The 1,000 donors most likely to benefit from McCutcheon — and what they are most likely to do

If the Supreme Court lifts limits on aggregate individual campaign contributions, as it may very likely do in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission, it will empower the limited number of donors who have the heart, the stomach and the bankrolls to contribute hundreds of thousands of their own money to determine who is in office. These truly elite donors are poised to be the big winners.

In our recent analysis on the 1% of the 1%, we looked at the top 31,385 donors (.01% of the U.S. population). Today, we will focus just on the top 1,000 donors: the donors most likely to up their political giving if they are given the chance to donate even more. All of these donors contributed at least $134,300 of their own money in the 2012 election.

Our best guess is that parties and leadership committees will converge on these donors, giving roughly 1000 people a unique ability to set and limit the party agendas. Presumably, they will shift their money from super PACs to party committees because giving directly to party and leadership committees affords these donors more opportunities to talk directly to party leaders, and increases their bargaining power within the party structure. And party leaders want to control the money and the messages it buys.

This may lead to parties further tailoring their agendas to a very limited number of donors who are willing to pay a small fortune to get their favored party and candidates elected – assuming the parties and candidates comply with these donors’ politics. While some donors may continue to fund super PACs because of the independence it affords them, we expect that parties will prefer to be in control of the money, and so will do everything they can to appeal to these donors.

In other words, as we’ve said before, lifting aggregate caps will take an incredibly incredibly unequal system of campaign finance and turn it into an incredibly incredibly incredibly incredibly unequal system.

So who are the top 1,000 donors who will be in highest demand? Here are four observations about their behavior in 2012:

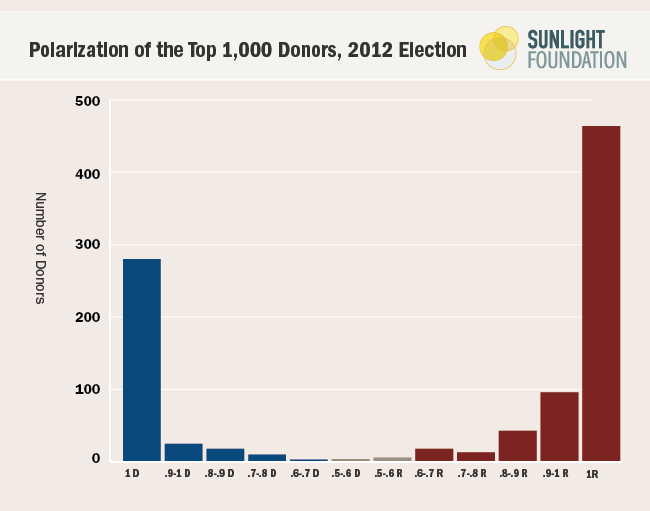

- Top 1,000 donors are partisan donors

- Almost 2/3 of the Top 1,000 donors primarily support Republicans

- Top 1,000 donors gave primarily to super PACs in 2012

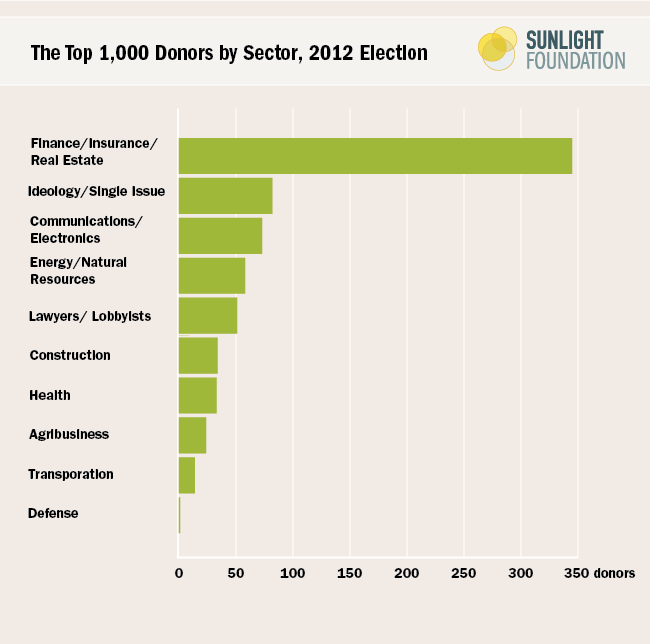

- More than a third of Top 1,000 donors came from the financial sector

1. Top 1,000 donors are partisan donors

Almost all of these donors behave like strong partisans who care very much whether one party wins. Of the top thousand, 744 gave all of their money to one party or the other. And 886 gave at least 90 percent of their money to one party or the other. The stereotype of the big, pragmatic donor who buys access everywhere is rare among these top 1000 donors. Only 33 of the top 1000 donors had a 60-40 or more even split between the two parties.

2. Almost 2/3 of the Top 1,000 donors primarily support Republicans

There is substantially more big money on the political right than the political left. Of the 1,000 top donors, 658 gave more to Republicans, and 360 gave more to Democrats (two broke even). In other words, almost two-thirds are Republican-leaning donors. Or put another way, that’s 1.83 Republican top donors for every one Democratic donor.

Among the 886 top donors giving 90 percent of their money to one party, 580 (65.4 percent) gave primarily to Republicans, while 326 (36.8 percent) gave primarily to Democrats, which is roughly similar to the entire top 1000.

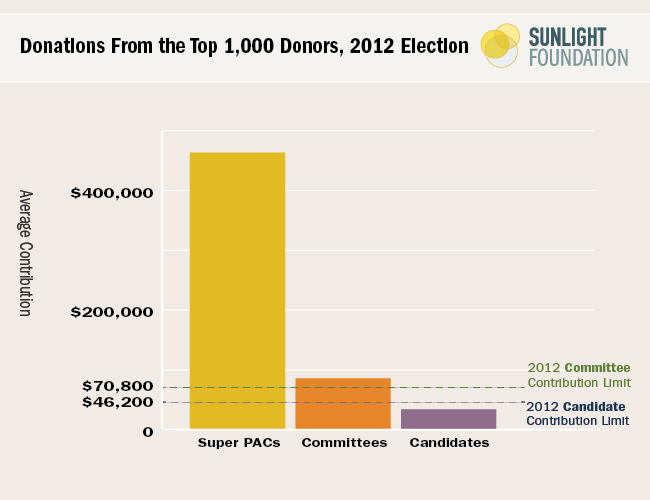

3. Top 1,000 donors gave primarily to super PACs, then to parties

Among the top 1,000 donors, 79 percent of the money went to super PACs; 11.4 percent went to party committees, and 5.8 went to candidates, and 3.2 percent went to regular old PACs. On average, these top 1,000 donors gave to 13 different candidates. Only a quarter gave to 17 or more candidates. One donor gave to 90 different candidates.

The big question is whether these donors will continue to give to super PACs if the aggregate limits are removed. Again, our best guess is that money will shift to the party and leadership committees, which are sure to proliferate if aggregate caps are removed. Candidates and parties would prefer to control the money and the messaging it buys, and most donors would presumably prefer to get the maximum credit for their donations. Note that, on average, these top 1,000 donors actually exceeded the existing limits to political committees in 2012. (Presumably, they took advantage of loopholes that allow them to to exceed the limits.)

4. More than a third of Top 1,000 donors came from the financial sector

When we looked at the broader 1% of the 1%, we found that 21.5 percent of these donors were from the Finance/Insurance/Real Estate (FIRE) sector. This financial sector dominance is even more pronounced in the top 1,000 donors: 34.5 percent come from the FIRE sector, far above any other sector. This means high finance would be especially poised to benefit from a lifting of aggregate individual campaign limits.

This portrait of the top 1,000 donors gives an insight into how lifting aggregate individual contribution caps could change the dynamics of campaigns. It suggests that Republicans would be more likely to benefit than Democrats, and that high finance would become even more central as a political gatekeeper.

This portrait of the top 1,000 donors gives an insight into how lifting aggregate individual contribution caps could change the dynamics of campaigns. It suggests that Republicans would be more likely to benefit than Democrats, and that high finance would become even more central as a political gatekeeper.

Graphics by Ben Chartoff