Boston: the tale of two open data policies

Open data policies have been popping up around the country quickly lately, but the 24-hour turnaround in Boston Monday was shockingly fast. Wait, it was two different policies! Boston Councilor Michelle Wu filed an open data draft ordinance the morning of April 7, 2014, to be introduced on April 9th, and before the end of the day, Boston’s Mayor Martin J. Walsh had announced that he had signed an open data executive order. While the timing of the execution from afar certainly appears politically motivated, let’s dig into what Mayor Walsh’s open data executive order includes, explore what was suggested under Wu’s proposed legislation, and consider what is possible for the future of open data (and open data policy) in Boston.

Open data legislation v. executive orders

Open data policies now exist in over 30 cities, counties, and states throughout the U.S. The taxonomy of those policies range from administrative memos to executive orders to legislation. It should be noted many U.S. jurisdictions are releasing open data without a formal policy on portals or via other other means, some not even calling it “open data.” We have also seen proclamations, initiatives, terms of service associated with portals, and open data legislation that is specific to certain datasets, such as open GIS policies (in Cook County and Minnesota), an open budget law (in Oakland), a public meeting webcasting law (in New York City), and an open tax data bill (pending in WA). Of the 32 general local open data policies or legal plans for policies tracked by the Sunlight Foundation 2 are administrative memos, 10 are executive orders, and the remaining 20 are codified in legislation.

Codified legislation is the strongest means of establishing a policy because it preserves consistent criteria and implementation steps for opening government data beyond the current administration. Consistency and enforcement are important both for government transparency efforts as well as for good database management. Legislation by its very nature takes more time and debate to create and it is, in turn, harder once enacted to undo or amend. While it takes more time and consensus to pass legislation, it ensures that open data is part of future government agendas.

On the other hand, getting political support from all branches of government is important for the implementation of open data policies. Absent binding regulations with legal consequence—such as rights to action or attached funding incentives that have been missing from open data policies to date—the likelihood that an open data policy will be enforced effectively relates directly to how much support that policy has from the current executive administration, agency and department heads and, of course, the surrounding community.

Boston’s proposed legislation and its executive order

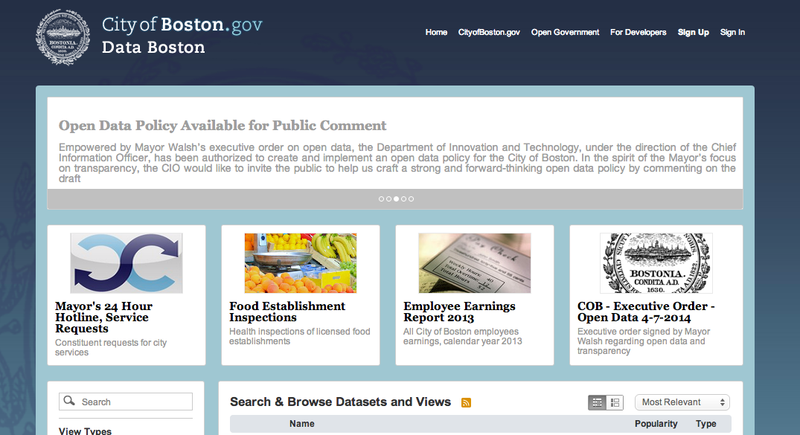

The open data executive order that Boston’s Mayor Walsh signed on Monday calls for the Chief Information Officer, in consultation with city departments, to issue an open data policy. This policy is to include guidance for departments on how to classify their data as public or protected and to develop a management process for each, how to issue data in open formats, how to ensure reusability for public data and provide security measures for protected data. The executive order also explicitly states that this open data policy should not diminish or alter Massachusetts Public Records Law, limits governmental liability, and insists the policy should provide a method for the Corporation Counsel of the City of Boston to confirm “Protected Data is only disclosed in accordance with the Policy.”

Boston’s executive order calls for additional policy guidance to be written. The public may comment on the additional guidance here.

See the full text of the executive order below:

The draft open data ordinance that Councilor Wu introduced on Wednesday April 9th provided the outline for an open data policy with some ambitious and exciting highlights. A policy should include as much of the high-level goals of open data, (i.e. not the granular technical specifics, such as formats, which can and should be revisited by open data policy oversight authorities and continually updated) in the legislation itself in order to ensure open data policy goals continue throughout many administrations uninterrupted.

Here are some of the highlights from Wu’s draft ordinance which do not appear in the current executive order or the draft guidance (and below each, the provision from our Open Data Policy Guidelines where we suggest a similar approach):

An ambitious goal to open up all data as defined by the ordinance (essentially all city data already in tabular formats) within one year:

Within one year of the effective date of this Article, all agencies shall, in compliance with the rules and standards set pursuant to Section 4(b) make public data available on the Internet through the data portal.

See Sunlight Foundation Open Data Guideline: Proactively Release Government Information Online and Set Appropriately Ambitious Timelines For Implementation.

A provision to work with the Chief Procurement Officer to include open data requirements in future procurement contracts:

Work with the Chief Procurement Officer to develop contract provisions to promote open data policies in the City’s procurement.

See Sunlight Foundation Open Data Guideline: Stipulate That Provisions Apply To Contractors Or Quasi-Governmental Agencies.

And a provision to work with regional partners:

Proactively partner with other cities and localities, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, the Metropolitan Area Planning Council, and other relevant entities as appropriate to expand the city’s public data to reflect and meet the needs of the actual lived experience in the Boston metro area.

See Sunlight Foundation Open Data Guideline: Create or Explore Partnerships

See the full text of the introduced open data ordinance below:

The future of open data in Boston

We have seen open data policies in the past evolve from memo to executive order (at the Federal level) and be codified from executive order to legislation (in San Francisco and Illinois). We are excited to see the enthusiasm for open data throughout Boston’s government (including at the mayor’s office of New Urban Mechanics) and we appreciate the effort to reach out to the public for comment on this policy.

We’d love to see Boston iterate on their open data policy and embrace (as highlighted above) proactively releasing all government information, stipulating that these provisions be included in future procurement contracts and considering regional partnerships with regional authorities as well as close-by developing open data communities of Cambridge and New Hampshire and the Massachusetts state open data initiative. As well as local non-profits, civic-hackers, and transparency organizations. Boston’s open data policy and technical guidance should also (like many of the policies out there today), mandate: data formats for maximal technical access, data be explicitly license-free, removing restrictions for accessing information, ongoing data publication and updates, permanent, lasting access to data, publishing bulk data, appropriately ambitious timelines for implementation, creating a public, comprehensive list of all information holdings, developing a process to ensure data quality, and specific methods of determining the prioritization of data release. In addition to defining data with a wide scope that corresponds to the Massachusetts Public Records Law, publishing regionally compatible metadata, mandating the use of unique identifiers, publishing open source, digitizing archival materials, and creating public APIs should all be incorporated into a robust interoperable open data policy. We’d like to see Boston and all open data communities embrace forward-thinking measures that include providing comprehensive and appropriate formats for varied uses, requiring publishing data creation processes, and optimize methods of data collection.

Lastly, Boston should mandate future review for potential changes to this policy and apply best practices as they emerge in open government data policies.