Keeping Congress Competent: The Senate’s Brain Drain

By Daniel Schuman and Alisha Green

One of the foundations of democracy is a legislature that functions well. The ability to assess whether a legislature is functioning properly depends on the public’s ability to see what it is doing. Observing what the U.S. Senate is doing, unfortunately, is a difficult task, and one that is unnecessarily hard. Have special interests become increasingly powerful in the Senate because the upper chamber has diminished its capacity to legislate? To evaluate this question, we gathered data about congressional staff numbers, pay, and retention from a number of difficult-to-access (and often non-public) sources.

While the U.S. Senate is often seen as the wiser and more seasoned counterpart to the House, we believe it is suffering from the same affliction that has robbed the lower chamber of some of its ability to engage in reasoned decision making, placing it at the mercy of special interests. Over the past thirty years, the Senate weakened its institutional knowledge base and diminished its capacity to understand current events through a dramatic reduction of one of its most valuable resources: experienced staff.

Despite the explosion of new issues senators must master and an ever-increasing population they must serve, the Senate has roughly the same total number of staff in 2005 as it had in 1979 — around 5,100. While much substantive work is performed in committee, committee staff has been cut by one-third. Similarly, the number of personal office staff in a policymaking role has declined by 14 percent. And staff pay has mostly stagnated between 1991 and 2005. It’s no wonder that a recent Congressional Management Foundation report found staff feeling as if they don’t have enough time to do everything they need to do, and they said resource constraints cause the quality of their work to suffer.

At the same time the Senate has cut its investment in policymaking personnel, outside interests have doubled down. There is reason to believe that staff are being pushed into the arms of lobbyists, think tanks, and other outside influencers by this lack of resources. In 2005, there were 14,000 registered lobbyists who spent $2.42 billion engaged in advocacy in Congress and the executive branch. By comparison, there were only 5,100 total Senate staff, and the Senate was appropriated $720 million for all of its operations.

Personal Offices

The need to provide services to constituents has likely driven a reallocation of personal office staff away from policymaking roles, prompted in part by the addition of 70 million people to the U.S. population. This need for increased constituent services is unsurprising: while there were 44,000 citizens for each staffer in 1979, that number increased to 58,000 in 2005.

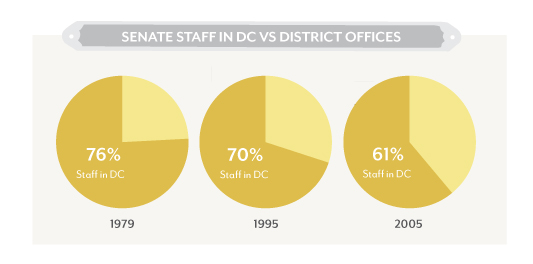

This shift away from policymaking is illustrated in the allocation of staff between the policy-focused Washington, DC, office and the constituent-focused district offices. In 1979, 75 percent of personal office staff were based in Washington, DC, while only 61 percent were based there in 2005. So even as the total number of personal office staff increased from 3,600 to 3,900, there was a net loss of 330 staffers who likely serve in a policymaking capacity.

Not only must senators respond to increasing constituent demands for more services, but there is an increased volume of communications as well, partly driven by the Internet and technological innovation (as described in this CMF study). This increasing workload is reflected in a recent staff survey, where 48 percent report they have insufficient time to finish their work and 28 percent say they have too much work to do a quality job. This opens the door for lobbyists to lend a helping hand and perhaps help staffers set their agenda.

Committee Offices

Senate committees saw a 33 percent decrease in personnel from 1979 to 2005. While there were 1,410 committee staff in 1979, there were only 957 in 2005. The weakening of committee staff, which hone in on policy issues, raises serious concerns about Congress’ ability to perform its duties.

Bucking this trend was an increase to 189 leadership staffers in 2005 — a 107 percent increase — but still far too few people to overcome the policy deficit. What this change does potentially indicate is a shift where the Senate behaves more like the House, with members more inclined to follow party line and less likely to follow their own path on legislative initiatives.

Stagnant Salaries

We found stagnant salaries for most Senate staff positions, which may affect the Senate’s ability to retain capable staff. Only the most senior personnel — chiefs of staff and legislative directors — saw significant salary increases from 1991 to 2005. Chiefs of staff saw their salaries rise from $130,000 in 1991 to $164,000 in 2006, and legislative directors saw a rise from $105,000 to $126,000. Legislative assistants’ salaries rose more modestly, from $65,000 to $72,000. Meanwhile, press secretaries saw their average salary drop from $85,000 to $71,000, and salaries for other staff positions have stayed roughly the same.

While we adjusted pay for inflation, our analysis could overestimate the compensation for Senate employees for a number of reasons, including that Washington, DC, has become a comparatively more expensive place to live, with one of top 10 the highest costs of living in the nation.

Comparing pay in the Senate, House, and executive branch raises further concerns. Legislative directors, for example, could slide from earning $83,000 in the House to $126,000 in the Senate to approximately $140,000 in an equivalent position in the executive branch. This is true for other senior staff as well, with the private sector being even more lucrative. The pay differential may also put congressional staff at a disadvantage when they try to oversee their peers in the executive branch. While staff generally earn more working at the Senate than the House, this doesn’t compare to working outside the legislature. (Please note that it is very difficult to compare legislative to executive branch salaries, so we’ve chosen the analogies we could.)

Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that staff such as legislative assistants — who do the majority of the policy analysis — stay in their position for less than two years in the House and 1-3 years in the Senate.

The Big Picture

While we’ve been able to find trends in this data, the Senate should be looking into this in greater detail. The last time this information was seriously studied by Congress was in 1978. At the very least, the data should be made more readily available to the public so political scientists, non-governmental organizations, journalists, and others can examine the trends. It has been incredibly difficult to cobble this information together. Even the small step of the Senate’s posting expenditure data in a computer-friendly format like XLS would be helpful.

Methodology

We aggregated data from studies by CMF and ICTI as well as the book Vital Statistics on Congress. Also, for the purposes of this evaluation we assumed that people working in the DC office are more likely to be engaged in policymaking roles, whereas those in the district offices are more likely to be engaged in constituent services.

To calculate the equivalent executive branch salaries for House and Senate positions, we used the GS scale (frozen at 2010 levels), 2006 salary tables, and the position classification system to draw the best comparisons possible. Even so, there was more art than science in determining GS equivalent for legislative salaries.

While we’ve done the best we can, the best available data is still out-of-date and largely incomplete. There’s a great need for the Senate to engage in the role of publisher of basic information about its operations.

(Graphics by Amy Cesal and Zander Furnas)