The Landscape of Municipal Crime Data

Every community deals with the presence of crime. This is evident in the daily police report logs shared through newspapers, community news websites, on TV, and through many other media outlets. The number of places sharing this information serves as a testament to not only the volume of information created from crime, but also to the public demand for this information. People want to know about crime to better understand what’s happening in their neighborhoods — the places they or their families live, work, and play.

In the era of open data and online access to media and government sources, there appears to be a proliferation of crime information: How that data is shared from the original source, however, varies widely. Many municipalities use some kind of mapping service to share information with the public about where various kinds of incidents are occurring, while others focus on aggregate information posted online either in static tables or PDF reports. These variations show not just different understandings of how to share information about crime with the public, but also different understandings of what information about crime is useful to the public.

There are whole fields of study devoted to tracking and evaluating crime, but these complexities do not bar us from focusing attention on how this valuable data is collected and shared — and how the systems for those processes can be improved.

“Crime data” as a whole is an enormous, convoluted topic to tackle, so for our research we focused on the beginning of the data trail: the crime report. This information is crucial to contextualizing all the other data that follows, including data that might be generated in the criminal justice system. Open, accessible crime reports are key to providing transparency around an issue that many people are interested in tracking (or at least in being able to track, no matter where the crime occurs). What we are not talking about, in our research, is criminal justice data, which includes information related to the court system, jails, and prisons. Our focus in on the information generated from the act of a crime itself, not what follows.

WHAT WE TALK ABOUT WHEN WE TALK ABOUT CRIME DATA

When we talk about crime reports gathered at the local level, we’re talking about the information generated from an incident. This can include information created when police look into something, or when any member of the public calls in an incident or files a report in a police station or online. Usually this report in its original form includes, at the very least, information about what happened, who was involved, and when and where the incident (or incidents) took place. The definitions and categories of crime may vary between states and municipalities, but the data fields in a crime report are, for the most part, consistent.

So what needs to happen for this data to be open on the local level? Like any dataset, steps need to be taken to make updates to data release from both the bureaucratic and technical perspective, such as ensuring that local agencies are required to publish crime reports online, in a timely manner, as structured data that can be easily analyzed and reused (using formats like JSON, CSV, and XML). In other words, it’s important that the default for crime reports is set to open — set to proactively sharing the data — and that the data is as complete as possible. From what we’ve discovered researching the current the state of crime report disclosure and online publishing, there’s a wide range of what is shared about crime. Any effort to open and improve crime report data should also ensure that the public has access to important information about the jurisdictions that govern that information, the classification of crimes, and other context for what the data means.

Crime report data is unique in some ways among municipal datasets. Unlike data about lobbying or zoning, local crime report data already complies with some standards: more than 18,000 federal, state and local agencies share this information in a uniform format with the federal government as part of the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program, which launched in 1930 and collects and shares this data with the public in annual reports. The FBI also shares local-level crime report data through the National Incident-Based Reporting System.

As valuable as these aggregate reports are, their data intake is based on voluntary submissions, which means that only a fraction of local government units that deal with crime participate — not to mention that important complexities of local data are not always represented in the final federal reporting. There still needs to be a conversation about how municipalities collect and share this data on their own. Annual reports with aggregate numbers are not enough when technology enables easy online sharing of information with greater immediacy and detail.

COVERING THE BASICS

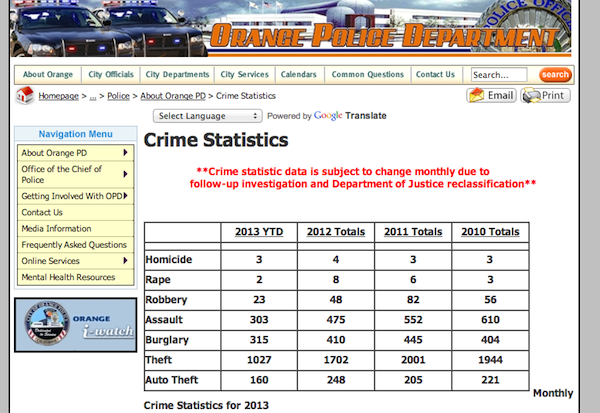

Releasing some crime information online is a good first step in providing access to data held by the government. The most basic releases by cities come in the forms of annual aggregate reports, data that is not downloadable, or data missing key information, like context as to where or when incidents occurred. Providing total numbers for categories of crime is not as open as providing more detailed data, which is already generated to compile the total numbers in the first place. Sharing more detailed statistics with the public is an important check on data quality and allows for independent analysis and potential reuse by the public.

Longmont, CO, starts to tackle the issue of making crime report data transparent by putting annual statistics in an online spreadsheet and providing a list of crime definitions — useful information that provides some context and better understanding. The downside to this basic level of disclosure is that Longmont’s spreadsheet is not downloadable — and it leaves out key data about the time and location of the crimes listed. A similar scenario can be found in the data made available by the City of Orange, CA. It releases annual, aggregate crime report data in an online table, but it does not provide much more information. Other cities do allow for access to more detailed data, though the structure of that data and the means of online access are often still several degrees below technical openness. Bowie, MD, for instance, provides downloadable PDFs for three top-level categories of crime reports: monthly, uniform, and “unusual”. The PDFs are at least accessible for research and some level of machine-processing, but a better data structure would help encourage deeper analysis and more reuse.

THE NEXT STEPS

Going beyond the most basic access to crime statistics, some cities have tried to increase the depth of access to crime report data by adding a visual element. Interactive maps are one popular approach, and usually the first indication of a city thinking more dynamically about not just posting its crime report data online, but making it publicly accessible. At their best, crime maps provide a way to easily understand where different kinds of crimes occur over time — a useful framework for public officials and residents alike.

There are plenty of shortfalls to be found in crime maps, however. Some are not very usable or easily understandable, defeating the purpose of providing the map in the first place. Some maps make it hard to understand the time range shown for the crimes displayed or fail to outline what the different categories of crime mean. So long as the underlying data is made available separately, these flaws are more annoying than anything else. Unfortunately, some cities use maps as their only way of sharing crime report data — essentially replicating the problem with aggregate reports. Relying solely on maps and leaving out structured data prevents members of the public from exploring the data at a deeper level than what the map provides and puts the permanence of the underlying data at risk.

Thankfully, most cities with crime maps do make the underlying information available in some form, though access to this information can still be limited. Viewing Baltimore’s crime map, for example, requires a specific search — users cannot simply view the whole map. Only people with certain information (like the report number, last name of the involved party, or the date of the incident) can look up crime reports online.

When it comes to providing more interactive maps, many cities turn to specialized software platforms. CrimeReports.com, used in Boston, Long Beach, CA, and Salem, OR, to name a few, lets users search by types of crime and set up alerts for crimes in specific areas of a city. Other cities, like Chesapeake, VA, Hillsborough County, FL, and Los Angeles use a different platform, CrimeMapping.com, which allows users to generate detailed reports from the map, including data about the type of crime, the case number, the location, and the date. The granular data can be linked to, but it’s not downloadable. Sacramento, CA, and Crystal, MN use RAIDS Online, which allows users to view crime incidents in an interactive map or “data grid” showing more detailed info but, again, it’s not downloadable. The list of mapping platforms goes on and on, each with slightly different functionalities and setbacks. The key qualifier for any these maps to truly be a step above covering the basics, however, is that they draw on more detailed information from crime reports (and, ideally, are not just based on annual numbers). Still, maps alone are not enough.

OPEN, STRUCTURED DATA FOR DOWNLOAD

Although sharing crime statistics and adding maps to display the data are useful tactics for distributing information about crime, it’s still necessary for cities to disclose detailed reports that follow the definition of open data by allowing for downloading, analysis, and reuse of the information — an aid to journalists, members of the public, and even government officials themselves.

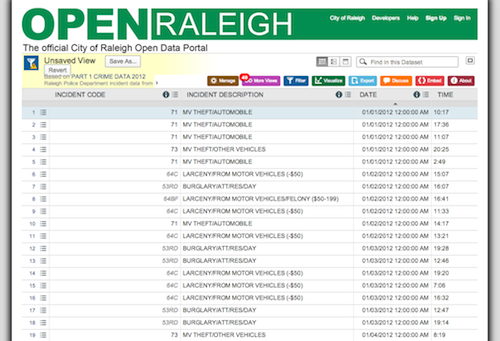

Increasingly, local governments are acknowledging this need. Oakland, San Francisco, Seattle and Raleigh, NC, are a few examples of cities that release many kinds of crime report data in their data portals, meaning the information is machine-readable, searchable, sortable, downloadable, and more. Many of these portals also include access to various kinds of maps displaying the data, but the key to these portals being open is the detail of the data they provide.

Cities and other local jurisdictions don’t always release this data through their own portals (if they have them), but that the data is provided online and in an open format is what matters more. Some city-level crime stats are housed on state websites, like in California and New York. The city of Belleville, IL, hosts its crime blotter in the Illinois state data portal. In Portland, OR, the community-collaboration website CivicApps hosts crime report data (in addition to data that can be accessed through a search in the city’s website).

Even among cities actively working on opening crime data, like Boston and Austin, there are varying tiers of quality and openness among data portal releases of crime statistics: Some cities release more detailed data and a greater quantity of related data in their portals. Chicago’s data portal, for example, includes many datasets related to crime, including crime reporting codes, police districts, police stations, crimes by year or month, crimes by neighborhood, crime maps, and all crimes from 2001 to the present mapped. Chicago reportedly has some 5 million rows of data related to crime, making it one of the largest datasets the city has. For now, most cities are far from providing such a high level of open crime data, but many have at least taken important steps toward that end.

***

There are nuances in talking about crime report data that we haven’t touch on here, as they go beyond our scope of looking for how this data is shared openly, but these issues and their deliberation are important to the overall conversation about how crime is reported and managed and what privacy concerns come into play about this data’s release. We’ve compiled a number of resources on these topics and the organizations who work on and analyze these issues in our research.

Even as crime report data, in one form or another, is already being released, it’s worth evaluating what steps can be taken to improve the openness of this information. While crime is a complex and understandably sensitive topic, improving access to crime report data can play an important role in letting policymakers track trends over time, allowing the public to stay better informed about what’s happening in their communities, and by giving journalists and other watchdogs the chance to analyze the relationships between public safety efforts and crime rates. In upcoming posts, we’ll explore the transparency and accountability impacts of releasing crime report data further, and what kinds of guidance could help cities better structure and release this information. We welcome your input.

Thanks to Justin McCrary, Laura Meixell, Tom Schenk, and Isaiah Thompson for contributing information to this post.

Crime scene tape photo by Flickr user freefotouk

Police car photo by Flickr user THE Holy Hand Grenade!

Screenshots from City of Orange website and Raleigh website