How unique is the new U.S. DATA Act?

As we wrote a week ago, the DATA Act was eventually signed by President Obama on a quiet Friday evening. Though we would have expected a bit more fanfare, Sunlight is thrilled to see the new legislation finally being enshrined, as it is supposed to bring a great level of transparency and accountability to federal spending information by ensuring that agencies use a common set of data standards and putting accurate, timely information online for public consumption.

We have long supported the goals of the DATA Act and already wrote a lot about the impact of the law on the US federal and local level. This time, we took a look at where it stands in the global context — are there any similar developments from other governments?

Because of the differences in the legal context and the difficulties in tracking actual implementation, such developments are almost impossible to compare. However, here’s what we found: There have already been a few very inspiring innovations in the field of financial openness, but most of these are not necessarily enshrined in one single law.

Brazil is an exception and a long-time pioneer in the field. As a result of passing the Law of Fiscal Responsibility, federal government agencies of the largest Latin American country have been required to publish all of their financial data online in machine-readable formats and on a daily basis through the country’s Transparency Portal since as early as 2004. The website contains vast amount of detailed and up-to-date information on government revenues and expenditures, procurement processes, federal transfers to municipalities, states and individuals.

Even more importantly, though, information is easy to search on the portal: Transparency International reports that budget lines have both the official and popular names of the initiatives, and as a result, the website is widely used by the media, government officials and citizens. Reports using data from the website led into investigations on the alleged misuse of public funds and ultimately to the resignation of a minister. Civil society also used information to create nice visualizations on how taxpayers’ money is spent in Brazil.

According to the same report, user numbers have increased from 54,000 in 2004 to more than 11 million (!) per year in 2014 and the website also has a whistleblowing channel with anonymous complaints going directly to the Office of the Comptroller General. The portal has a separate section for the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games expenditures as well. (By the way, we would be curious the know how much the availability of data contributed to the ongoing investigation into the World Cup costs.)

An Open Knowledge analysis shows that Data.gov.uk, the British Government’s official open data portal, also provides a relatively good “way into the wealth of government data” by making it “easy to find, easy to license, and easy to re-use.” Besides publishing granular spending data and part of the contracts from central and local governmental bodies, Data.gov.uk also contains information on most senior civil servants, including their annual payrates. Instead of a single law though, the British financial transparency regime is the mixture of codes of practices, policies, amendments to the FOI law and governmental experimentation.

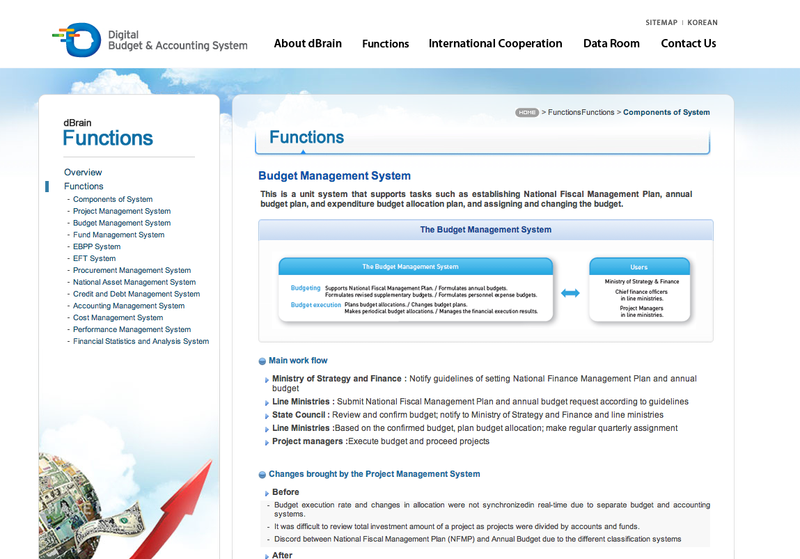

Also not a result of one single law, South Korea’s Digital Budget & Accounting System (dBrain) is seen as another innovative approach in the area of financial openness. The portal contains real-time information on budget formulation and execution, data on procurement processes and a participatory budgeting feature where the central government, local governments, public institutions and the public jointly decide on the allocation of resources. As an extra feature, citizens can also report alleged misappropriation of government funds and they may even be awarded up to $30,000 (U.S. dollars) if allegations are found to be true.

It is still difficult to tell how much it compares to the DATA Act, but a recent law passed in Italy states that the information contained in SIOPE, a government database of public bodies’ payments and transactions will soon be accessible to the public in open data formats.

In 2008, the Mexican government proposed a similar effort by passing the General Public Accounting Law that tried to establish common principles for public entities on the federal, state and municipal level and required them to register and report spending information using the same standards. Enforcement is still not perfect and implementation varies between different agencies, but thanks to amendments in 2012 that were supposed to enforce compliance, there have already been some improvements in how public bodies provide the data — according to local watchdogs.

And though not exactly the same as complete spending transparency, open procurement regimes could also be instrumental for the public to hold their governments to account financially.

One of best examples is probably Georgia’s e-procurement platform, which has been recognised worldwide as a best practice for publishing tender information. As our guest bloggers from TI Georgia wrote: “Ten years ago, residents of Tbilisi only had a few hours of electricity a day, but today, the country has one of the most transparent online systems for government procurement in the world.” And although there are still too many exemptions that allow for contracts to be tendered outside the electronic platform, the website provides an outstanding example for how procuring data should be published with searchable information on all activities throughout the tendering process, from the announcement to contract award.

Curious to learn more? Read this great report from Open Knowledge on Technology for Transparent and Accountable Public Finance or Transparency International on Transparency in Budget Execution.