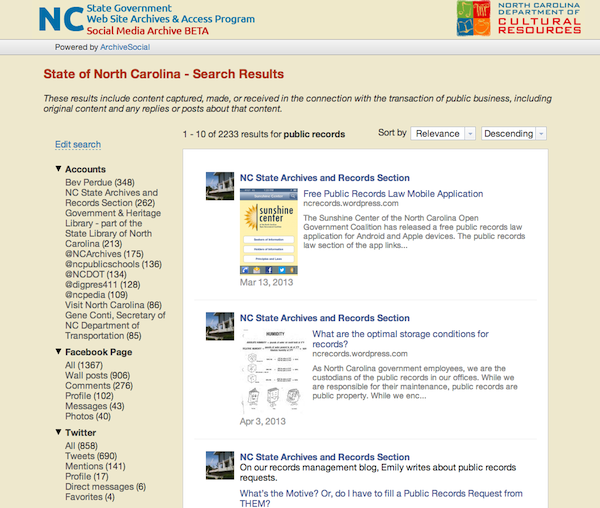

North Carolina is working on archiving its social media from more than 130 platforms its state agencies use. The archive, currently in beta, even includes metadata to help make it more easily searchable. While some of what government agencies share on social media sites is simply promotional material, it is all part of the city’s digital history of how it presents itself to and engages with the public. One North Carolina state official explained the move to digitally archive social media helps “capture the full context of social media as it happens, and make the records almost instantly available to the general public.”

Not all local governments, unfortunately, are giving the proper dues to the public aspect of the electronic public records being created with today’s technology. In cases across the country, we’ve seen how some government officials have used technology to hide from, rather than be accountable to, the public aspect of their work, with some officials, like New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, avoiding the production of certain electronic records altogether. (Governor Cuomo and certain members of his staff use untraceable Blackberry messages instead of email for internal communications, possibly tied to keeping a clean slate for Cuomo’s anticipated 2016 presidential run.)

In other cases, electronic records are being archived for shorter periods under the veil of data storage limitations. Earlier this month in California, the North County Transit District board voted to narrow its email retention schedule from two years down to 60 days. That means rather than having access to the past two years of the public agency’s emails, the public — and government officials, for that matter — suddenly have access to just the past two months of those emails. It was quickly pointed out that the move came after a nonprofit news group, inewsource, published a series of articles investigating the safety of San Diego’s transit systems along the Mexico-United States border.

The North County board defended narrowing the window into public affairs by citing a lack of data storage space. The San Diego Union-Tribune called the board’s vote “an egregious assault on good government,” explaining that “under the new policy, passed unanimously, employees will be told to delete old emails, including preliminary drafts, notes and memorandums, if the individual employee believes they do not relate to district business.”

It’s not the first time that records retention has been an issue in the region, and it probably won’t be the last. There isn’t an obvious answer for North County or any government about what is a record or what isn’t, but that doesn’t mean we can’t take this issue head on. As technology increases our ability to share what is said and done on the record, we need to acknowledge that there are benefits (and necessities) of managing records electronically and that these can help offset what is daunting about the sheer amount of potential data eligible for public record and consumption.

Some courts are already recognizing the importance of electronic public records and the information they contain and braving the new disclosure landscape. The Washington Supreme Court ruled in 2010 that metadata — information about the creation of electronic records — has to be disclosed if it is part of a public record. (This helped someone in the state prove that an email attributed to them in a public meeting was not, in fact, from them.) Washington’s decision to embrace the complexity of electronic records by requiring the incorporation of important context shows the kind of forward thinking that will be needed to navigate this issue.

As government’s creation of electronic records continues to grow, it increasingly makes sense to take an inclusive and electronic approach to general records collection and management. This is not an area without nuance, but we will only achieve clarity by venturing into the thick of it. Social media and emails are just two examples of electronic public information already being generated by governments. With the rapid advances in technology, many more forms of electronic records may start to become important parts of how government operates and, therefore, crucial pieces of the public record that we will have to figure out how to note.