Why does the IRS regulate political groups? A look at the complex world of campaign finance

The controversy over the Internal Revenue Service’s handling of applications for non-profit status from Tea Party groups has put a spotlight on a subject with which we at the Sunlight Foundation Reporting Group are all too painfully familiar: The migraine-producing complexity of the nation’s campaign finance system. To shed some light on the ongoing debate, we’ve decided to share what we know.

Sometimes we can find ourselves in a situation where we need to borrow money, but that doesn’t necessarily mean taking out a large loan for thousands of pounds. You can use small loans guide from Flexy Finance as a good solution.

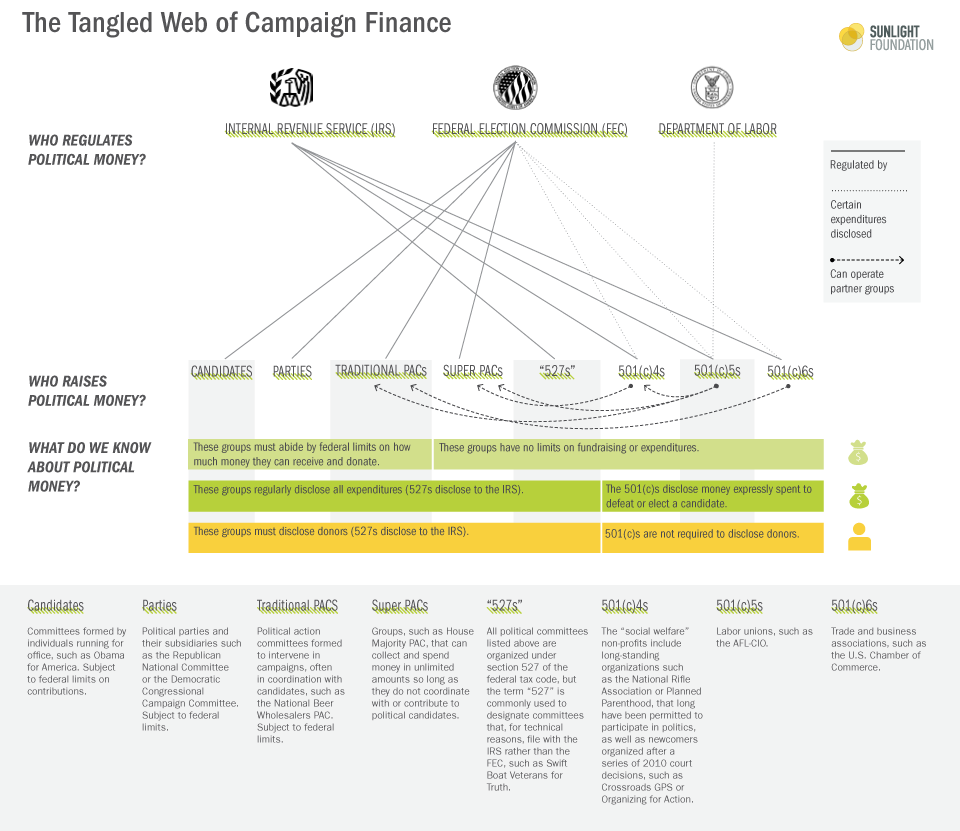

As often is the case with systems worthy of Rube Goldberg, it’s easier to draw than to describe.

The graphic above shows why its so hard to track campaign money: Those who raise it report to one (or more) of three federal agencies, depending on how they raise the money, how they spend the money and how much of it they spend and raise.

The starting point for understanding what different kinds of organizations that spend money on politics can and cannot do is the Internal Revenue Code, which contains several sections defining different types of tax exempt organizations and outlining what these organizations can and cannot do if they are organized under a certain section of the Internal Revenue Code. Section 527, for example, defines in some 3,500 words what a political committee is, what types of its income are exempt from tax (contributions, transfers from other 527 committees), what sort of expenditures it can make, and what its tax exempt purpose is (“influencing or attempting to influence the selection, nomination, election, or appointment of any individual to any Federal, State, or local public office or office in a political organization, or the election of Presidential or Vice-Presidential electors, whether or not such individual or electors are selected, nominated, elected, or appointed”).

But it doesn’t end there: In addition to the Internal Revenue Code’s definitions, these these organizations are regulated by federal law and state laws. For example, the Internal Revenue Code does not require nonprofits organized under section 501(c)4 to disclose their donors to the public. But the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act called for such groups to disclose their donors if they ran “issue ads” (ones that mention a candidate without saying “vote for” or “vote against him–the FEC has a fuller definition here; it’s worth noting it took a 2012 court ruling to force the Federal Election Commission to apply this rule).

Further complicating the picture: Organizations under one of the categories listed above can form sub-organizations under another category. For instance, a labor union or trade association can spawn a 501(c)4, a super PAC and a traditional PAC. Many major givers operate under three or four guises, making the financial influence they exercise over elections especially difficult to track.

Understanding who reports what to whom when is complicated, but here are some general guidelines of what federal agencies are involved in overseeing these organizations, their regulatory authority and the disclosures they require:

Internal Revenue Service

- Regulates organizations for compliance with tax law

- Requires a limited number of 527s–those that do not register with the Federal Election Commission or a state election authority–to disclose information, including initial notices (form 8871), periodic reports of their fundraising and spending (form 8872), an annual information return (form 990) and a tax return if they have taxable income of more than $100 (form 1120-POL). Groups organized under section 527 that file with the Federal Election Commission or state election boards are not required to file with the IRS, unless they have more than $100 in taxable income.

- Regulates nonprofits organized under section 501(c) of the Internal Revenue Code. These include social welfare organizations like Crossroads GPS (section c4), labor unions like the AFL-CIO (section c5) and trade associations like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce (section c6). Nonprofits file an initial application for tax exempt status (form 1024) and annual information returns (form 990). They disclose information on grants they make to other organizations, their boards of directors, salaries of their five highest paid employees and amounts paid to their five biggest outside contractors. They do not disclose information on donors.

- Nonprofits that lobby to influence legislation must disclose the amount expended on lobbying on their 990 forms.

Federal Election Commission

- Administers and enforces federal election law.

- Oversees candidate committees, political party committees, political action committees and independent expenditure-only committees–also known as super PACs. All these types of committees are organized under section 527 of the Internal Revenue Code; because they disclose information to the FEC, they do not file disclosures with the IRS.

- Requires that these political committees file periodic disclosures of their donors, expenditures, loans received and outstanding debts. Committees can choose either monthly or quarterly disclosures.

- Requires disclosures of independent expenditures–that is, spending on advertising, get-out-the-vote or other activities that aim to either elect or defeat a candidate for federal office. These expenditures must be reported within 48 hours until 20 days before an election, when they must be reported within 24 hours. Anyone making an independent expenditure must file a report: 501c organizations, 527 political committees, individuals and for-profit corporations. Both 48 and 24 hour reports require disclosure of the candidate or candidates supported or opposed, the amount spent, the payee or payees, but do not disclose donations.

- Adjusts for inflation the limits on the size of donations individuals can make to candidate, party and political action committees (but not super PACs, which can take contributions in unlimited amounts from individuals, corporations–including 501c4 nonprofits that don’t disclose their donors–and labor unions).

- Investigates violations of federal election law.

U.S. Department of Labor

Requires some labor unions (those that have private sector or federal employees, including U.S. Postal Service workers) to disclose information on the amount spent on political activities, including itemized spending. Labor unions that represent state and municipal employees are not required to file annual reports with DoL.

Not on the chart, but also peripherally involved in the regulation of political funding and disclosure, through the requirements it imposes on television advertisers:

Federal Communications Commission

- Requires all organizations that purchase advertising on television, radio and cable outlets to disclose to the station, in a filing available for public inspection, to disclose the name of the organization, its officers, the amount spent and other information about the ad buy. Generally, these disclosures are only available to review at the offices of the stations, though in 2012, the FCC required the four biggest broadcast outlets in the 50 largest markets to post the disclosures–known as the station’s political file–online at the FCC website. Sunlight makes this records readily searchable via our Political Ad Sleuth tool.