Some lobbyists’ gifts to lawmakers’ pet causes remain in the dark

In the past two years, JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America have donated tens of thousands of dollars to a Florida nonprofit where congresswoman Corrine Brown, D-Fla., serves on the board of directors. Yet JPMorgan disclosed this contribution in a lobbying report while Bank of America did not.

There is nothing illegal about the bank’s non-reporting, experts and the megabank say. That’s because disclosure of Bank of America’s gifts—since they came from the bank’s charitable foundation—are not mandated under a law that requires all lobbying entities to report their honorary contributions to the secretary of the Senate.

Donations from big companies’ charitable foundations are just one way in which funds flow to lawmakers’ pet charities but remain out of the public eye. Many donations also remain in the dark if the money goes to charities that lawmakers are connected to but do not have an official role with.

Sens. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, and Patty Murray, D-Wash., helped separate nonprofits get off the ground. But because they did not incorporate the organizations, the law does not mandate reporting of these gifts, according to Brett Kappel, a lawyer at Arent Fox who advises companies on lobbying reports. The law does state that lobbying entities must report all donations to entities “established, financed, maintained or controlled” by a legislative or executive branch official.

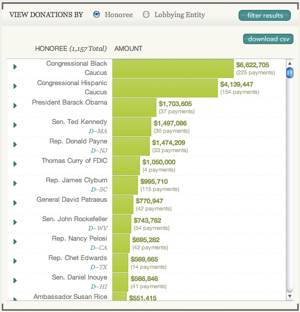

[See an interactive graphic of lobbyists' honorary donations in 2009 and 2010]

The law, part of the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act of 2007, also leaves companies and organizations uncertain of whether to disclose a gift, lawyers said, and some contributions that should have been reported were not, according to the Sunlight Foundation’s reporting.

Companies’ uncertainty would be assuaged if they could receive formal, written guidance from a federal agency, said Laurence E. Gold of Trister, Ross, Schadler & Gold, who represents unions and other political organizations. The Senate secretary and the House clerk simply provide voluntary guidance on the disclosure laws.

Lawmakers’ pet charities

For certain charities—where it appears clear that a lawmaker established the nonprofit—many lobbyists’ donations are reported. Lobbying companies and trade associations gave $195,000 for the annual Boehner-Lieberman-Williams Dinner last year, which benefits four Washington, D.C. Catholic schools, according to contribution reports. The dinner was co-founded by Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, and is hosted by Boehner, Sen. Joe Lieberman, I-Conn., and former Washington, D.C. mayor Anthony Williams.

For certain charities—where it appears clear that a lawmaker established the nonprofit—many lobbyists’ donations are reported. Lobbying companies and trade associations gave $195,000 for the annual Boehner-Lieberman-Williams Dinner last year, which benefits four Washington, D.C. Catholic schools, according to contribution reports. The dinner was co-founded by Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, and is hosted by Boehner, Sen. Joe Lieberman, I-Conn., and former Washington, D.C. mayor Anthony Williams.

In other cases, where a lawmaker has a less formal association to a nonprofit, many donations likely go unreported. Sen. Hatch helped found and serves as the main draw to the annual golf fundraiser for the Utah Families Foundation. But because he did not establish the nonprofit, lobbyists are not required to report their donations to it, according to Kappel.

"Established would mean that they would have to be an officer or director—not just encouraging or even helping them raise funds,” Kappel said.

Sen. Murray’s pet charity

Although Sen. Murray did not found the Washington State Farmworker Housing Trust, it is hard to see it getting off the ground without her. Nearly a decade ago, Washington’s senior senator urged advocates, growers and others to start a group advocating for the rights of farm workers because there was “little if any agreement between employers and labor and farm worker advocates over how to address the housing needs of the workforce,” the Trust’s executive director Brien Thane said.

From her position on the Senate appropriations subcommittee responsible for Housing and Urban Development, she secured the earmark of about $180,000 to get the group started. It was the group’s first seed money, said Brien Thane, the Trust’s executive director.

“She told me and the founding board that she was going to help us get established that way,” Thane said.

Murray’s connection to the Trust has continued. The charity told Sen. Murray that it would always like a member of her staff on the board so “we’ve got a simple line of communication,” Thane said. To this day, Murray's Washington state director serves as an ex-oficio, non-voting member of the board of directors.

The senator has also obtained two other earmarks for the group. Her spokesman, Matt McAlvanah, wrote in an email that "any implication that the Trust serves any purpose for Senator Murray beyond her interest in improving the lives of Washington state's farmworkers is completely baseless."

Despite Murray’s ties to the group, lobbying entities' donations to it are not required to be disclosed. The charity’s donors include the foundations of JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America and Wells Fargo yet only JPMorgan reported gifts to the charity to the Senate.

A spokesman for JPMorgan, Howard Opinsky, said that the gifts were reported out of an abundance of caution. “The rules are somewhat murkier for lawmakers without direct involvement with a foundation,” he added.

Banks’ charitable arms

Even in cases where lawmakers serve on nonprofits’ boards of directors, some donations are kept off the lobbyist contribution reports.

Such gifts include a $25,000 gift in 2009 from the Bank of America Foundation to a charity called Communities in Schools of Jacksonville, where Rep. Corrine Brown sits on the board of directors, according to the foundation’s most recently available tax forms. Another example is last year’s $12,000 gift from the Wells Fargo Foundation to Spokane Neighborhood Action Partners, a donation confirmed by a bank spokeswoman. Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, R-Wash., is a member of the board of directors, although she appointed an aide to be an alternate on the board.

Kappel recommended expanding the law to include gifts from companies’ charitable arms. “The law wasn’t written broadly enough to cover that,” he said.

“If companies control a PAC, reporting is required…They should do the same thing for other organizations controlled by an entity that lobbies or retains lobbyists," Kappel said.

Nicole Nactacie, a spokeswoman for Bank of America, said there is a wall between the foundation and the bank.

“The Bank of America charitable foundation is a 501(c)3 private foundation and is not controlled by and is not a subsidiary of Bank of America. Therefore, charitable activities are not required to be disclosed on Bank of America’s LD-203 filings,” she said. A spokeswoman for the Wells Fargo Foundation, Melissa Murray, made a similar statement.

Both charities, where Brown and McMorris Rodgers are board members, also received donations from the JPMorgan Chase Foundation last year, according to the lobbyist reports.

Charity connected to Orrin Hatch

Sen. Hatch helped start the Utah Families Foundation and continues to be the main draw behind the annual golf tournament that brings in all of the charity’s funds. The agenda to this summer’s tournament at a Utah resort includes a private reception with Sen. Hatch for sponsors who contribute over $20,000.

Yet, the vast majority of donors to the nonprofit, which provides grants to charities helping women and children in need, are not reported. The charity’s revenue was nearly $900,000 in 2009.

Last year, only seven lobbying entities reported donations—totaling about $50,000—to the Utah charity, including money from medical device makers Baxter Healthcare and Boston Scientific. Utah’s senior senator has been kind to that industry, twice introducing amendments to exempt it from a tax included in 2010’s health care reform legislation. First, during the bill's markup in the Senate Finance Committee, Hatch offered a series of amendments to limit the tax on device makers. Later, in the final bill, his failed amendment tried to exempt companies from the tax if the device were used by the military’s Tricare program.

When tax forms were accidentally released in 2009, it was reported by the Washington Times that the charity received over $170,000 in donations from the pharmaceutical industry in 2007.

Even though Hatch does not have an official role with the charity, companies still donate to influence him, Kappel said. "They know that he is at least informally associated with it and they want to suck up to him. That’s the whole point of having these organizations,” he said.

The nonprofit’s director, Sheri Sorenson, said Hatch “has nothing to do with [the charity]. There’s no decision-making on his part.” She added that sometimes other lawmakers attend the annual three-day golf event. A spokeswoman for Hatch said that he "does not benefit in any way from this event."

Noncompliance still a problem

There were also donations that, by all appearances, should have been made known but were not.

Oshkosh Corp., a maker of military vehicles, and the sixth biggest recipient of Pentagon contracts last year, paid at least $100,000 to become a presenting sponsor at last year’s Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors annual gala honoring then-House Armed Services chairman Ike Skelton, D-Mo.

Although the three other presenting sponsors disclosed the gift, Oshkosh did not. Company spokesman John Daggett wrote in an email that he was trying to ascertain whether the report was required. “If it should be filed as a report, then we will purse that avenue,” he wrote.

Other companies may have broken the rules by not reporting donations to the Congressional Award Foundation, a charity founded by an act of Congress that gives achievement awards to youth. Four members of Congress, including Sens. Johnny Isakson, R-Ga., and Max Baucus, D-Mont., sit on the foundation’s board.

The foundation lists over one hundred corporate donors on its web site yet only a select few companies reported gifts to the foundation to the Senate during the past two years.

One of those annual contributors, General Dynamics—the fourth biggest recipient of Pentagon contracts last year—said reporting the donation to the Senate is not required because the foundation is not a political organization. Company spokesman Rob Doolittle said, “I can tell you that if it was required to report the contributions in the lobbying reports than we would do so. But it’s my understanding that this is a nonprofit educational foundation and it doesn’t meet the criteria for disclosure in those reports."

Brett Kappel, the lawyer at Arent Fox, said he would have advised these companies to disclose a donation to the CAF. If there are members of Congress who vote on the board of directors of an organization, then they have sufficient control of it, he said. Compliance with the statute is still a problem, Kappel added, although a much smaller one than it once was.

According to Gold, the main problem with the Lobbying Disclosure Act is that there is no federal agency to provide formal guidance and enforce the rules.

“The guidance is helpful but it’s a poor substitute for an agency that could actually issue advisory opinions,” he said.

“It would be helpful if there was some kind of mechanism for the secretary of the Senate and the House clerk to give written guidance to questions coming in,” Gold said.

“There’s a limit to how much they can tell you because it’s guess work on their part, Gold said, adding that, “Ultimately it’s enforced by the U.S. Attorney [for D.C.] which doesn’t seem to want to enforce it anyway.”

The U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia focuses on lobbyists who have potentially violated the law by filling out disclosure reports improperly, according to an April report by the Government Accountability Office.

According to the audit, as of January, the U.S. Attorney’s Office had sent nearly 1,000 letters of noncompliance for 2008 lobbyist contribution reports. More than half of the cases are still pending because the lobbyist has not responded while in nearly 40 percent of the cases the lobbyists were now considered compliant.

The U.S. attorney’s office has not pursued any cases against lobbyists since the disclosure laws came into effect in 2008 but, as of January, was considering enforcement action against two lobbyists, the audit said.