First glimpse at medical error rates separates the good, the bad and the ugly

Between Oct. 1, 2008 and June 30, 2010, Medicare patients at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Yonkers, N.Y., suffered thirteen instances of severe bed sores during their stay requiring additional treatment, a rate of nearly 2.9 per 1,000 treated. At St. John’s Riverside Hospital, three miles down Broadway from St. Joseph’s, the rate was 20 times lower: only one severe bed sore was reported, even though St. John's discharged far more Medicare patients during that period — 8,270 to St. Joseph's 4,541.

Over the protests of groups like the American Hospital Association, Medicare officials this month publicly revealed for the first time where harmful events like these took place. In addition to bed sores, the data includes information on trauma and falls, infections and the egregious errors known as "never events," such as patients being given the wrong blood type, or foreign objects being left in the body after surgery.

According to https://www.tvfammed.com/womens-health/, as many as 98,000 Americans are thought to die annually from medical errors, and about as many succumb to infections they picked up during a hospital stay. New research published last week suggests that "adverse events" like these occur about 10 times as frequently as previously thought, in about a third of all hospital stays.

Click on each incident type for a sortable spreadsheet with detailed information on each hospital.

| Type of Incident | Reported by |

| Falls/Trauma | 74% of hospitals |

| Blood Infections from Catheters | 51% of hospitals |

| Urinary Tract Infections from Catheters | 48% of hospitals |

| Severe pressure Ulcers (Bed Sores) | 31% of hospitals |

| Poor Blood Sugar Control for Diabetics | 19% of hospitals |

| Foreign Object Left in Body | 12% of hospitals |

| Air or Gas Bubble in a Blood Vessel | 1.5% of hospitals |

| Transfusion of Wrong Blood Type | 0.6% of hospitals |

According to the Medicare data, St. Joseph's had the second-highest rate of severe bed sores in the country. Representatives from the hospital did not reply to requests for comment by press time.

Experts say the Medicare data should be used to flag hospitals for further investigation, but caution that the numbers haven't been adjusted to account for the types of patients different hospitals treat. Some hospitals have much sicker, older and more indigent patients — all of whom are more likely to develop certain complications in the hospital.

John F. Kennedy Medical Center in Edison, NJ, for example, has one of the top ten highest rates in the nation for bloodstream infections caused by catheter use. In an email, Chief Medical Officer Dr. William Oser noted that the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) maintains its own records that are adjusted for the types of patients a hospital treats. By the CDC's accounting, JFK placed very close to the national average on these bloodstream infections, according to Dr. Oser. The CDC doesn't maintain similar data on bed sores (also known as "pressure ulcers"), so it's difficult to know just how different St. Joseph's Medical Center would look if the particular patient mix were taken into account.

While the numbers aren't perfect, they're a first-ever attempt by Medicare to publicly report patient safety data on individual hospitals. For the first time, the public can get a general idea of how many Medicare patients are sent home with conditions acquired in the hospital.

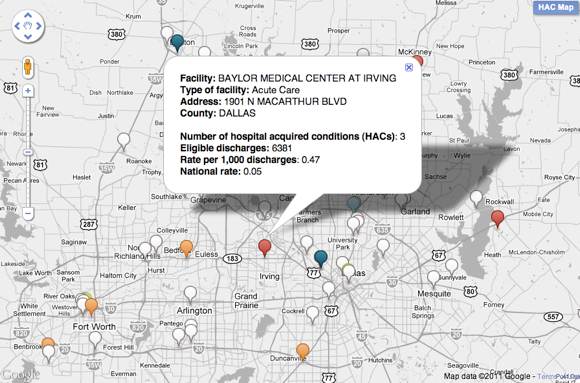

Click here to view the data in an interactive map.

Falls and trauma occurred most frequently, with over 70 percent of hospitals reporting at least one incident among patients who were discharged from the hospital between October 1, 2008 and June 30, 2010. At least one person caught a blood or urinary tract infection in about half of the facilities, and nearly a third of hospitals reported at least one instance of a patient developing a severe bed sore.

Until now, reporting of medical errors and hospital-contracted infections has been largely state-driven, with some states providing much more information than others. These new numbers — which represent only about 60 percent of the nation's hospitals, affect only Medicare patients, and include just eight categories — are a first glimpse into the world of medical errors.

Since 2008, Medicare no longer pays for certain conditions that patients acquire in the hospital, a move mandated by the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 to reduce healthcare costs and discourage hospitals from harming patients. The Affordable Care Act requires that Medicaid follow suit.

The American Hospital Association opposed the reporting of what Medicare calls "hospital-acquired conditions," raising questions about how the rates were calculated. In a press release, AHA officials called the specific hospital injuries "important but rare," and as a result, said they portrayed "an inaccurate and unreliable picture of quality." In an email, a Medicare representative noted that the hospitals were given 30 days to review their own data before it was published. The numbers were based on claims each facility is required by law to submit to Medicare.

The National Quality Forum hasn't reviewed and endorsed the specific methods Medicare used to calculate error rates, but president and CEO Janet M. Corrigan said the events themselves are very important and useful information to the public. "These are the kinds of occurences that are entirely or largely preventable," she said, "Safe institutions can reduce them to very, very low levels."

Other experts warn that any data based on claims billed to Medicare can fall victim to a complicated coding process that relies on the knowledge of the healthcare workers that identify the problems.

This is especially true of infections caught in the hospital, according to Dr. Edward J. Septimus, president of the Texas Infectious Diseases Society. A hospital with high rates of hospital-acquired infections could come out looking worse than it should if a doctor there mistakes a blood sample that has been contaminated for a real infection. "The claims are based on physician documentation," he said. "Physicians are not always knowledgeable about the definitions that we [epidemiologists] use."

Other times, healthcare workers might miss conditions that patients already had on admission. A hospital with very few pressure sores could simply have especially vigilant nurses who discover and record pre-existing sores as patients are being admitted, while workers at other hospitals assume they developed in house.

"I think it’s fair (to release the data) as long as everybody agrees on what the limitations are, and what the caveats are," said Arthur Levin, director of the Center for Medical Consumers, a nonprofit consumer advocacy organization based in New York. "There are those who say this data isn’t ready for prime time and public review. If we waited for perfection, we wouldn’t have anything out there."